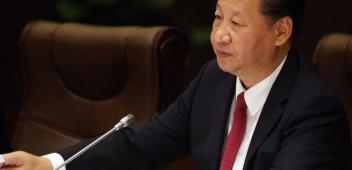

Xi Jinping reels in his tech titans

Private enterprise created China’s vaunted digital economy. But Big Brother is always in charge. Originally published in the Australian Financial Review.

For two countries daggers drawn on everything from the South China Sea to new technologies, the US and China had an instructive meeting of minds this month.

Days after Didi Global’s US$4.4 billion listing in New York in early July, Beijing launched a national security investigation into the homegrown ride-hailing giant, instantly cratering its share price.

Within weeks, Beijing had raided the company and stationed police, intelligence, tax and cyber officers inside its offices as part of a national security review of its collection and handling of data.

Yes, you read that right. Beijing hasn’t just put regulators inside the Uber of China. It has also placed Ministry of State Security officers there, the first time a permanent intelligence presence has been stationed inside a local tech company, or at least announced so publicly.

In Washington, meanwhile, China hawks such as Florida Senator Marco Rubio have long been railing about the US allowing Chinese companies like Didi to access its capital markets.

Even if the Didi stock rebounds, Rubio said after the initially successful listing that “unaccountable” Chinese companies had placed “the investments of retirees at risk and funnelling desperately needed US dollars into Beijing.”

In the post-9/11 world, the war-on-terror was the key organising principle for policymakers. Now, every issue in the US and China, and Australia, is viewed through the prism of superpower competition.

In most respects, China was early to the game of high-tech decoupling, constructing its Internet inside the protective Great Firewall from the late 1990s onwards.

The next time you hear a Chinese official complain about the banning of Huawei from western 5G networks, remind them that Beijing has systematically excluded western Internet giants, like Google and Facebook, from its own market over more than a decade.

In other words, decoupling started in China. If recent western policies against China look harsh by comparison, that’s only because democracies like the US, Australia and the UK and so forth are playing catch-up.

But with the crackdown on Didi, and the reining of the country’s tech behemoths, Alibaba and Tencent, in recent months, it is now Beijing that is engaging in its own house-cleaning exercise.

If, as the saying goes, your data knows more about you than you know about yourself, the only surprising thing about the crackdown on big tech in China is that it took so long.

Didi has 377 million daily uses and has amassed a treasure trove of data about street mapping and consumer mobility. As late as the 1990s, old-fashioned city maps in China were restricted on national security grounds.

Superpower politics has naturally taken front stage in the crackdown, for obvious reasons. Beijing doesn’t want US regulators to have any power over Chinese tech companies and their valuable data.

Equally, Beijing has made a priority of building its own capital markets in recent years, building up Shanghai and Shenzhen and bolstering Hong Kong. To that end, it doesn’t want its best companies raising money in New York anymore.

Still, for all its global dimensions, the big tech crackdown in China can only be properly understood in the domestic political context.

There are no big privately owned Chinese banks, oil companies and telco and power providers, because legacy state-owned enterprises have been allowed to keep control of those sectors.

When the Internet came along in the 1990s, however, there were no legacy companies, and entrepreneurs rushed to fill the gap. Freed from local and foreign competition, the Chinese Internet entered what the local media calls a period of “barbaric growth.”

At some point in recent years, Xi Jinping and the country’s national security hawks decided they had grown enough, and needed to be reined in.

In Xi Jinping’s China, more so than his predecessors, there is a simple benchmark by which to judge private companies and entrepreneurs. They either make the state stronger, or they threaten to diminish its power.

In the case of Chinese big tech, they have been favoured for years, as they were central to the modernisation of the local economy and financial and consumer markets.

A cocktail of factors tipped the balance of forces against them.

Their control of data, power over the media, defiance of regulators, the ability to lend consumers money, thus undermining the state banks, and perhaps most of all, the cult of personality surrounding their charismatic leaders, like Alibaba’s Jack Ma, all helped turn the tide against them.

Once their friend and protector, Xi changed his mind and decided the companies needed to be taught a lesson about the bigger national security issues in play.

Chinese tech companies are not about to shut down. But their wealthy bosses have been rudely reminded about who’s in charge, and it isn’t them, no matter how many billions they’ve made.

The centralised big data analytics that the tech titans have at their fingertips, after all, isn’t a tool to allow free markets to prosper.

In Xi’s hands, it is a device to bring markets more firmly under control, and strengthen the state and the ruling party for the battles ahead, at home and abroad.