The United Nations emergency relief coordinator Martin Griffiths has warned in recent months that Myanmar faces a worsening humanitarian crisis, including mass displacement and a dire need for food and aid for civilians. Talk of civil war has even escaped the lips of usually cautious officials.

Much of the world continues to look to the Association of Southeast Asean Nations to resolve the tensions in Myanmar following the February 2021 coup. However, ASEAN members remain divided on the role the grouping should play since the military takeover. Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen drew criticism this month for meeting Myanmar’s military ruler Min Aung Hlaing in Naypyidaw after ASEAN had taken the unprecedented step to exclude the general from its summit last October. Hun Sen also claimed last week that Myanmar would be welcome at ASEAN should it make progress on a peace plan, only for Malaysia to quickly reject the idea.

Indonesia has been the most vocal member of the regional bloc to openly criticise the coup. Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei have similarly expressed concern. Yet a number of ASEAN countries, including Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines, initially described the coup as an internal issue for Myanmar. The Philippines has modulated its position in the year since the military takeover and called for the immediate release of imprisoned former state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, while Thailand has also recognised the ramifications as Myanmar’s tensions spill over its shared border.

The lack of significant progress during the last year will inspire little confidence about ASEAN’s ability to resolve Myanmar’s challenges even when faced with spiralling regional dangers.

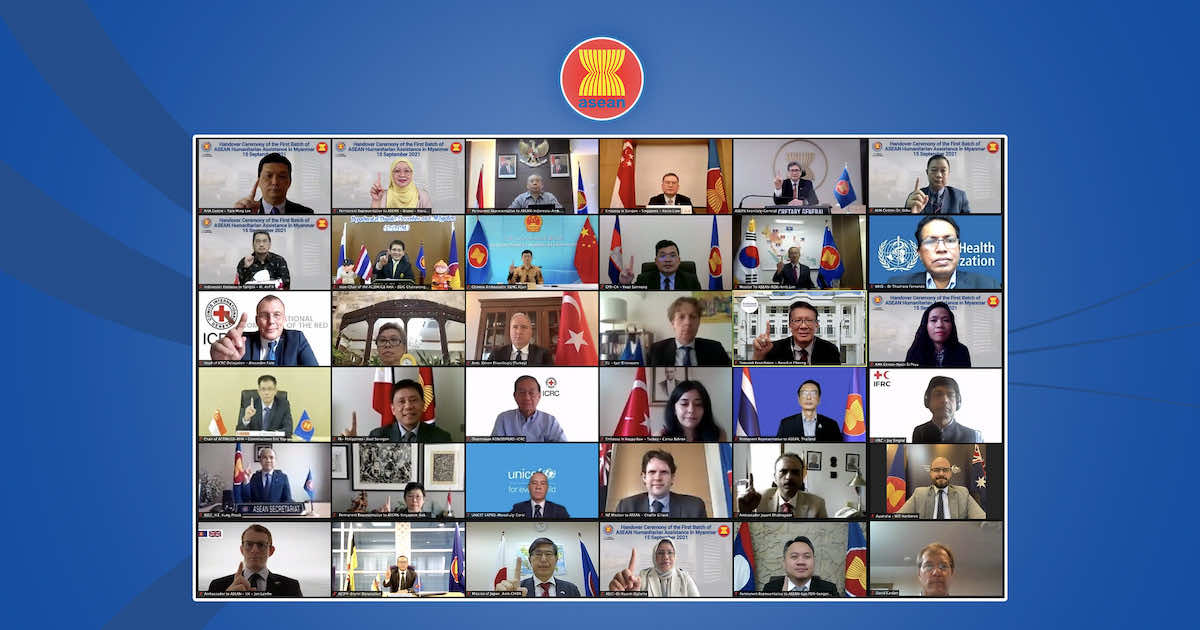

ASEAN leaders have pursued the so-called “five-point consensus” on Myanmar developed at a special regional summit in April 2021, which included the provision of humanitarian aid, promoting and facilitating dialogue between different actors, ending violence and appointing a special envoy to visit Myanmar, eventually settling on Brunei’s Erywan Yusof and subsequently Cambodia’s Prak Sokhonn. The gravity of the situation compelled ASEAN to take urgent steps despite its longstanding emphasis on non-interference in the internal matters of member states.

Still, there has been little progress. The appointment of the special envoy to Myanmar took months – with Erywan Yusof only confirmed in the job in August – and the junta has continued to block humanitarian aid to those in desperate need. Covid-19 has compounded the problems and close observers have warned the objectives of the five-point consensus could take more than two years to achieve. The newly appointed UN special envoy for Myanmar Noeleen Heyzer has said that fighting in the country needs to end before the five-point consensus can be implemented.

ASEAN has sent some important signals. The decision to exclude Min Aung Hlaing from the ASEAN summit in October amounts to the most severe sanction the grouping has taken against Naypyidaw. It was likely motivated by the organisation’s interests to remain relevant in the regional diplomatic theatre. Allowing Myanmar to be represented in leaders’ meetings would only have further hampered the organisation’s legitimacy – beyond criticism that the emphasis on sovereignty undermined ASEAN’s credibility and standing as a regional bloc. As analysts have noted, the ASEAN Charter adopted in 2007 does not provide guidelines on how to respond to a coup in a member state that could result in regional instability.

But there seems little prospect of resolving the friction within the bloc about how to deal with the junta. Cambodia has taken over the ASEAN chair in 2022 under a rotating arrangement and Hun Sen’s decision to visit Naypyidaw could also be construed as the grouping legitimising the coup.

Instead, the steps will be incremental. The ASEAN secretariat is organising an international donor conference for Myanmar at Thailand’s suggestion. ASEAN is also seeking to mobilise support to fight the Covid-19 pandemic, with Myanmar’s hospitals struggling with lack of medical supplies and intensive care capacity. Sokhonn and his team are also planning a visit.

But the lack of significant progress during the last year will inspire little confidence about ASEAN’s ability to resolve Myanmar’s challenges even when faced with spiralling regional dangers, including the greater displacement of refugees, greater incidence of human trafficking and worsening transnational crime and the resultant economic costs. For ASEAN, the crisis could prove an existential one.