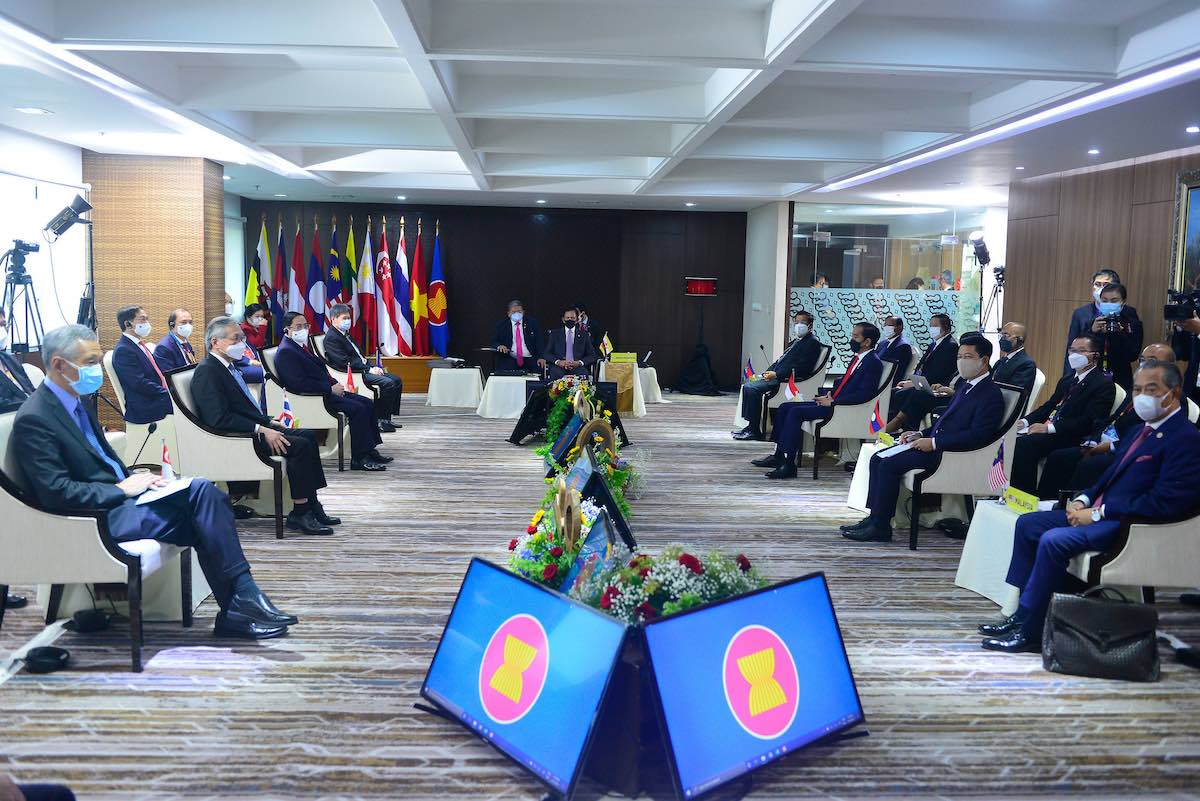

It has been a month since the ASEAN Leaders met with Myanmar junta Leader Min Aung Hlaing on 24 April in Jakarta to discuss the situation in Myanmar. The meeting itself and the outcome of it – the Five-Point Consensus – has been applauded by some as a rare win for ASEAN, given its limitations in addressing crises, and derided by others as legitimising the coup and strengthening the hand of the military.

Any optimism on the “ASEAN way” forward, however, is fast evaporating with the absence of a clear implementation plan for the five-point-consensus, the delayed announcement and specific objectives of the ASEAN envoy, the continued violence against civilians by the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military forces), and the displacement of thousands of people in the border states. Critics of ASEAN have called out the regional grouping for not condemning the violence of the Tatmadaw and allowing the State Administrative Council (SAC) to buy time to consolidate power.

So far, dialogue partners including Australia and the United States have rallied around the five-point-consensus, and apart from targeted sanctions, they have been relatively constrained in their policy responses to the coup. This is in part a recognition of the limited leverage they have over the junta and that despite its limitations, ASEAN is the only and best option available towards resolving the crisis in Myanmar. While the five-point consensus has its shortcomings, it provided a path forward for ASEAN to address the political and humanitarian crisis in the country. Prior to this, the international community did not have many options to begin with.

As one expert on Myanmar has pointed out:

Someone has to talk to the coup leaders about how they may get out of the hole they have dug for themselves, and there aren’t many who are both willing and able to take on that thankless task.

The appointment of an ASEAN envoy who would help broker dialogue among the concerned parties is a key component of the five-point consensus. Several names have been suggested, including former Indonesian foreign minister Hassan Wirajuda and former Prime Minister of Singapore Goh Chok Tong. As the Chair of ASEAN, however, Brunei has yet to name the envoy. It is likely that this person would have to be “approved” by Min Aung Hlaing before being named publicly.

The SAC is unlikely to enter into any mediation process if they could not get what they want – i.e., preservation of their central role in Burmese politics. As unpalatable as it might sound to the National Unity Government (NUG), protestors from the civil disobedience movement, or the international community, the ASEAN envoy would likely have to accord some degree of legitimacy to the SAC in order to keep them engaged. He or she will also have to recognise the differing interests and political motivations of the SAC, NUG and the ethnic armed groups (EAGs).

Regardless of who the ASEAN envoy is, the appointment should also not be seen as a silver bullet. The junta has already rejected any visit by the ASEAN envoy, stating that it is “prioritising the stability and security of the country”.

ASEAN has dangled the carrots to bring General Min Aung Hlaing to the table. At some stage, it needs to signal to him and the junta that it is prepared to wield its sticks.

While ASEAN may be adopting a tactical approach in moving slowly and not risking the small gains achieved so far, it is taking a huge gamble in letting the junta dictate the pace of progress. Pressure for ASEAN and external powers to do more will mount if the violence continues and the death toll rises. ASEAN will find it hard to remain silent if the Tatmadaw is given impunity for their acts of aggression against unarmed civilians, including children.

Most of the ASEAN leaders – particularly Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand – understand the stakes are high for ASEAN and that the recalcitrant Tatmadaw will affect the grouping’s reputation and relationship with its partners. At this juncture, ASEAN’s preference would be for minimal interventions from external powers, which will in turn increase its strategic options vis-à-vis the junta. However, that strategic space will get smaller unless ASEAN quickly produces a clear action plan for the five-point-consensus, especially the cessation of violence.

The question is whether ASEAN has any real leverage over the junta.

Two member states – Singapore and Thailand – have clear economic and financial leverage, but they are unlikely to exercise it. ASEAN has some leverage in terms of providing humanitarian assistance through the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance (AHA Centre), and this is one of the five points. Finally, ASEAN may have some political leverage with the suspension of Myanmar as a member. The benefits of ASEAN membership have not been lost on the junta, and while they may be prepared for economic sanctions from the Western world, the last thing they want is for the country to return to being a reclusive state.

ASEAN has dangled the carrots to bring General Min Aung Hlaing to the table. At some stage, it needs to signal to him and the junta that it is prepared to wield its sticks if Myanmar is not acting as a “member of the family”.

The release of some political prisoners and foreigners out of the more than 3000 detained is low-hanging fruit which ASEAN should strongly encourage, even though it was not part of the five-point-consensus. This should be done at all levels – regionally, bilaterally and through the ASEAN envoy (once appointed). The release would attract some goodwill and humanitarian assistance from the international community, which could be channelled through the AHA Centre to the border areas and communities where aid and supplies are badly needed.

The five-point-consensus should not be taken for granted. Getting to this point has involved copious amounts of quiet diplomacy and the dedication of ASEAN leaders to the issue. ASEAN needs to make clear to the SAC that they are not getting a free ride. It should be prepared to exercise whatever leverage it has over the junta to end the violence against Myanmar’s people and to contain the risks of regional instability.