Whether Australia leases, buys or builds nuclear-fuelled submarines, it will be the first non-nuclear state to do so. The recent announcement of AUKUS – the Trilateral Agreement between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States – to procure this technology brings into focus the question of the continued health of Australia’s nuclear “grand bargain”.

The grand bargain, established in the late 1970s in the wake of the Ranger Uranium Inquiry, and enunciated by then Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, determined that Australia while abjuring the development of a full civil nuclear industry, would meet its obligations as a non-nuclear weapons state (NNWS) member of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) by only exporting uranium subject to strict International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards and conditioned by the NPT status of recipient countries.

This approach was based on a commitment to ensure that the desire to reap the potential economic benefits of exporting uranium were balanced by the country’s strategic and normative interests in limiting nuclear proliferation. In subsequent decades, Australia leveraged this commitment to strict export controls to extend the capacity of the non-proliferation regime through the development of supplementary agreements and institutions such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT).

For Australia, one of its greatest considerations must be balancing the risk of an HEU naval nuclear reactor with its commitment to the non-proliferation regime.

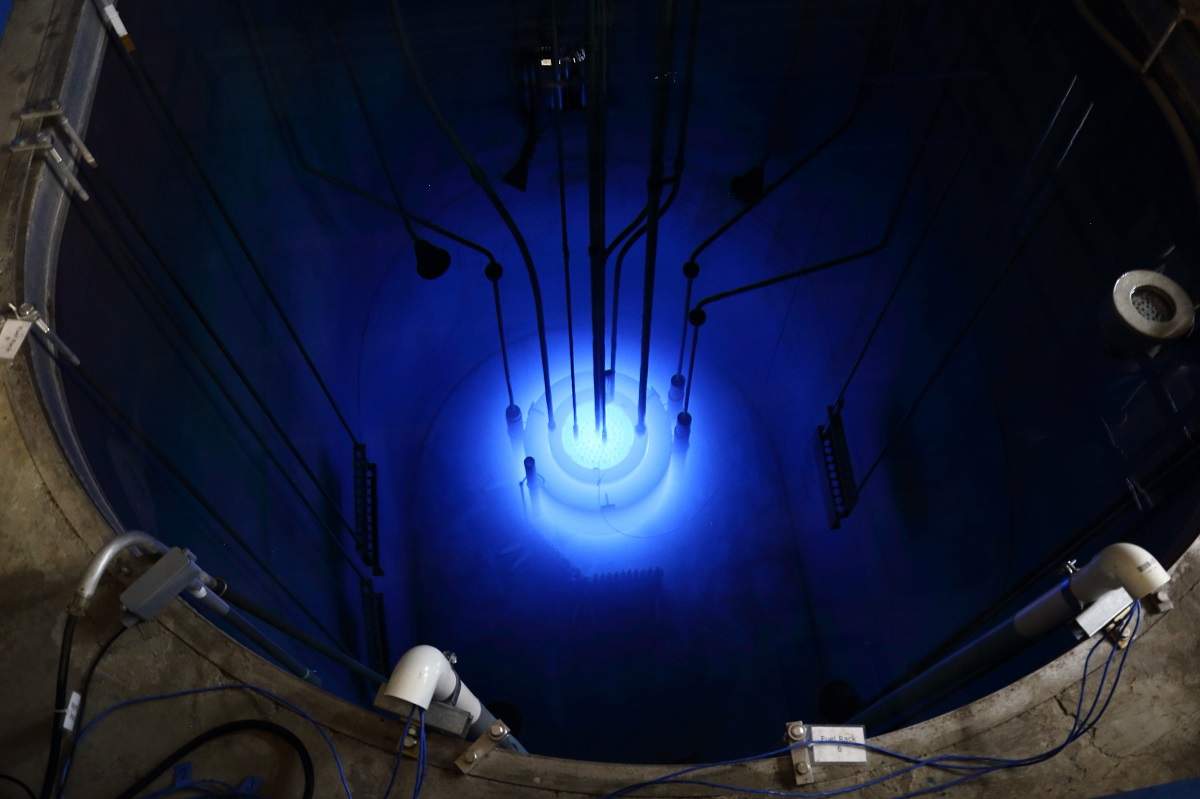

There is no doubt that nuclear-fuelled submarines are the most lethal and revolutionary advances in underwater weaponry. The increase in performance, deployment and speed without the need to refuel cannot be overstated, but this does come with risk to Australia’s established nuclear policy and status. Highly enriched uranium (HEU) naval reactors are currently employed across four navies, putting Australia in line with its trilateral partners, but also with Russia and India. Most existing HEU naval nuclear reactors use weapons-grade uranium (enriched to over 90 per cent) or uranium enriched to at least 20 per cent U-235. For context, a typical civilian nuclear power reactor uses about 3.5 per cent enriched uranium.

For Australia, one of its greatest considerations must be balancing the risk of an HEU naval nuclear reactor with its commitment to the non-proliferation regime. Australia must initiate and adhere to additional strengthening of the production, use and disposal of HEU under the IAEA and NPT safeguards if HEU reactors will be employed in the new fleet. Australia has a rich history in influencing and shaping state behaviour within the nuclear regime and this new agreement could be the cornerstone for Australia to lead in addressing the proliferation and disarmament issues raised by the nuclear naval reactor.

The naval reactor has long been seen as a loophole to the NPT and IAEA safeguards whereby a NNWS could divert materials from naval reactors and potentially use that material for weapons production. There is obviously a clear difference here with intent of purpose for Australia with the new fleet. Nonetheless, as James Acton has noted, the risk remains that Australia’s potential exploitation of this loophole to avoid IAEA oversight of HEU may be a precedent exploited by others. It would be an irony of some order of magnitude given Australia’s long record as a champion of IAEA safeguards and guardianship if its pursuit of this strategic capability was in fact to make it easier for others to avoid IAEA scrutiny.

Australia could be a leading NNWS with sensitive nuclear technology and be responsible for closing this loophole, thereby staying true to its commitment of non-proliferation and disarmament. As Thomas E. Shea, among others, proposed in a solution to this problem in 2017, Australia could and should be at the forefront of examining this scenario through the NPT. In 2017, no NNWS was on the verge of acquiring or building nuclear-powered submarines, however clarification was needed then, as it is now. Of the points for consideration in Shea’s proposal, Australia should have transparency regarding the application of IAEA safeguards; have strict verification methods for the amounts of enriched uranium and its use; and pledge unambiguous assurances that a naval nuclear reactor is just that and not the precursor to anything more. This would be a watershed moment for Australia as the vanguard and model on which to base any other NNWS considering a sovereign or shared nuclear-fuelled vessel.

Australia’s place of influence in the nuclear regime must remain a key driver in maintaining Australia’s nuclear grand bargain.

Indeed, if these measures were enacted through the nuclear regime, Australia could have nuclear-fuelled submarines while maintaining its position on non-proliferation, dismissing any notion of “floating Chernobyls” as alarmist and factual fallacy. Australia holds a strong position with exemplary credentials in the nuclear realm, and its past commitment to the nuclear non-proliferation regime – with abundant uranium reserves and export potential, and now with the capability of being the first NNWS with this type of technology – gives it further leverage to influence the behaviour of other states.

A question, however, remains over the longevity of Australia’s grand bargain. Advocating for capability over concept leaves Australia in a precarious position within the nuclear regime and prescribes a very particular strategic consideration. Ceding some strategic and defensive sovereignty to the United States in acquiring dual nuclear-use technology undeniably for military use, leaves many unanswered questions. For starters, where will the fuel come from? Will Australia eventually be required to process and enrich uranium?

This opens Australia up to scrutiny and it must be prepared for its position as a nuclear “white knight” in the non-proliferation regime to come under the microscope. Over the next 18 months, these questions in conjunction with Australia’s place of influence in the nuclear regime must remain a key driver in maintaining Australia’s nuclear grand bargain.

Viewed in the context of Australia’s historical engagement with nuclear issues, the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines and the potential risks they imply from a non-proliferation perspective should not be complacently bargained away.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not those of the Department of Defence.