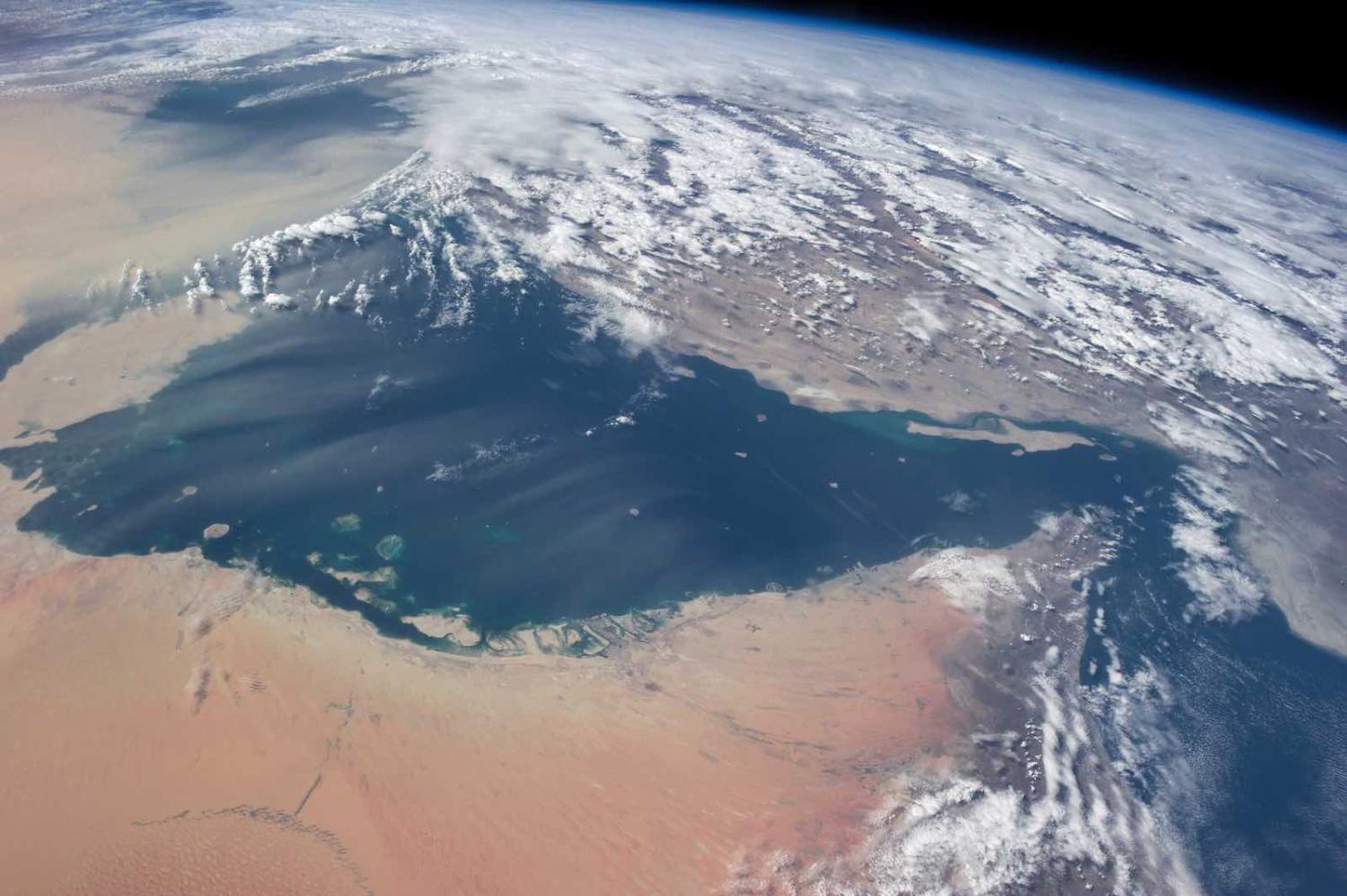

Prime Minister Scott Morrison was at pains last week to emphasise the “modest and time-limited” nature of Australia’s contribution to the new US-led maritime security mission in the Strait of Hormuz known as the International Maritime Security Construct’ (IMSC). He batted away suggestions that this could embroil Australia in the escalating tensions between the US and Iran, insisting that the mission is “all about de-escalating tensions” and “not related to any other matters that are the subject of a lot of attention in that region”.

“They’re completely separate issues,” Morrison said, and to conflate them would be “ill-informed”.

In operational terms, Australia’s contribution is clear and discrete: a P-8A Poseidon maritime surveillance aircraft for one month before the end of 2019, a frigate for six months in early 2020 and Australian Defence Force personnel to join the mission headquarters in Bahrain. This amounts to little more than a crafty reallocation of resources from our existing contributions to international maritime security operations in the Gulf.

But on a political level, Australia is entering muddy waters. Morrison’s announcement has prompted questions about the larger political resonance and long-term consequences of this decision – and rightfully so. Given our long history of following the US into wars in the Middle East, and in the context of brewing hostilities between Washington and Tehran, Morrison’s announcement warrants close scrutiny.

First, there is reason to doubt the government’s insistence that the decision to join the IMSC is “completely separate” from our broader position vis-à-vis Iran. Australian leaders might like to think that this mission can be “tightly framed” around the issue of freedom of shipping, but the IMSC is not a “peacekeeping” mission, and it cannot be understood outside of the escalating tensions between Iran and the US.

Morrison cited the government’s longstanding concerns regarding “destabilising behaviour” and “incidents involving shipping in the Strait of Hormuz”, but has so far completely overlooked President Donald Trump’s own destabilising behaviour, which remains the primary cause of the fissures in US relations with Iran and the deteriorating security situation in Hormuz. Since his decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in May 2018 – a deal that Australia still supports – Trump has unilaterally imposed sanctions on Iran and steadily increased his rhetoric against the Islamic Republic, leading many to suggest that he is posturing for war. Backed by hawkish advisors who have openly called for regime change, many commentators view the tensions in the Gulf as the result of US provocations.

In this context, the build-up of a US-led multinational coalition will likely further escalate tensions between the two countries. (At the very least, it won’t de-escalate them.) A number of potential partners of the IMSC have refused to join on this basis, and Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif has warned that “adding foreign naval fleets in this narrow and crowded tinderbox only increases the risk of combustion.” That is difficult to square with Defence Minister Reynolds’ claim that “de-escalation” is Australia’s “core interest in this mission.”

Second, it is doubtful whether the “international coalition” we have joined is all that international.

Given the escalating tensions between Trump and Iran and the unpredictability of American policy, Australia should think carefully before waiving our independence and lining up behind the US yet again.

So far only Bahrain and the UK – which failed to assemble a European coalition and then decided to join the US one – have signed up. Trump’s unilateral approach on Iran has made coalition-building around this mission difficult. Germany refused to join the US-led mission, indicating scepticism over whether the IMSC will promote stability and emphasising the importance of renewed diplomatic efforts. European countries initially expressed support for a European-led mission in the Strait of Hormuz but all have refused to join the American-led one.

This is telling. Stabilising the situation in the Strait of Hormuz and preserving freedom of shipping is clearly a global priority. But is joining the IMSC the best way for Australia to contribute to that objective?

It is important for Australia to remain committed to the US alliance (regardless of who’s in the White House), and in this instance the commitment does not come at major cost. Australia has a genuine economic interest in safeguarding global oil supply through the Strait, and it would be too quick to read the decision to join the IMSC as an indication that Australia would join the US in military action against Iran should things escalate. The decision to put Australian troops under US command in the current circumstances raises timeworn questions about the ability or willingness of Australian leaders to say “no” to Washington – especially when so many other countries have.

In the past, Australia has maintained good diplomatic relations with Iran (even when the US hasn’t) and has played a constructive role in non-proliferation and disarmament initiatives such as negotiations involving Israel. But there are signs that this independent stance is changing. Last year Morrison ordered a review of Iran policy, and despite maintaining support for the JCPOA, has expressed reservations about “what’s not in the agreement”. Australia continues to apply sanctions under UNSC Resolution 2231 and some “autonomous sanctions” on the export of arms and related materials. The PM has indicated that the prospect of additional sanctions is under “active review”.

Morrison appears to be half-in, half-out – supporting the IMSC, but not committing to all elements of the US “maximum pressure” campaign. For how long will Morrison be able to toe this line and insist that the IMSC is “separate” to wider developments in the region? It’s hard to justify now, let alone if the security situation deteriorates. As the Prime Minister himself acknowledged, it’s difficult at this point to see how things will end: “I mean, we can’t predict the future.”

But we do know the past. Australia has a long history of falling behind US foreign policy in the Middle East. Given the escalating tensions between Trump and Iran and the unpredictability of American policy, Australia should think carefully before waiving our independence and lining up behind the US yet again.