The national dignity conferred by true independence warrants the best possible constitutional model for an Australian republic. But one of the main stumbling blocks to Australia moving from constitutional monarchy is the uncertainty around what model should replace it.

While serious discussion of alternatives is welcome, it’s disappointing that the model recently proposed by the Australian Republic Movement (ARM), the leading voice for constitutional change in Australia, is premised more on polling than rigorous considerations of national governance, not least in foreign policy and national security.

The “Australian Choice Model” proposes a popularly elected head of state, serving up to two 5-year terms, with candidates nominated by Australian parliaments. Most importantly, the head of state’s substantive powers would largely mirror those of the Governor-General.

As former prime minister Paul Keating and constitutional law expert Professor Anne Twomey have pointed out, the essential problem with the ARM’s proposed model is that it would create “rival power centres”. As Twomey says, “[i]f you have an elected head of state the biggest concern is they have a mandate from the people and that mandate from a directly elected head of state would override the mandate of the prime minister who is not directly elected by the people.”

Ambiguity or, worse, outright discrepancy between prime minister and head of state tempts exploitation by adversaries and diminishes trust from allies and friends.

The reason the current model functions well enough is precisely because the Governor-General’s mandate is the sovereign’s appointment on the advice of the Prime Minister. While a shift to a republic is an important change for Australia’s identity and full independence, a minimum of substantive change is preferrable to maintain stability and certainty at the highest levels of governance. The ARM’s model, however, represents a radical change: an Australian head of state with a unique mandate, one that is especially relevant to the most truly “national” areas of policy, such as foreign affairs and national security.

It is vital that the Australian Government has unity of intent and action in security and foreign relations. Ambiguity or, worse, outright discrepancy between prime minister and head of state tempts exploitation by adversaries and diminishes trust from allies and friends.

The problem starts in the electoral process. Any candidate for head of state would develop a platform to differentiate themselves. Any sensible candidate would campaign on matters of national importance – so defence and foreign affairs will be front and centre. If a sitting government is unpopular in one of these areas, a candidate for head of state may campaign based on frustrating their policies.

Moreover, having a national popular vote for head of state is likely to deter the kind of eminent apolitical figures Australians have enjoyed as Governor-General and instead attract partisan figures accustomed to a combative process. A popular mandate to do nothing at all is an oxymoron. An elected head of state will have an agenda and the will to implement it.

Once elected, the head of state’s term would stretch across at least two, but potentially three, electoral cycles (currently three years) for the Australian Parliament. In this time, the national mandate of the head of state would remain, but the party of government and their policies could change multiple times.

The ARM’s model effectively retains the current position entrenched by section 63 of the Constitution that the head of state must act upon the advice of ministers and cabinet. The issue, however, is that while this would be strictly true for matters of law or government action, it is unlikely to constrain how a head of state uses their platform.

The bully pulpit is a powerful tool for a popularly elected head of state: a lever that could be used to influence, and even change, policy through public sentiment. Moreover, how an elected head of state would represent Australia to the world is quite unclear. Would they faithfully enact the government’s foreign policy, or forge their own diplomatic agenda?

A head of state nearing the end of their term but seeking a legacy may feel particularly empowered to act at odds with the government.

It’s not hard to imagine a clash between head of state and prime minister. A progressive head of state elected on a platform of vigorously advancing human rights would likely conflcit with the kind of hard-line immigration policies the current Government holds. Similarly, a head of state intent on promoting Australian liberal values could undermine the pragmatic diplomacy needed with less like-minded countries. And, of course, on an issue as high stakes as China policy, divergent views are almost inevitable. A head of state nearing the end of their term but seeking a legacy may feel particularly empowered to act at odds with the government.

The most dangerous implication of the ARM’s model, however, is the head of state’s power as commander-in-chief. Currently, under section 68 of the Constitution, “[t]he command in chief of the naval and military forces of the Commonwealth is vested in the Governor-General as the Queen's representative.” While the ARM’s model does not state how section 68 might change, it’s fair to assume that a head of state would exercise this power based on ministerial advice. But the issue is more complex. Ambiguity persists around how section 68 can be exercised currently. Moreover, section 68 is supplemented by the Crown’s co-existing prerogative power of war. Precisely how these powers would operate in a republic must be made clear. A head of state acting independently with armed force or countermanding the cabinet’s instructions would be a fraught situation.

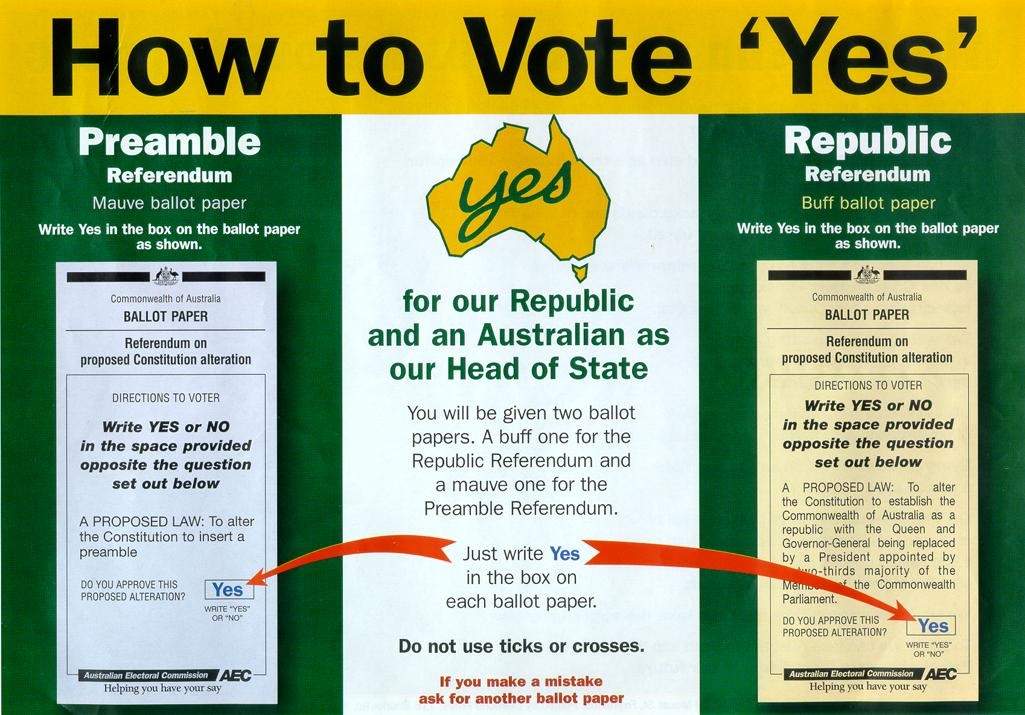

The irony of the ARM’s proposal is that it highlights the upsides of constitutional monarchy. Australia would be better served by going for a minimum-change model where, for instance, the head of state is nominated by the prime minister and elected by a two-thirds majority of a joint-sitting of parliament. In something as fundamental as constitutional governance, there’s no room for a sub-optimal model.