Historically, Australia’s colonial states in the 19th century were individually preoccupied with security before the act of federation shifted elements of responsibility to the Commonwealth government. For example, after early Australian pressure for Britain to colonise the island of New Guinea, the Queensland colonial government revived the issue of annexing East New Guinea in 1883. The motivation was fear of German control as well as a desire to recruit labourers from New Guinea to work on Queensland’s sugar plantations. Queensland’s push for the annexation of New Guinea is part of a long history of the state’s complex relationship with the Pacific.

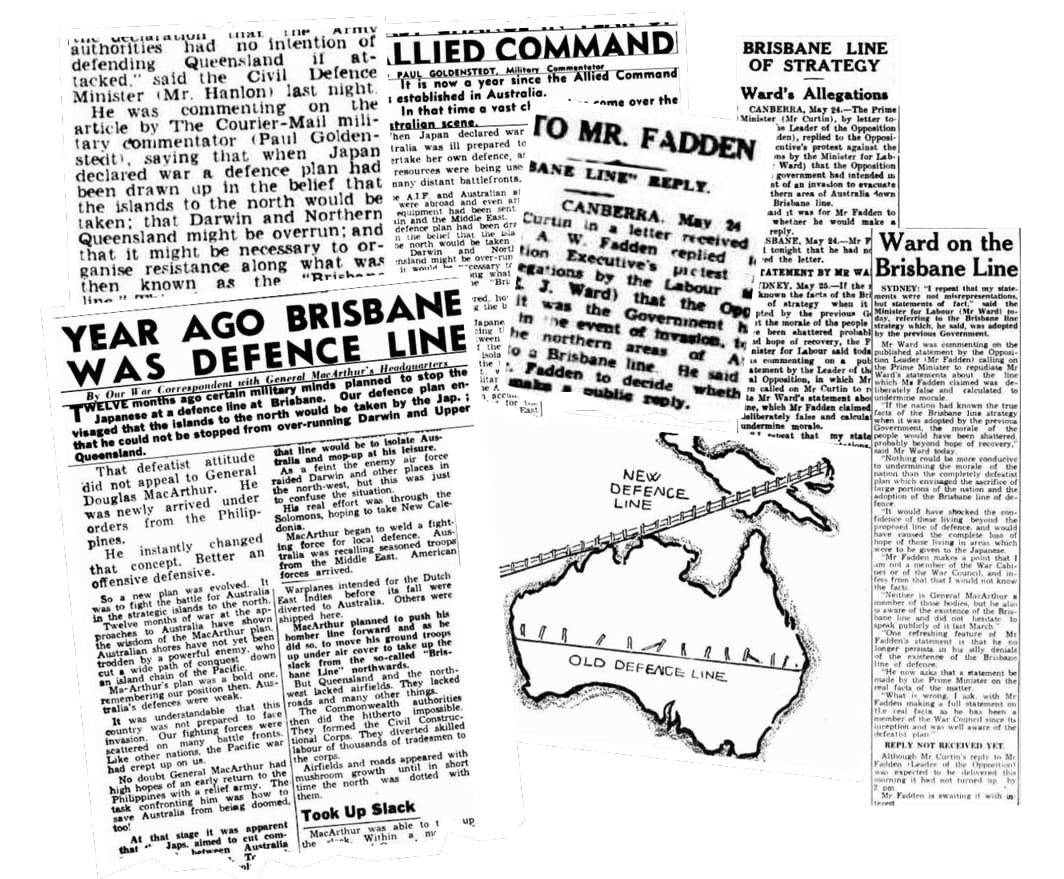

But even after Australia cemented its collective sovereignty in 1901, the division of power under a federal system still left tensions related to national security and international relations. This was illustrated by the so-called “Brisbane line” , a supposed plan to abandon northern Australia in the event of an invasion by Japan during the Second World War. The allegation generated significant controversy and was the subject of a Royal Commission of Inquiry in June 1943.

While the Royal Commission found that no such plan had been official policy under the Menzies government, the then War Cabinet had put in place strategies prioritising defence for vital industrial areas in time of war. Notably, the first contingent of US forces to arrive in Australia arrived at Hamilton Wharf in Brisbane on 22 December 1941. The first US camp (Camp Ascot) was established at Brisbane’s Eagle Farm racecourse.

In short, this underscored the geostrategic significance of Brisbane to regional warfare.

Fast forward to modern times and more “traditional” security threats often lean heavily on state policing. Non-traditional or emerging threats to national security, such as climate change and pandemics, expose both fault lines and strengths in cooperative federalism and the divisions of power and responsibility.

A 2021-22 report, for example, suggests Queenslanders contribute more than 27% of Australian Defence Force recruits, yet comprise about 20% of the overall national population. On food security, Queensland is a major agricultural producer for Australia, contributing more than 24% of Australia’s production annually. Queensland also accounts for a significant proportion of base metal production in Australia, which means the state’s response to transition to climate-safer jobs and industries is crucial in the challenges posed by the climate emergency.

Demographically, the Australian Bureau of Statistics revealed Queensland had the largest positive population change of any Australian state or territory for 2021, with a 1.4% population increase. Of course, this was in the context of Queensland having fewer internal lockdowns during the Covid pandemic compared with states such as Victoria and New South Wales. Nonetheless, Queensland demographics have changed, showing just how vital the state has become.

In terms of Queensland’s engagement with Pacific nations, the 51 Far North Queensland Regiment, an Indigenous army unit based in Queensland, has engaged in training Vanuatu units. Likewise, the role of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion in New Guinea is an important part of Australia’s shared history with Papua New Guinea. Brisbane hosts direct flights to Fiji, Indonesia, Nauru, New Caledonia, PNG, Samoa, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, where most other cities only offer two-part flights. Queensland is also home to Australia’s second-largest population of people claiming Pacific ancestry, just marginally behind New South Wales. If there is a link between settler communities in Australia and Australia’s soft power in the Pacific, this matters. Opportunities for sports diplomacy are significant, not least, for example, due to the quasi-religious status of Rugby League and the State of Origin series in Papua New Guinea.

All this should emphasise that states have consequences for national security. A number of state governments have ministers with portfolios that include matters related to the defence industry, as well as traditional responsibility for police, corrective services, fire and emergency. Areas such as resources, environment, housing, and rural communities can all have a national security dimension. But states generally don’t have an overarching national security portfolio.

For Queensland, a reorientation is needed – as well as a broader shift in national thinking. Federal national security bodies, including in operational, policy and educative agencies, should consider a greater presence in Queensland. Cooperative planning, including for potential civil mobilisation, will be essential in response to floods and fires expected to increase in intensity because of climate change, let alone for the prospect of an armed conflict as geostrategic tensions grow. More permanent structures are needed than the ad hoc or reactive processes of the present. This is consistent with broad observations made in the 2023 Defence Strategic Review.

Canberra serves its purpose well, but moves towards decentralisation of the public service are being considered and recognised as important. While the Australian Constitution does formally divide powers between states and the Commonwealth (and many are concurrent), there is still scope for a more cooperative version of federalism in matters of national security, including potentially through reliance on the implied nationhood power, for example. States, including Queensland, are central to national security risk management: outward in, rather than always inward out, may be the best hope to securing Australia’s future.