Senior figures of the Biden administration have given two critical speeches on US economic policy. First, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen last month set out the parameters of US-China economic relations, attempting to make clear that Washington was not driven by a compete-at-costs logic in its relations with Beijing. Some have described it as a laying the “terms of the economic peace” with which Washington was prepared to live. While couched in the language of competition, Yellen signalled a desire to cooperate where possible and to avoid a major decoupling of the world’s two most important economies.

Then last week National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan addressed the Brookings Institution on “Renewing American economic leadership”. While using a similar tone as Yellen, Sullivan sketched out a blueprint for American international engagement that, were it to come to pass, would represent a post-neoliberal orthodoxy for America’s approach to the global economy. For decades the United States has underpinned a liberal model for international economic relations, advocating unswervingly for the power of markets, price signals and the profit motive as the critical components of optimal economic organisation. Sullivan has laid out a vision in which state guidance of economy matters becomes pre-eminent.

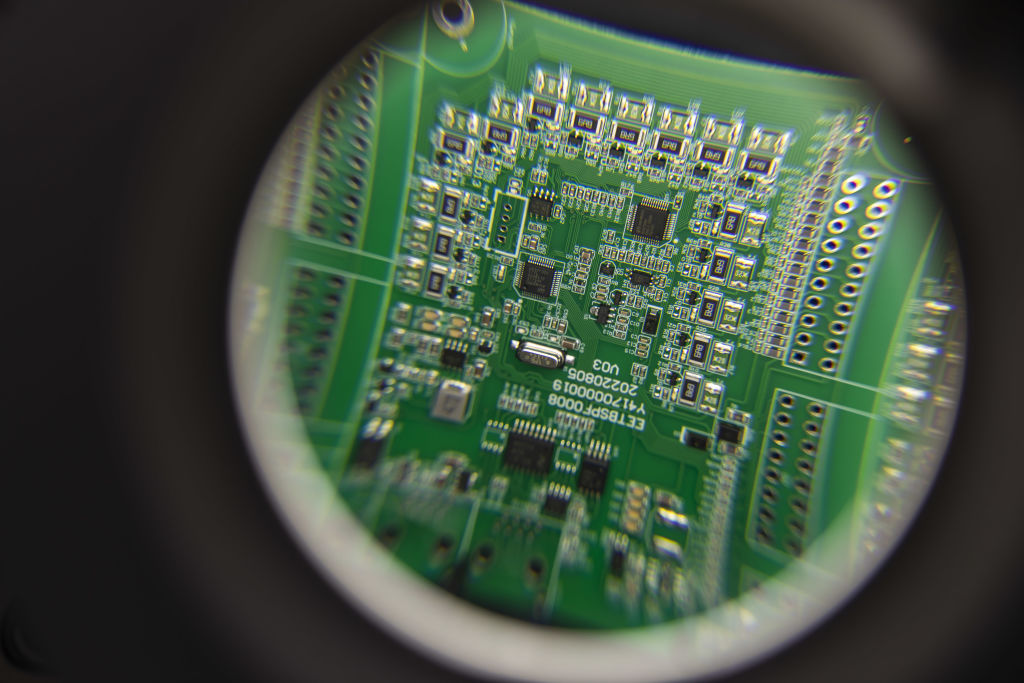

Sullivan argued that there were four reasons for administration’s change of direction. First, market forces untrammelled by the state had hollowed out America’s industrial base. Second, geopolitics had returned with a vengeance and neoliberal orthodoxy had weakened the United States in critical eras and provided key vulnerabilities in others, most obviously in semi-conductor production. Third, the climate crisis had been created by a classic market failure and finally, unfettered markets had created intolerable levels of economic inequality.

To address challenges that Sullivan frames in suitably epochal terms, state power must be brought to bear on how markets function. The speech was very high level, operating on matters of principle rather than practical details, but it made clear that the Biden administration was preparing a wide array of means to advance its ambition to rebuild America’s industrial base, better equipping its economy to grapple with great power competition with China, combat climate change and reduce inequality. These include public private partnerships, rewriting economic rules, as well as provision of economic incentives and subsidies to shift firm behaviour and investment choices and the creation of somewhat nebulous “economic partnerships”. These appear aimed to see off concerns from US allies and friends concerns about what looks suspiciously like the return of mercantilism.

While the four challenges Sullivan described are significant in-and-of-themselves, the fact that it was the National Security Adviser who sketched out the contours of this new economic landscape makes plain that preeminent motive force for this shift is security concerns about China. That said, given the fractured politics in America, the perceived threat from China is just about the only thing both sides of US politics can agree upon. It may be that a way to get traction on these issues is to define it as a means of tackling the China challenge.

Besides, critics of the liberal economic orthodoxy will take great heart from this shift in policy orientation from the world’s most important economic actor. Yet Sullivan’s reasonable tone and moderate claims belie the scale of the change that is in offing as the Biden administration seeks to rein in markets and use industrial policy to prosecute a multipronged gambit that could fundamentally reorder the global economy.

In some respects the Biden administration has already started down this path with the Inflation Reduction Act and Chips Act from 2022. They provide a welter of subsidies, tax breaks and loans to encourage investment in US semi-conductor production and green technology manufacturing base. The policies appear to be attracting investment. But they also illustrate the complexity of trying to reshape markets. For example, many electric vehicles assembled in the US by firms from “friendly” countries are ineligible for the tax breaks because of the many countries from which components are sourced rule them out of the current arrangements.

Some fear that the United States is trying to recapture markets and industry it lost to friends and partners, as well as putative enemies. To try to mitigate this concern the Biden administration has proposed a series of mechanisms to allow countries to coordinate on policy choices to “align incentives” so that market distortions can be minimised. These include the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and the US-EU Trade and Technology Council. But these are both nebulous proposals. Even if they work as intended – and IPEF in particular does not provide a great deal of reassurance on that front to date – they will create a bewildering array of distortions in markets, with consequences which are extremely difficult to discern, apart from the reality that they will increase cost and decrease efficiency.

Sullivan describes this internationalised industrial policy as intended to increase resilience, reduce risk and be more economically inclusive. But stripped of such high-minded rhetoric, it is not just about increasing American self-sufficiency in semiconductors and green technology, but about choking off China’s growth in key areas. Sullivan talks of protecting technology with “a small yard and high fences” yet it has maintained Trump-era policies to undermine leading Chinese telecommunications firms. Deliberate or not, this is reinforcing the sense in Beijing that Washington intends to contain China’s growth and limit is potential prosperity. This risks a further fuelling mutual suspicion and ill will.

The larger trend is clear: geopolitical concerns are now fundamental to the operation of markets. The end of the Cold War ushered in a period of liberal optimism in which competition between states was subordinated to the logic of the market. Biden’s move to reorient US economic policy shows us that we are now in an era in which markets will be subordinate to the logic of geopolitical competition. And that is one in which growth will be lower, costs higher, and risks of war are much greater than before. A grim future, indeed.