Outlining the Biden administration’s approach to China, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in March that the United States would be “competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be, and adversarial when it must be”.

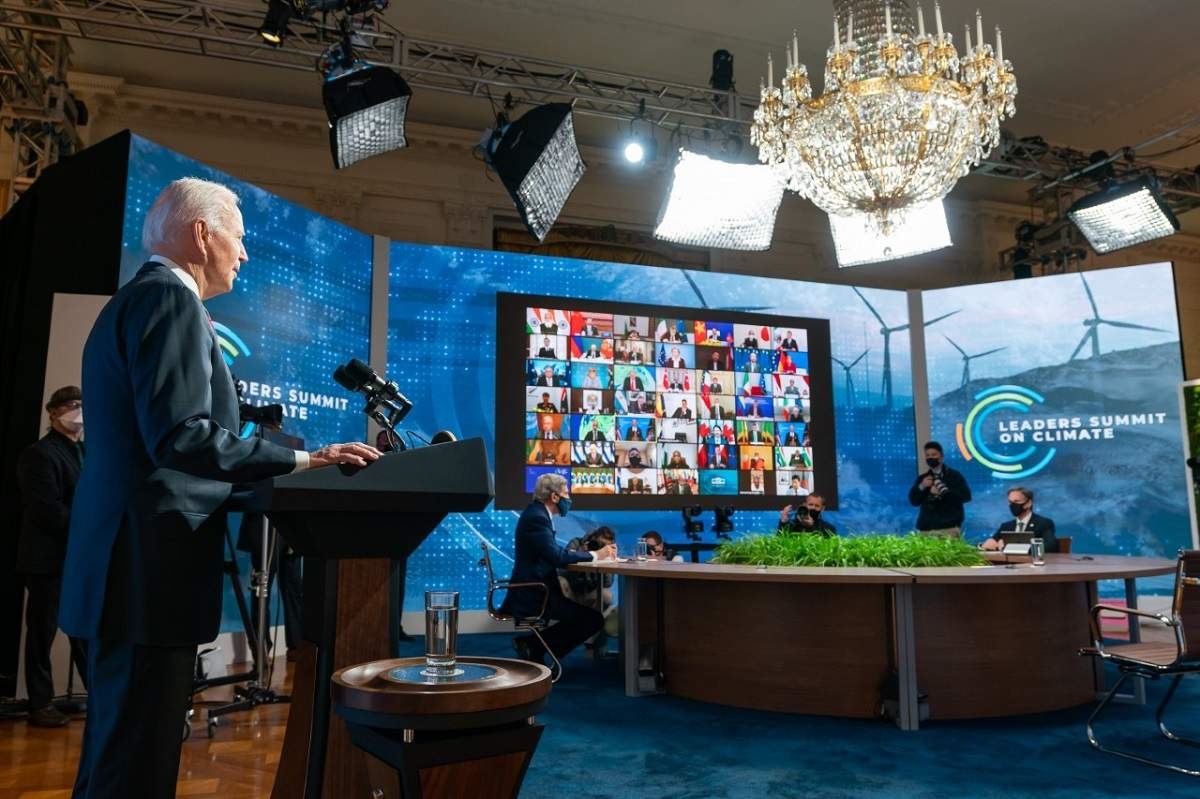

Climate change looked like an obvious vector for bilateral collaboration. In mid-April, “climate tsar” John Kerry became the first senior Biden administration official to visit China, releasing a joint statement on climate change with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua.

Since this time, China has made good on the most concrete part of the joint statement, formally accepting the Kigali Amendment to reduce the production of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). This is no small thing given that China is the largest producer and consumer of HFCs.

Proving causality is always difficult and it is quite likely that China would have ratified the Kigali Amendment irrespective of Kerry’s visit. However, as the US-China agreement on climate in the lead-up to Paris shows, even actions that would probably have been undertaken anyway at the national level without a diplomatic agreement can create a palpable sense of momentum.

Chinese policymakers have been reluctant to hand the United States easy political wins on climate without commensurate concessions elsewhere.

In this regard, it is notable that in the lead-up to COP26 – the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties – Sino-US cooperation on climate has not progressed much beyond the joint statement. Simply put, the political dynamics of the current relationship seem to preclude anything more than a tokenistic level of cooperation.

Climate change is key to the Biden administration’s attempts to rebuild US soft power and global leadership credentials. This gives developing countries leverage, especially those traditionally seen as obstinate or unambitious on climate. Appearing to toe the line on climate has been used as a diplomatic strategy to help procure vaccines, aid or other concessions from Washington.

In the same vein, Chinese policymakers have been reluctant to hand the United States easy political wins on climate without commensurate concessions elsewhere. Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian warned as early as January that cooperation on climate could not be decoupled from the broader bilateral relationship – unlike “flowers that can bloom in a greenhouse despite winter chill”.

China’s insistence on conditionality has directly undercut the Biden team’s preferred approach to neatly compartmentalise climate cooperation. Entering into any climate grand bargains with China would play poorly domestically and make many Asian capitals nervous.

Even in the rare instances where, at face value, China has appeared to offer unconditional cooperation, the United States has been unwilling to grasp it. Following the initial Alaska Summit in March, a Xinhua report of an agreement to form a working group on climate was subsequently denied by the US State Department.

Of course, it is possible that the Xinhua report was a gimmick. Another explanation is that the overriding logic of competition increasingly driving the bilateral relationship made even an ostensibly innocuous working group a bridge too far for the freshly inaugurated Biden administration.

These same exigencies of geopolitical competition apply to technology – one obvious area of potential Sino-US climate cooperation. China’s dominance in technologies such as photovoltaic (PV) modules will make decarbonising the US economy without Chinese imports impossible. Active cooperation, though, is a different story.

Self-reliance and maintaining the United States’ technological lead are part of the clear tenor of Biden’s supply chain review and Innovation and Competition Act. Both have a lot to say about sectors relevant to climate, which China wants to or already dominates, including batteries, rare earths, electric vehicles (EVs) and artificial intelligence (AI).

Rather than facilitating bilateral cooperation, climate change and related technology are quickly becoming part of more sophisticated US efforts to counter China. With an Indo-Pacific focus, the Japan-US Clean Energy Partnership pledges cooperation on “decarbonisation technologies” and supporting the regions’ energy transition. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (“the Quad”), which includes the United States, Japan, India and Australia, has a working group dedicated to cooperation on climate change (including technology), whilst the United States’ incipient “Build Back Better World” has climate as a specific area of focus.

As Beijing’s Made in China 2025 policy makes clear, China not only wants to be self-sufficient – it wants to dominate global supply chains and core technologies.

The good news is that China has plenty of intrinsic motivation to act to mitigate climate change. Just as pollution has been a grievance for Chinese citizens, the Chinese Communist Party recognises that catastrophic drought, desertification, flooding and sea-level rise (Shanghai is particularly exposed) will threaten its legitimacy.

Aside from mitigating China’s acute vulnerability to climate change, acting on climate has many other co-benefits. It helps replenish Beijing’s depleted soft power, spruiks its self-proclaimed Global South leadership credentials and curries favour with the European Union in particular.

Action on climate also gels nicely with Beijing’s self-sufficiency and innovation agenda. China is acutely aware of its dependence on energy imports, many of which come through the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca. Both chokepoints would likely be controlled by the United States in the event of a conflict. Rapid uptake of renewables helps mitigate this crucial strategic problem.

As the Made in China 2025 policy makes clear, China not only wants to be self-sufficient – it wants to dominate global supply chains and core technologies. As its demographic profile worsens, Beijing is increasingly emphasising innovation and moving up the value chain. Pursuing global leadership in technologies such as batteries, EVs, wind turbines and electrolysers ticks both boxes. Washington will not want to help enable these efforts.

It is possible that some level of geopolitical competition on climate will have a salutary effect. A darker scenario would see climate change-related technologies and supply chains politicised or weaponised in a way that actively hinders the transition.