The decision last month of a Special Chamber of the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea on a maritime boundary dispute between Mauritius and the Maldives reflects two dimensions to the engagement by international courts in resolving disputes among Indian Ocean states. First, it represents the latest judicial victory for Mauritius in its efforts to reclaim the Chagos Archipelago. More broadly, it reflects an emerging trend in the judicial resolution of international maritime boundary disputes in the Indian Ocean.

Mauritius brought proceedings against the Maldives in 2019 to delimit the maritime boundary between the Chagos Archipelago and the southernmost atoll of the Maldives. The case again brought the issue of sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago into the spotlight because the maritime claims of the Maldives and Mauritius can only overlap if the Chagos Archipelago belongs to Mauritius.

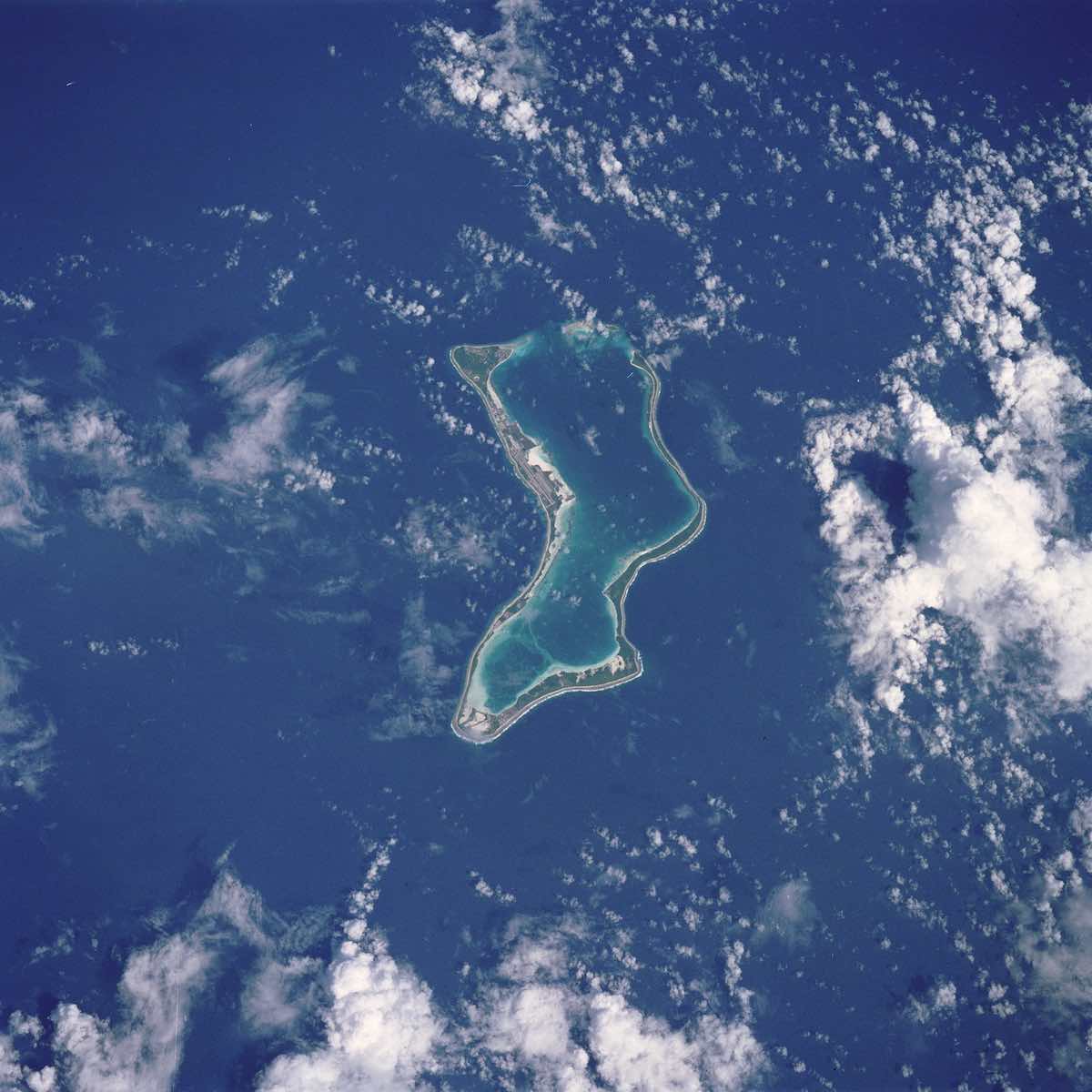

Britain detached the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius at the time of its independence with the promise that it would be returned to Mauritius when it no longer required it. Diego Garcia, the largest island within the Chagos Archipelago, was then leased to the United States for use as a military base.

In 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion in which it determined that the decolonisation of Mauritius was not lawfully completed with the separation of the Chagos Archipelago and that the United Kingdom was obliged to end its administration of the islands as rapidly as possible. But London still maintains that it has sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago despite the ICJ opinion.

Mauritius brought proceedings against the Maldives to determine their maritime boundaries under the compulsory dispute settlement process in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This allows parties to the treaty to turn to arbitration or adjudication to resolve disputes concerning its interpretation or application.

However, the Maldives argued that the Special Chamber had no power to hear the dispute because it didn’t have authority to resolve disputes over sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago. The Special Chamber confirmed that UNCLOS proceedings cannot resolve territorial sovereignty disputes. Questions must only concern the maritime matters addressed in UNCLOS, and UNCLOS does not deal with territorial sovereignty.

Mauritius instead argued that there wasn’t a territorial dispute before the Special Chamber, as the ICJ’s advisory opinion had already determined that the Chagos Archipelago was an integral part of Mauritius. For Mauritius, the issue has been resolved in its favour and it is proceeding accordingly in its interactions with its neighbours. Mauritius argued that although the ICJ opinion is not legally binding, its determinations were “not devoid of legal effects”.

The Special Chamber agreed that “the decolonisation and sovereignty of Mauritius, including the Chagos Archipelago, are inseparably related”. Whereas the ICJ had previously carefully sought to deny that it was deciding any territorial sovereignty dispute between the United Kingdom and Mauritius, the Special Chamber more readily acknowledged the “unmistakeable” and “considerable implications” for the United Kingdom’s sovereignty arising from that opinion. As the Special Chamber accepted that Mauritius, and not the United Kingdom, was entitled to assert rights over Chagos Archipelago, the Maldives objections on this question were rejected.

It is notable that Indian Ocean coastal states are often willing to compel the use of adjudication or arbitration when those discussions do not produce results.

In taking this approach, the Special Chamber has effectively transformed a non-binding opinion into a legally binding decision, albeit only binding between Mauritius and the Maldives and not on the United Kingdom. The litigation strategy pursued by Mauritius has borne fruit in ensuring an advisory opinion that was not supposed to resolve a bilateral territorial sovereignty has truly had that legal effect.

The case will now proceed to the determination of the maritime boundary between the Maldives and Mauritius, although a decision may not eventuate for another two years.

Mauritius-Maldives is not the only maritime boundary dispute in the Indian Ocean pending before an international court. Somalia instituted a case against Kenya in 2014 based on each state’s acceptance in advance of the Court’s jurisdiction rather than under UNCLOS. The public hearings on the boundary delimitation will be held next month.

This current engagement of international courts with maritime boundary delimitations in the Indian Ocean is not new. Bangladesh instituted proceedings under UNCLOS in 2010 to resolve its maritime boundary disputes with India and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal and led to two awards delimiting respective maritime zones.

While maritime boundaries are most commonly bilaterally negotiated by states, it is notable that Indian Ocean coastal states are often willing to compel the use of adjudication or arbitration when those discussions do not produce results. Resort to an international court will only be possible if states are parties to UNCLOS or, alternatively, consent to the ICJ’s jurisdiction. All but four Indian Ocean states are parties to UNCLOS so there remains considerable potential for the judicial resolution of the many outstanding maritime boundary disputes in the region.

However, even if a state is party to UNCLOS, there is an option to exclude the resolution of maritime boundary disputes from compulsory arbitration or adjudication. Australia has taken this path. When a state does so, compulsory conciliation may instead be undertaken, as happened when Timor-Leste pursued conciliation against Australia in 2016 and resulted in the Maritime Boundary Treaty.

While states are not always keen to refer their disputes to third parties for a legally binding decision, experience has shown not only how peaceful resolution of differences in the region can be achieved, but also the potential utility of international litigation to further other political agendas – in this case, the further affirmation of Mauritius’ sovereignty over the Chagos.

This article is part of a two-year project being undertaken by the ANU National Security College on the Indian Ocean, with the support of the Australian Department of Defence.