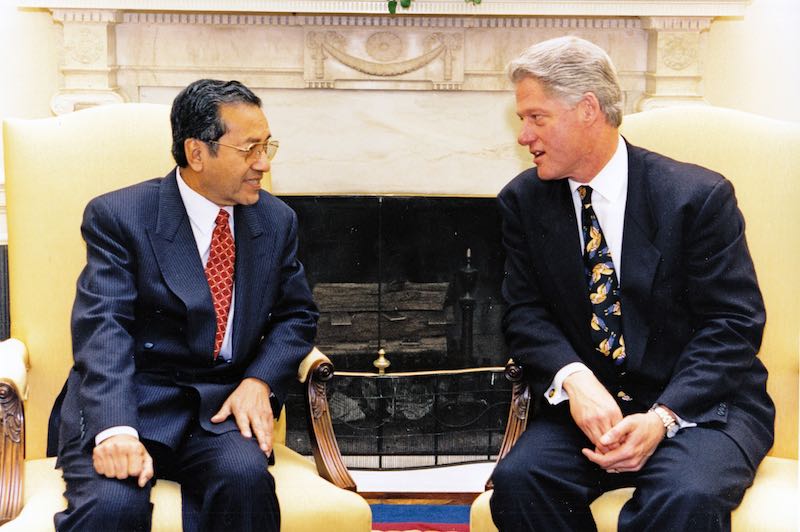

Since returning to power after his stunning election victory in May 2018, the 93–year–old Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad has made a series of comments reflective of weaker states’ views of the evolving Asian order in the Trump–Xi era. These include a firmer stance on the South China Sea disputes, Malaysia’s relations with the Asian powers (especially concerning the controversial China–backed infrastructure projects and Japan’s regional role), as well as the future of multilateral trading arrangements.

In the current age of connectivity–building, Malaysia enjoys some bargaining chips thanks to its geography, between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Mahathir’s comments that “warships attract other warships” in particular – alongside his peace proposal for ASEAN countries to patrol the disputed waters by small boats “to deal with pirates, not to fight another war” – have generated discussions in foreign policy circles about whether a “Mahathir Doctrine” is emerging in Malaysia’s external policy.

This extends to how the views of the world’s most senior statesman might translate into regional visions amidst the escalating US–China trade confrontation and global uncertainty.

Judging from Mahathir’s recent remarks, as well as his policies during his first premiership from 1981–2003 (“Mahathir 1.0”), three elements can be identified as the core constituents of the emerging “Mahathir Doctrine”:

- The South China Sea should be a sea of cooperation, connectivity, and community–building, not confrontation or conflict.

- Diplomatic consultations, not military swaggering, are the key to managing and resolving any inter–state disputes in East Asia and elsewhere.

- While all countries, big and small, are welcome to play a constructive role in the widening East Asia community building via integration and creation of bigger markets, weaker states’ interests must be respected, protected, and fulfilled.

Each element entails smaller states’ sensitivities about the dangers of deepening big power rivalries. Each embodies the Mahathirist oxymorous approach to international affairs (i.e. managing realist realities via idealist ideas of integration and institutionalisation). Each aims at building on the enduring legacies of the leader’s first tenure, when Malaysia acted as an “activist Lilliputian” in the post–Cold War East Asia.

Under Mahathir 1.0, Malaysia punched above its weight by proposing region–wide initiatives, for example, the idea of East Asian Economic Grouping (EAEG) in 1989. Malaysia pushed transformational envelops, engaging and accommodating former foes such as China in the ASEAN–based dialogues since the early 1990s, and pushing through the ASEAN Plus Three (APT) cooperation at the height of the Asian financial crisis. Malaysia also initiated and institutionalised a special working group for the idea of a Singapore–Kunming Rail Link (SKRL), to promote and coordinate the construction of electrified double–tracking and missing links for a rail network connecting seven ASEAN countries and southern China, among numerous other proposals.

Not all of the Mahathir 1.0 initiatives were successful (e.g. the EAEG idea never took off, even after it was watered down as the East Asian Economic Caucus, or EAEC, in 1993). He was criticised by many for his various anti–Western and anti–Semitic remarks, and several of his projects either failed to yield results proportionate to the resources committed (the Langkawi International Dialogue) or simply lost steam after he left the scene (engagement with Africa).

Nevertheless, these shortfalls and weaknesses – alongside his authoritarian governing style at home – did not stop many from the Muslim and developing worlds from viewing him as a bold Third World leader.

Fast–forward to August 2018, Mahathir 2.0 faces rather different external and internal contexts.

Externally, the US is still the world’s strongest power, but with increasingly uncertain commitment and eroded credibility under the unpredictable Donald Trump. China is becoming more powerful and more assertive, promoting Belt–and–Road economic inducement while creating new realities at sea under Xi Jinping. The growing uncertainties surrounding US–China relations are pushing regional players such as Japan, India, and Australia to amplify their activisms under various versions of the “Indo–Pacific” strategy, creating both opportunities and challenges to weaker states such as Malaysia.

Domestically, while the unprecedented change of government after the May 2018 elections has unleashed fresh energies, hopes, and democratic space for the multi–ethnic country, the new Malaysia confronts an array of new and old challenges. This ranges from government debt and fiscal deficit, to intra–coalition bargaining within the ruling Pakatan Harapan, and from partisan and special interests to identity politics.

The Mahathir Doctrine – driven and constrained by these conditions – is expected to manifest most profoundly in three policy areas.

First, in preserving small–state interests in the South China Sea. Echoing Mahathir’s stance, already Defense Minister Mohamad Sabu has emphasised that both US and Chinese warships should not linger in Malaysian waters, while Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah advocated ASEAN to play a leading and active role in managing the situation in the South China Sea.

Second, Malaysia will look to cushion the escalating big power competition in both strategic and economic spheres. This is demonstrated by vowing to remain neutral, engaging all players and stressing consultations, consolidating ASEAN centrality, and widening the layers of Asian multilateralism. Foreign–funded projects will also be welcomed when fair, sustainable, and truly mutually beneficial.

Third, the emphasis will be on exploring more favourable trading arrangements that allow small and developing nations to compete with the more developed ones in the unequal international system.

Regardless of whether the doctrine will be expressed explicitly, Malaysian external policy under Mahathir 2.0 is aimed at ensuring a stable, peaceful, and productive external environment conducive for domestic growth and regional resilience. To pursue these goals, Putrajaya is building its bargaining strength by forging multilayered coalitions across sectors, adopting issue–linkage approach, and leveraging on the legacies of Mahathir 1.0.

In the current age of connectivity–building, Malaysia enjoys some bargaining chips from its geography, as the southernmost land of the continental Eurasia, between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Malaysia benefits from strategic neutrality, diplomatic assets (in bilateral links as well as ASEAN–based multilateralism), and an expressed readiness to explore platforms of partnerships with like–minded nations, such as an enlarged EAEC to take in Central Asia and India, as well as a more sustainable, self–strengthening and inclusive model of connectivity cooperation with China and other players.

Talk a high–speed rail right through the Peninsular Malaysia is a further example. This would join a Eurasian rail network, to serve as a model of infrastructure partnerships where foreign investments facilitate technology transfer, add jobs, and broaden market access.

The Mahathir Doctrine, in essence, is about recalibrated equidistance. It is equidistance in that Malaysia insists on not siding with any power. It is recalibrated in that while the small state continues to anchor in Southeast Asia, it is now more determined to seek more balanced alignment by leveraging on its commercial, civilizational, and connectivity links with East Asia – and beyond – to address growing domestic needs and external uncertainties.