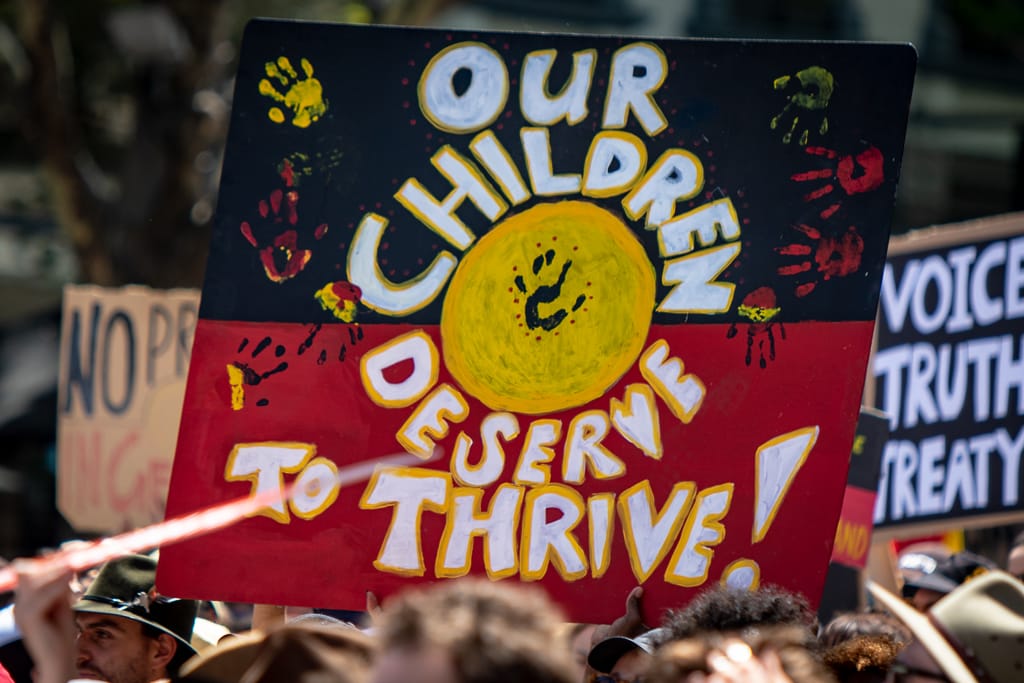

The upcoming referendum for an amendment to the Australian constitution, if passed, will see Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders recognised in the nation’s founding document for the first time. It will also lead to the creation of a body to advise the federal parliament and government on policies relating to Indigenous Australians, a constitutionally enshrined right to have a “Voice”, as the body will be called, on matters that affect them.

As an observer from abroad, it seems extraordinary that a country such as Australia, one that largely aligns itself with “Western” norms and values of freedom and democracy and a liberal outlook on life, has yet to recognise the people that originally inhabited the continent for close to 60,000 years. As a former colony, like my own country India, Australia has many contradictions, not unlike other one-time imperial dominions, and the treatment meted out to the indigenous people of the country has been marked by injustice.

Beyond the harms done to them, this history hampers the presentation of Australia globally, with concerns often raised in international forums. Regular public acknowledgement of the original owners of the land and this year establishing an Office of First Nations Engagement within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade are helpful steps in shifting attitudes. However, enshrining rights of peoples in the constitution will be more important in respect of how many partner countries will view Australia.

India will be one such friend watching. New Delhi will not get entangled in “domestic issues” of a Yes or No campaign, but will assess the outcome. India has been pressured over its own internal issues. To many, it may seem that values and principles differ between the countries, but not formally recognising the indigenous community in the constitution, unlike in India where the tribal groups are, shifts the equation.

For a referendum to pass in Australia, it requires a double majority, with more than 50 per cent support nationwide and a majority in four of the six states – and achieving this will not be easy; polls are currently divided. There are muddled views about what kind of change can be expected, how the new body will integrate with the government, and the extent of its influence, with many indigenous peoples themselves wavering in support. While the domestic aspects of the debate will largely be lost on global partners, the outcome of the vote, especially a “No” vote, will have ramifications.

A “No” vote from Australia would call into question the authenticity of its words and actions abroad at a time when authoritarian regimes present themselves as the vanguard of a shift away from “liberal internationalism”. It would not be the first instance of a Western nation turning its back on values presented to be universal. Sweden rescinded its Feminist Foreign Policy following 2022 elections, while the United States overturned national abortion rights and more recently eroded anti-discrimination laws. These carry reputational effects, diminishing influence.

The effects are not always obvious – countries will still turn to Washington especially as a necessary partner – but can result in greater pushback from countries such as India when questions of internal domestic issues arise. The more Western countries are seen not to follow through on the values they preach, the more pushback they will receive. And this goes beyond governments. Organisations that advocate for inclusive policies would be unable to point to Australia as an example; and genuine efforts to safeguard the rights of minority communities will face more resistance.

India’s partnership with Australia has exploded in recent years, across issues of trade and security, cooperation on climate governance, and cultural and educational ties. A focus on community is at the core of many of these new deals, as well as “quiet diplomacy” about rights concerns in India. A perception that Australia has not lived up to its values will be belaboured by many in India, possibly to the detriment of the growing relationship between people, institutions and communities.

A “Yes” vote, conversely, will be feted and hailed as an important step to counter internal fissures, even if the result itself will ultimately be a short news cycle in India. But while that can be expected in today’s news world of fast communication and social opinion, there is also the more enduring question of trust.

With Indians one of the fastest growing migrant groups in Australia, trust is determined by more intangible senses, with people asking themselves whether Australia will take care of its communities, including migrants, or are scattered instances of racism and discrimination likely to grow. These answers, of course, have no direct connection to the referendum vote but are in the social milieu that determines attitudes. A display of majority support for Indigenous Australians can only help. A potential trust deficit with the Pacific Island countries on a negative vote could undermine any joint efforts on climate between Australia and India in this region or the larger Indo-Pacific.

Australia and India’s growing regional collaboration has been based on a variety of shared interests, including a commitment to climate resilience efforts, diversifying from China, and addressing a deficit on global leadership. None of this is likely to change drastically regardless of the vote. Even with a “Yes” vote, Australian policymakers might be reticent about speaking seriously on India’s internal politics. A “No” vote and continuation with the status quo will be regarded as a missed opportunity, even from a friend like India.