Last week, US President Donald Trump announced via Twitter that he had authorised his staff to begin “initial protocols” for the transition process. In the same breath, he vowed to continue what is a fruitless campaign against alleged voter fraud. In subsequent tweets throughout the week, Trump went to great pains to communicate to his supporters that this authorisation did not represent a concession. Sadly, unsurprisingly – whatever you want to call it – this may in fact be the closest thing we ever see to a Trump concession.

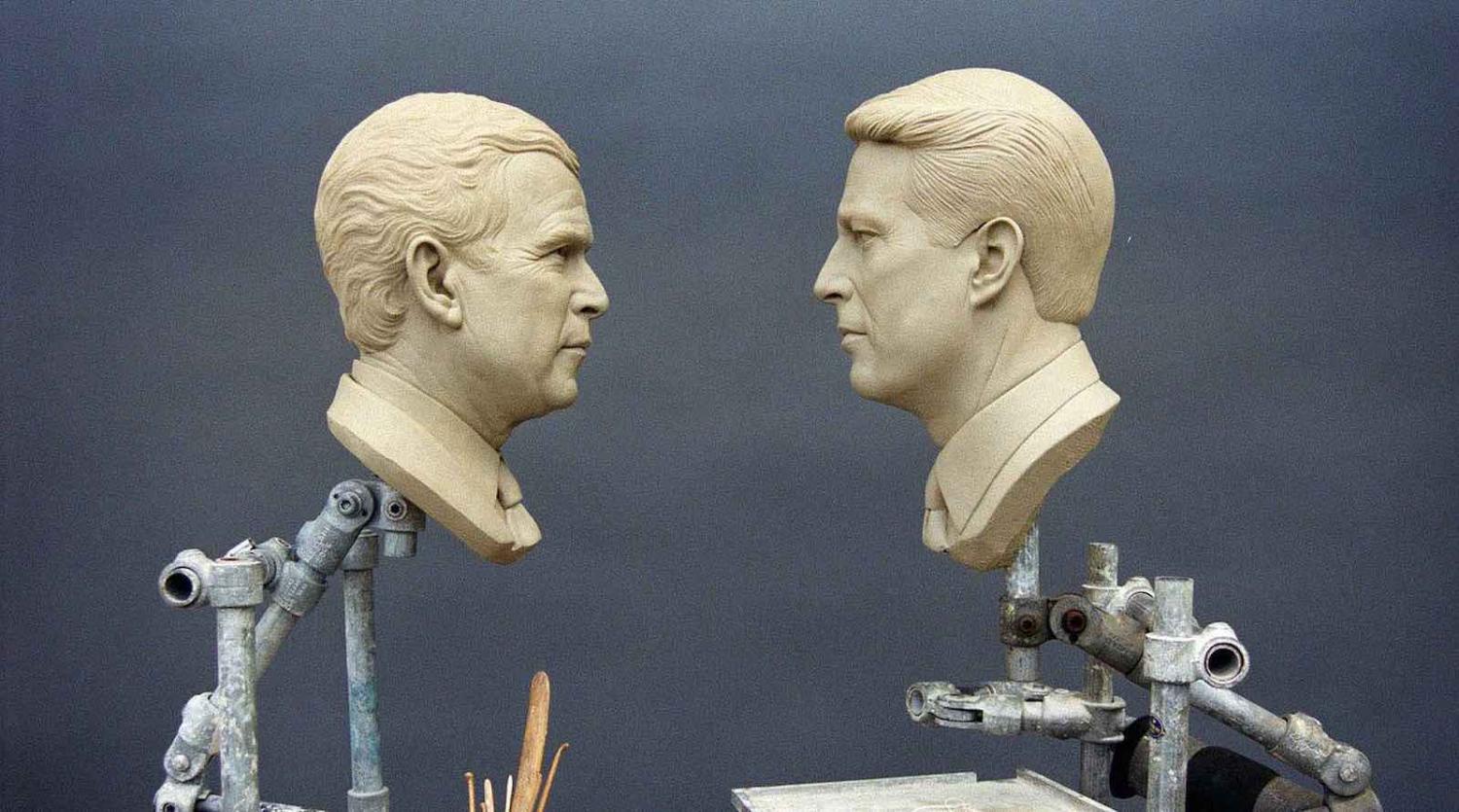

Society will often look to the past and draw from examples that might help us better understand the current situation. In this case, many are focusing on the contested election in 2000 between George W. Bush and Al Gore. Commentators point to that election, and the fact that it wasn’t officially called until mid-December, as a sign that there may yet be a smooth transition of power between Trump and president-elect Joe Biden.

The 2000 presidential election ended on 12 December, when the US Supreme Court intervened in what was the most closely contested US presidential election ever – as close to a dead heat as one could get – and essentially called the election by blocking a recount of votes in Florida. As a result, victory went to Bush, who had lost the popular vote but, by virtue of his exceedingly narrow and hotly disputed victory before recount in Florida, managed to eke out an Electoral College majority.

America needs to come to terms with the fact that even after Biden is sworn in, there will be millions of Americans who have no faith in the institutions that uphold the democratic system.

While volumes have been written about the Bush v. Gore decision, the results of that election, and the events that followed, were also strongly influenced by something else entirely – the fact that, despite his strong disagreement, Gore acceded to the decision made by the Supreme Court.

Concession is a custom – not something required under law – so it is worth remembering that Trump does not have to concede in order for Biden to be sworn in as the 46th president of the United States. But of course, it would be a whole lot smoother if he did, and it would go a long way to restoring America’s reputation on the world stage.

By conceding, Gore paved the way to a more peaceful transition of power. Transition is based on a degree of goodwill, and in 2000, Gore made the ultimate sacrifice. After a long and determined legal fight, he declined to challenge the authority of one of America’s most revered institutions. Instead, he chose to preserve the legitimacy of the democratic system.

Trump is no such man. Domestically, he has spent the last four years sowing mistrust, peddling disinformation and elevating conspiratorial beliefs. Abroad, this has translated to a “go-it-alone” approach to foreign policy – including withdrawing from multilateral agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Paris Agreement on climate change, picking fights with long-term allies such as Australia and South Korea, and sidling up to authoritarian leaders such as Vladimir Putin.

Of course, Trump was unlikely ever to concede officially – after all, think what kind of message that would send to his base. Millions of Americans voted for Trump and – although he would never say it out loud – his post-presidency retirement plans depend strongly on maintaining their support. It is likely that Trump will ride the “rigged election” train all the way to 20 January, and perhaps beyond.

This sentiment is not entirely new. Gore may have conceded, thereby preserving the legitimacy of the US Supreme Court; however, a key legacy of Bush v. Gore was the undermining of the public’s faith in the fairness of American elections. A straight line runs from the Bush v. Gore decision to the “armies of lawyers” that have been dispatched to monitor elections since then. In 2020, thousands of lawyers, volunteers and poll watchers came together to monitor the election in what both Republicans and Democrats say is their largest election-year legal campaign in history.

America needs to come to terms with the fact that even after Biden is sworn in, there will be millions of Americans who have no faith in the institutions that uphold the democratic system.

As one of America’s oldest allies, Australia needs to be ready to defend this system against those who would seek to destabilise it. Since Biden’s election victory, there has been increased talk about a revival of the “liberal international order”.

In Australia, we often refer to this as the “rules-based order”, and if my time spent researching this topic has taught me anything – apart from revealing a general lack of consensus over what the term actually means – it is that countries don’t like being told to follow the rules by other countries that don’t follow the rules themselves.