In July 2020, a plane carrying an estimated 500 kilograms of cocaine allegedly destined for Australia crashed on the outskirts of Papua New Guinea’s capital Port Moresby. Because PNG’s Drug Act of 1952, a remnant of country’s colonial history, does not cover substances such as cocaine and methamphetamines, the Australian pilot manning the aircraft that was only charged with illegal entry (entering the country without a passport) and later extradited to Australia along with another man. Had the pilot been prosecuted under PNG’s Drug Act, he would have had a sentence not exceeding two years in prison. But in Australia, he faces much stiffer penalties.

Last month, police discovered a methamphetamine laboratory at the Sanctuary Hotel in Port Moresby, managed by an Australian. The man was not charged with drug offences because the Drug Act doesn’t account for meth. He was, however, charged with the illegal possession of weapons. Police described the outdated drug laws as a “slap in the face” given the resources and time put into investigating, “yet we cannot take it to the court process”.

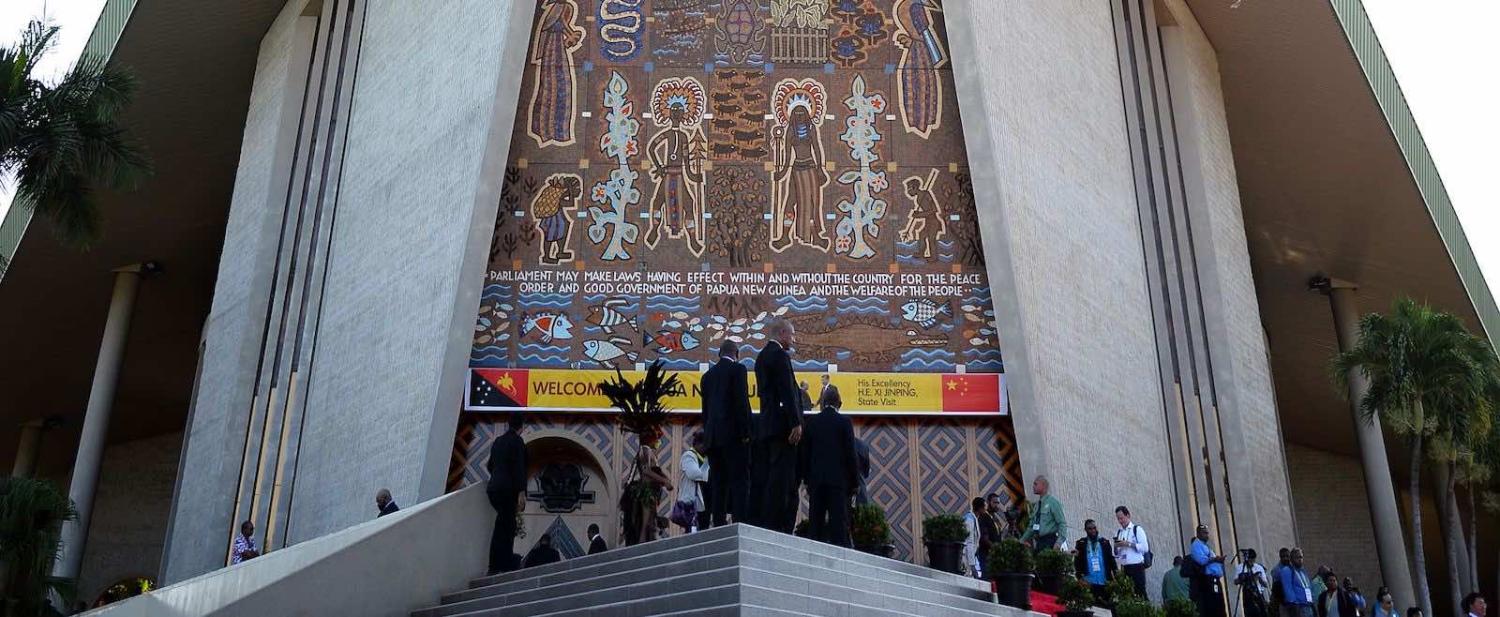

Laws in PNG are made by the legislators – Members of Parliament. These two cases highlight the lack of attention MPs have paid towards their law making responsibility.

How did PNG get to this stage?

PNG ranks among the highest clientelistic societies of the world, where voters are more inclined to vote for MPs based on direct material or monetary benefits, rather than their role as lawmakers. But this expectation from voters, to some extent, was created by the reforms engineered by politicians in 1995 and 2014, which made MPs directly responsible for the delivery of goods and services.

MPs focus on meeting local, direct and personal benefits of the voters that improves their chances for re-election, while the voters neglect the failure of their MPs to make better laws.

The 1995 reform dissolved the provincial governments, and replaced them with the national MPs. The MPs elected to make national laws now sit in the provincial assembly and manage provincial affairs. Previously premiers, who were elected to the provincial assembly, played this role. The provincial assembly now comprises the governor of the province, and the open MPs who represent the districts in the province.

The second reform in 2014 created the District Development Authorities (DDA). The DDAs are now chaired by the open MPs, and staffed mostly by political appointees.

These two reforms gave the MPs the dual responsibilities of making laws as well as managing provincial and district affairs. The component of funding that these MPs have the most control over is the Constituency Development Funds, called Services Improvement Program funds, or SIPs. The governor controls the Provincial SIPs (or PSIP), and the open MP controls the District SIPs or DSIPs.

As chairs, the politicians dictate priorities and allocation of the funds, which at its height reached a total of K50 million per year (A$20 million). A survey of the use of these funds in 2014 showed that services were regressing, and even though acquittals for these funds are very poor, the funds remain popular with the MPs.

Ironically, despite the poor service delivery, constituentices see the role of MPs as service deliverers and project managers, and not as lawmakers.

The direct access that MPs have to millions of kina, and the discretion they enjoy over the application of this money, creates an expectation among voters that they can transact their votes for direct personal benefits. The non-existence of acquittals means the MPs can prioritise for funding just about anything from school fees to “haus krai” contribution (money for funeral expenses). In a vicious circle of a principal-agent relationship, the MPs focus on meeting local, direct and personal benefits of the voters that improves their chances for re-election, while the voters neglect the failure of their MPs to make better laws.

By focusing on provincial and district affairs, MPs are neglecting their mandated role as lawmakers. The government rushes through legislation and controversial amendments to the country’s constitution – such as the extension of the grace period under Peter O’Neil, which was intended to prevent a vote of no confidence, or the reduced parliament sitting days – without much debate. MPs are happy to vote on it, get their SIPs, and go to their provinces.

The only entity that stands between the executive dominated parliament and reckless amendments to the constitution is the PNG Supreme Court, which has ruled several amendments unconstitutional.

At the other end of the spectrum, proposed laws that are badly needed remain unattended. For instance, the proposed Decentralisation Act prepared by the Constitutional Law Reform Commission, which, among other things, attempts to prevent politicisation of the SIP funds is yet to be debated and passed into law. The proposed amendments to the Organic Law on the Integrity of Political Parties and Candidates, which includes efforts to increase female representation and restore some form of stability in parliament, is another that has not been debated. These two pieces of legislation were proposed after extensive consultation and research conducted by the mandated entities.

Reacting to bad press and the humiliation of criminals walking free, the government recently passed the Controlled Substance Bill 2021 to bridge the gap in drug laws that makes prosecution of cocaine and methamphetamine impractical. The new law increases the penalties for production, consumption, and trafficking of dangerous drugs, including methamphetamines and cocaine. The highest penalty is life imprisonment without parole.

PNG needs a proactive approach to reviewing its laws in the face of the changing global landscape. MPs should restrict their roles to lawmaking. Funds that MPs control can be given to existing government departments. The MPs should provide oversight and scrutiny instead.