Last Wednesday, two days after the Philippines mid-term elections, the loose coalition of forces that amounts to an opposition were having a crisis meeting.

They were moving quickly for fear of what convenor Corazon “Dinky” Soliman described as a “horror scenario” – that the vice president Leni Robredo would be impeached and replaced by Duterte’s former personal assistant and now Senator, Christopher “Bong” Go.

“They could easily do it,” said Soliman in an interview cut short by the meeting. “Duterte now controls both the House and the Senate.”

So what did the opposition forces intend to do about the possibility, and to take the fight up to President Rodrigo Duterte?

That was a lot less clear. There was vague talk of demonstrations and continued activism, of reaching out to the urban and rural poor. The truth is that the opposition in the Philippines, having failed to make any impact on Duterte’s continued popularity, is in disarray and having trouble with coherence, let alone planning for the future.

Last week’s mid-terms were a disaster for them. Not a single member of the so-called “Otso Diretso” (straight eight) of Senate opposition candidates was elected. The best-known face on the ticket, and the one scoring most votes, was the Liberal Party’s Senator Bam Aquino, scion of a political dynasty that includes two former presidents. He finished 14th in the count and failed to be re-elected.

In what was seen as a referendum on Duterte’s strongman rule, candidates backed by the President won nine out of the 12 available Senate positions, removing the main check on his power.

The Philippines has a weak party system, with voters identifying more with individuals and family dynasties than with parties. Political parties rise and fall quickly, have little grass-roots presence and tend to be flags of convenience, with candidates sometimes running under more than one banner, and switching sides to the victors after an election.

Therefore, it is hard to talk about the opposition as a connected force. In the leadup to Monday’s poll, a coalition of Liberal and other opposition parties put together the so called Osto Diretso ticket. Why only eight candidates for a possible 12 positions?

According to the Leader of the Akbayan Party, Senator Risa Hontiveros, it was because the various parties involved could not reach consensus on more than eight. “I was certainly arguing that we needed a full ticket.” Others involved vetoed candidates who were seen as too left wing, she says.

In a country where an estimated 30–40% of voters lack the money for food security, the Opposition comes across as urban based and middle class.

Both Hontiveros and Soliman admit they lack presence on the ground outside Manila.

Meanwhile, “yellow” – the colour of the Liberal Party, and once associated with the wave of optimism surrounding the people power revolution that deposed dictator Ferdinand Marcos – has become a dirty word. Says Soliman, “The president has succeeded in demonizing the values of democracy … by saying that that's all yellow, those are just yellow values.”

Soliman served as secretary of the Department of Social Welfare and Development under the administrations of presidents Benigno Aquino and Gloria Arroyo. She is now the convener of Tindig Pilipinas, a coalition of political parties and NGOs opposed to Duterte, formed after his election in 2016.

The truth is that the opposition in the Philippines, having failed to make any impact on Duterte’s continued popularity, is in disarray.

In the early days, she says, the Liberal Party were reluctant to be involved, preferring to work with the new president. Other political parties, such as the Gabriela Women’s Party, have in her view failed to call out Duterte on his misogynist comments because key representatives were given government positions.

Soliman says the opposition will struggle to cut through until it finds a leader who can take on Duterte’s hold on the popular imagination. While vice president Robredo accepted the title of leader of the opposition for the purpose of the election campaign, it is not clear she will continue and she “hasn’t got the persona”.

There had been hopes that former Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, who was impeached under Duterte in 2017, might join the opposition ticket for the Senate. A year ago, she was a star turn at Tindig Pilipinas rallies, but today she has retreated from public life.

Journalist Maria Ressa, founder and editor in chief of the independent web-site and social media news site Rappler, is facing her own troubles – a raft of criminal libel and tax evasion charges that could see her jailed. In her view, the opposition in the Philippines has failed “the same way the Democratic Party failed in the USA” – through pursuing a brand of elite politics that has left it out of touch with ordinary people and powerless against misinformation spread through social media. Opposition figures in the Philippines are “behaving like politicians rather than like leaders”, jockeying for individual advantage rather than uniting against a common enemy.

Meanwhile, the impeachment threat against Robredo is real – and has already been threatened over a video message she sent to the United Nations criticising the war on drugs.

So where to from here for the opposition forces?

One of Duterte’s most formidable opponents and critics is Senator Leila de Lima. Formerly head of the human rights commission and then justice secretary under the Aquino administration, De Lima investigated killings by the so-called Davao death squads during Duterte’s time as mayor of that city.

She became a senator in the same election that brought Duterte to power, but was jailed shortly afterwards, in February 2017, on drug charges that have been described by Amnesty International as entirely fictitious, and which have yet to be tried.

Her jailing has largely neutralised her as a political force. While she is allowed visits from her staff and lawyers, journalists and others must apply for a court order to see her – which so far has never been granted.

She lives in a cell just large enough for a bed and a small table, on which she continues her work as Senator as best she can without access to computer or the internet. Documents are brought to her by her staff. De Lima answered written questions I sent to her.

She says she prefers to understand the election result as a measure of “information asymmetry” in Filipino society, rather than the commonly accepted view that it confirms a preference for autocratic rule rather than liberal democracy.

Numbers of extra judicial killings are being obscured. With the Duterte administration’s proven acuity in propaganda and misinformation, coupled with the growing fear among members of the press to report on matters of public interest … the Filipinos may not yet be seeing the true and complete picture of the state of the nation.

De Lima believes that nothing short of a major economic crisis or corruption scandal can now impact on Duterte’s popularity. Foreign protests, both over her jailing and the continuing “war on drugs” are seen as foreign meddling, she says.

Nevertheless, the Opposition should continue to focus on human rights and democratic principles, she says.

With a renewed mandate after the mid-term elections, the killings could actually get worse … Mostly, we are hoping that the International Criminal Court acts soon enough and start an investigation on the extra-judicial killings committed by the Duterte administration in its war on drugs.

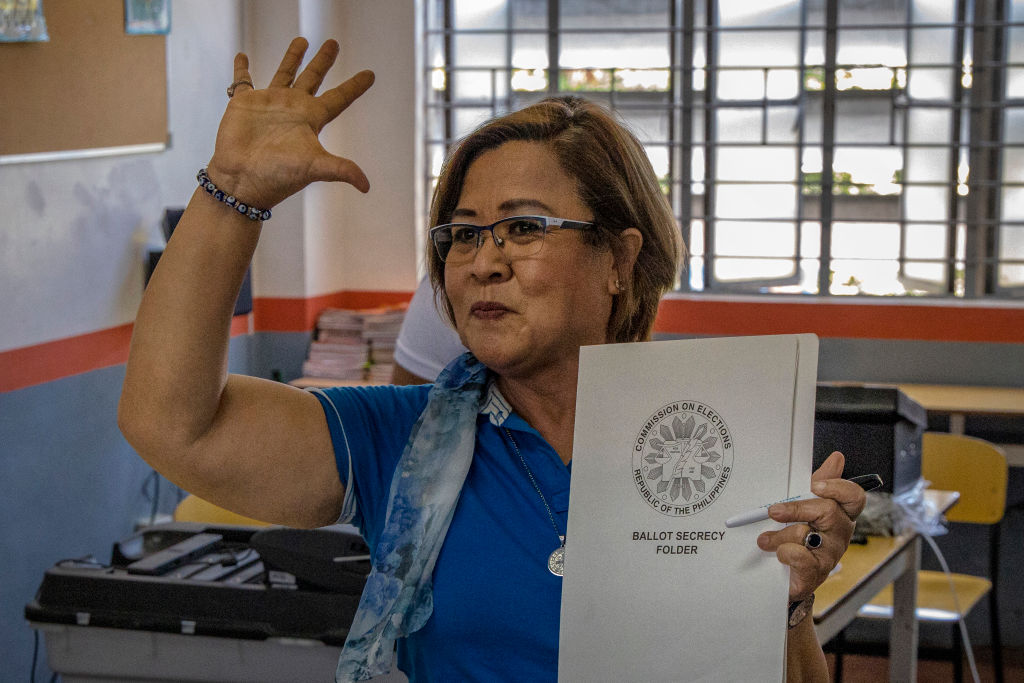

On Friday – two days after the emergency meeting convened by Soliman – Tindig Pilipinas staged a protest outside the building where votes are still being counted, questioning “inaction and mishandling” of the election. It is clear there was vote-buying in the leadup, and there were also technical glitches. Tindig Pilipinas maintained that these irregularities “raise questions on the integrity of the elections and cast doubt on the results.”

But behind the scenes, the group acknowledges that even if the result lacks integrity, the tide of support for Duterte is undeniable, and there seems to be no clear way forward for those seeking to peg it back.