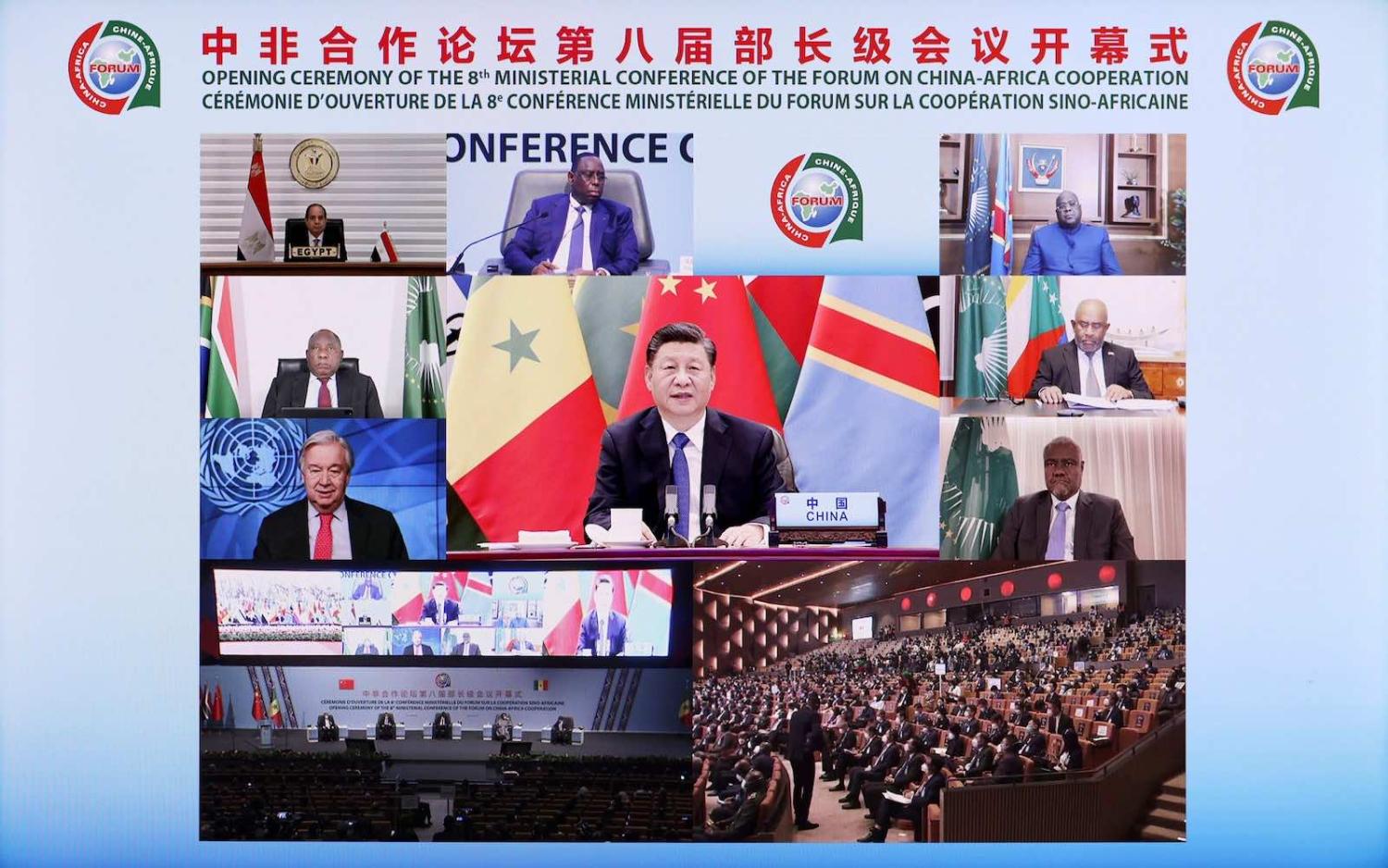

From 29–30 November, the eighth edition of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) was held in Dakar, Senegal, bringing together the foreign ministers and high-level attendees from African countries and China. This year’s theme was to “Deepen China-Africa Partnership and Promote Sustainable Development to Build a China-Africa Community with a Shared Future in the New Era”.

FOCAC is a tri-annual meeting launched by China in 2000 to project and coordinate Chinese foreign policy and cooperation objectives in Africa through commitments in consultation with African leaders. Previous meetings were held in Beijing (2000, 2006, 2012, 2018), Addis Ababa (2003), Sharm-el-Sheik (2009), and Johannesburg (2015). This latest meeting was the first FOCAC to have been hosted by a West and francophone African country, cementing China’s presence in a region that has traditionally attracted less Chinese attention compared to other regions in Africa.

The forum adopted four resolutions: The Dakar Action Plan (2022–24); the 2035 Vision for China-Africa Cooperation; the Sino-African Declaration on Climate Change; and the Declaration of the Eighth Ministerial Conference of FOCAC.

This latest FOCAC underscores the extent to which China views the African continent as an aggregate of countries within a long-term Chinese strategy for increased geopolitical influence and economic growth.

Speaking by video link from Beijing, President Xi Jinping announced an additional 1 billion doses of Covid-19 vaccines to Africa and pledged $40 billion in financing focused on fostering economic growth. The financing was less than that pledged at previous FOCACs but doesn’t mean China is disengaging from Africa. Rather, it reflects a change in China’s approach from large and expensive state-financed infrastructure projects towards the encouragement of more targeted investments from a variety of actors in a broader range of sectors.

Xi also outlined priority areas for the next three years, listing health, agricultural development, trade promotion, investment promotion, digital innovation, green development, people to people exchanges, and peace and security. Some of these are traditional pillars of Sino-African cooperation, while others suggest a shift in priorities.

The forum’s emphasis on green development and dissemination of the first ever Sino-African Declaration on Climate Change signals Chinese intent to lead on climate change mitigation and adaptation in Africa. Investment promotion is not new, but an emphasis on state-supported private sector investment is. We can expect to see more public-private partnerships, private investment promotion, and Chinese firms venturing into Africa, perhaps through Chinese government regulatory incentives.

Lastly, China’s emphasis on digital innovation in Africa is a natural outgrowth of its strong track record in building the continent’s digital infrastructure. China also announced the establishment of a cross-border RMB center to increase the use of the yuan in trade.

Notably missing was a substantive discussion or serious acknowledgement of the debt issue being faced by many African countries who struggle to repay or renegotiate their loans with China.

Given the urgency of post-Covid recovery, the meeting was a good opportunity for African leaders to publicly raise thorny issues and demonstrate solidarity with one another. Countries who hold resources vital to China’s economic growth, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or others who enjoy “comprehensive strategic partnerships” with China such as Algeria, Egypt, and South Africa, could have taken the lead. This suggests that the hope, expressed by many China-Africa commentators, that African states would use the forum to leverage their collective clout and advocate for more equitable and inclusive relations with China did not materialise.

This apparent reluctance is partly due to the structure of FOCAC, which serves as a platform for announcements while specific deals are negotiated bilaterally. Yet it is also due to the centrality of state elite relations in the Sino-African relationship overall, and a lack of will on their part to deviate too much from the status quo that benefits them. This year’s FOCAC included all 55 members (53 African countries plus the African Union and China), highlighting the fact that, as during previous FOCACs, more African leaders chose to attend FOCAC than the United Nations General Assembly in September.

Above all, this latest FOCAC underscores the extent to which China views the African continent as an aggregate of countries within a long-term Chinese strategy for increased geopolitical influence and economic growth, and that it is sticking to its game plan.

In her welcome speech, Senegal’s Foreign Minister Aissata Tall Sall suggested that China do more to help address the growing insecurity in the Sahel; this appears to have gone unheeded. Nonetheless, Sall spoke up. If African elites or civil society want their countries to have more equitable relations with China, they need to harness opportunities to say so, especially during high-profile events such as FOCAC when international attention is on China-Africa relations.