Two-and-a-half centuries ago, Saxony and Brandenburg were two of Central Europe’s great powers and rivals. Even today, in their more modest post-1990 incarnations as German federal states, they continue to evince vastly different identities. Centred on the historic cities of Dresden and Leipzig, Saxony is brimming with pride for its rich cultural past, while the poorer and more sparsely populated Brandenburg, with its capital in Frederick the Great’s Residenz city of Potsdam, forms the sleepy, provincial hinterland of Berlin.

But as former territories of the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, the respective politics of Saxony and Brandenburg have a great deal in common. Their political imaginations are more likely to be filled with thoughts of Poland and Russia than of France, Britain, or Brussels. More significantly – and this they share with other regions of Germany’s East – at least as many Saxon and Brandenburg voters place their faith in the political extremes as in the traditional parties of centre-left and -right.

And on Sunday, both Saxon and Brandenburg went to the polls for the first time since 2014, an era in German politics that has been dominated by themes of immigration and identity politics.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, much discussion in the lead-up to Sunday’s polls centred on whether the upstart far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), for the first time in its history, would become the largest party in any one of Germany’s 16 constituent federal states. This did not come to pass, despite its historic results of 27% in Saxony and 23% in Brandenburg. In Saxony, the vote of the ruling Christian Democratic Union (CDU) held up, as did that of the Social Democrats (SPD) in Brandenburg.

Despite this, however, the news was mixed for the CDU and the SPD – Germany’s traditional “People’s Parties” (Volksparteien). While the CDU’s 15% in Brandenburg was a record low in that state, never in the history of post-war Germany has the SPD fallen to a vote as low as the 7.5% it drew in Saxony. The results were yet another affirmation of the precipitous recent decline of the Volksparteien in the face of the far-right and – though more modestly in the East – a resurgent Green Party.

It is proving to be something of a vicious cycle. Disaffection breeds division, but division in turn cultivates greater disaffection.

But the CDU and SPD have not been supplanted by their challengers; the effect has not been the creation of new “People’s Parties”, but rather an increasing fragmentation of the German political system. The results from Saxony and Brandenburg, then, continue an irresistible drift in this direction. While the leading parties of the two states will remain unchanged, their governing coalitions will likely have to expand from two parties to three. The disintegration of the old party system is utterly indicative of a phenomenon that is afflicting European national politics all across the continent.

And, most worryingly, it is proving to be something of a vicious cycle. Disaffection breeds division, but division in turn cultivates greater disaffection. Escaping from this cycle requires a breadth of vision and reserves of courage that Germany’s old parties – not to mention its Chancellor – conspicuously lack.

The rise of the AfD is symptomatic of the much more general problem at hand. Its electoral successes in Saxony and Brandenburg have rendered the formation of governing coalitions more difficult. All other parties have excluded the possibility of coalition talks with the far-right. Their supporters have little sympathy for the AfD, a reality that in turn nourishes the circled-wagon mentality with which the far-right energises its base.

But is this a mistake? Might the key to defeating insurgent populists in fact be to concede to them the responsibilities of power and thus taint them with the ignominy of compromise?

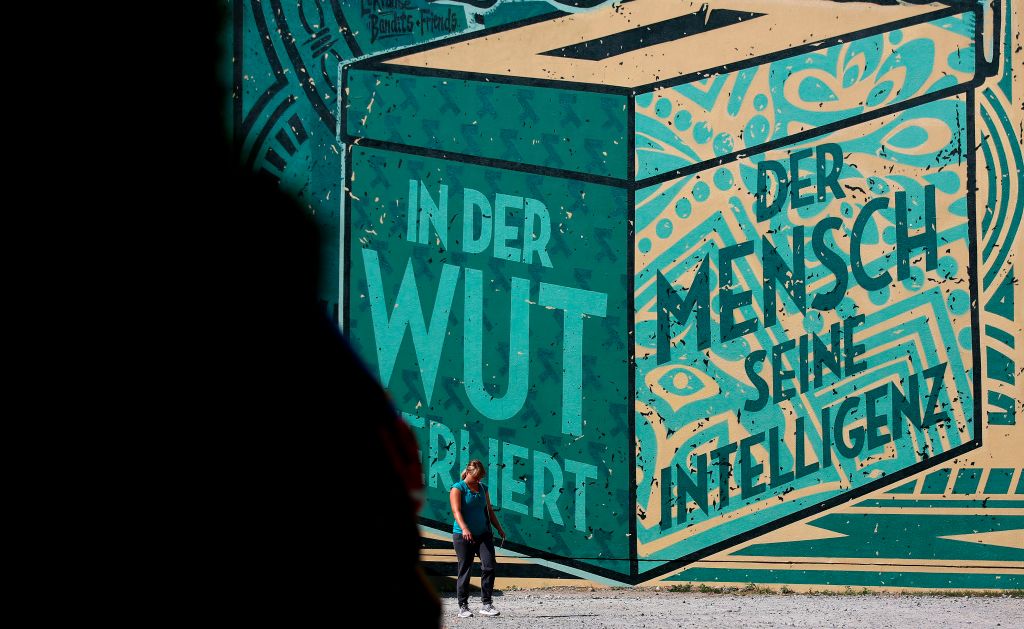

There is some superficial appeal to this strategy. After all, the AfD revels in the attention it attracts. It is fuelled by outrage, which it propels and attracts in copious measures. Its leaders project themselves as engaged in a revolutionary crusade. The AfD, in other words, is a party of process, not of outcome – a movement rather than a party as traditionally conceived. As such, some of its opponents believe that the tedium of power would deprive it of its revolutionary energy.

What’s more, now might be an opportune time to test the AfD’s credibility as a key player in German politics. The party’s adolescent growth spurt seems to be over, prefiguring a new age of maturity. During the volatile years of 2016–17, it multiplied its numbers of supporters, especially in the East. But while it can now claim a passionately loyal base, it seems to have reached a ceiling in 2017, plateauing at about 13–14% nationally, and somewhere between 20% and 25% in the East.

This is not an insignificant number, to be sure, but its steadiness must portend a new set of medium- and long-term electoral strategies. The leadership itself is divided on the question of whether it wants the AfD to be a party of protest or a party of government. Exploiting this cleft, some opponents optimistically believe, might just be the way to sow disillusionment among its populist base.

But it is a strategy fraught with danger. Any party that ventures a coalition with the AfD risks alienating its own base, further compounding the threat of fragmentation. And – as the efforts of the Christian Social Union in Bavaria last year demonstrate – simply aping the populists in an effort to attract their supporters has much the same effect. But above all, short-term political strategies hardly help to address the underlying resentments that propel the extremists and the populists: if anything, the more short-term the thinking, the more self-defeating it may prove.

Dark clouds are gathering on Germany’s horizon, conferring upon this problem a particular urgency. At the federal level, the SPD – Chancellor Angela Merkel’s junior coalition partner – is presently occupied with selecting its new leader, following the resignation of Andrea Nahles in June. Should the new leadership claim a mandate to pull the rug from under Merkel’s feet, a federal election may come sooner rather than later – and at a time when Germany appears to be sliding into a recession.

Any such election would likely fragment the political spectrum even more, making the formation of any new coalition considerably more difficult – perhaps even impossible. Political fragmentation may well be the last thing that Europe needs at the heart of its biggest economy. But should things continue as they are, it is something of which we will likely see more, not less.