Outside observers have all but given up hope that China will engage in meaningful state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform. There is a pervasive sense that rather than shrinking SOEs, China’s leaders are committed to increasing their prominence within the economy.

Foreign perceptions of Chinese SOEs were not always so pessimistic. In the 1990s and early 2000s, China engaged in a massive campaign of SOE reform, creating hope that China might be on a path towards a less state-centric economy. SOEs began to look less like government bureaucracies and more like companies, adopting modern governance structures and targeting improvements in efficiency and profitability. During this period, private companies became a dominant source of output, investment, and employment in the economy. The Chinese government appeared to be willing to allow the private sector to displace SOEs in many key areas of the economy.

Hopes and expectations for more grand reforms were slowly extinguished during the 2000s. The Chinese government seemed content to coast on previous successes. The pendulum shifted towards tightening as the government created new bodies such as the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council, to centralise its control over large SOEs. As reform stalled out, the convergence in productivity between SOEs and private companies came to an end in 2007 and then began reversing. Whatever motivation remained for SOE reform was further weakened by the global financial crisis, as China plowed ahead while more market-driven economies struggled to recover.

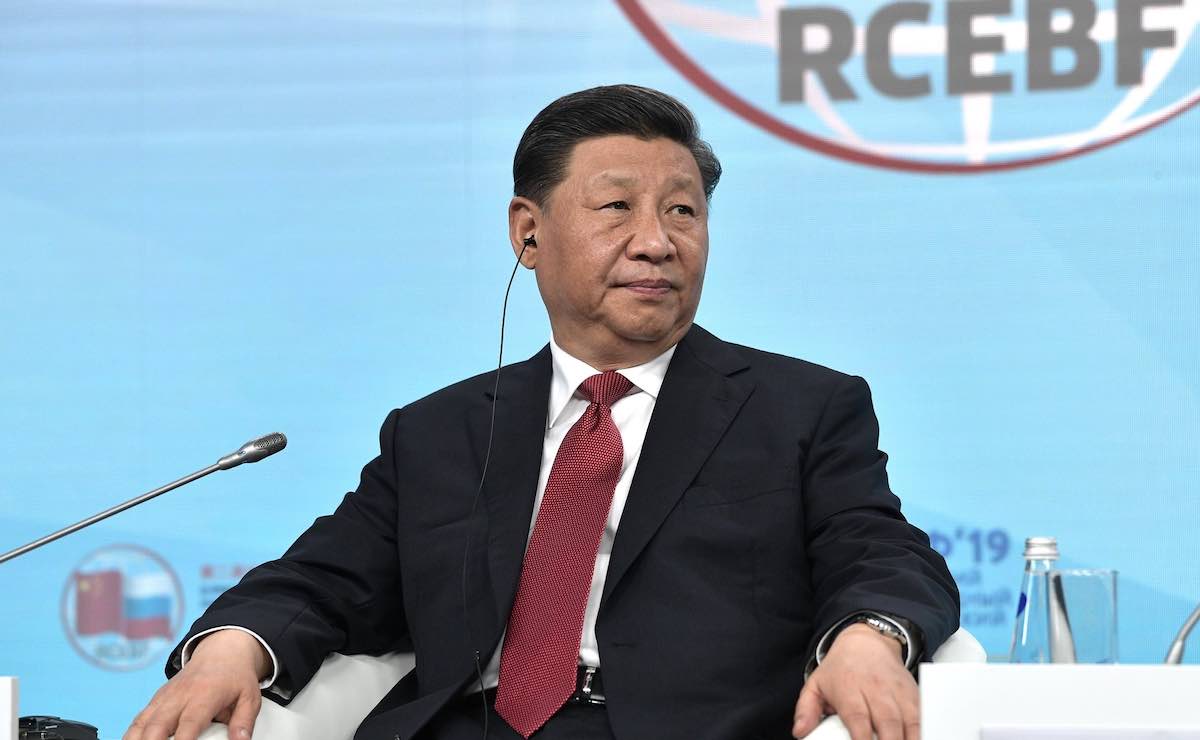

The Xi Jinping era

The rise of Xi Jinping and his consolidation of power have coincided with an even stronger impetus to strengthen the role of SOEs. Xi’s embrace of SOEs stems from a belief that they can advance his goals of strengthening the Chinese Communist Party and reclaiming China’s former national greatness. In the Xi formulation, SOEs play a special role within the economy, providing public services, stabilising the economy during periods of volatility and supporting government industrial policy and other initiatives.

The lack of transparency around SOEs has contributed to growing levels of distrust, both within and outside of China, about the government’s intentions.

Instead of allowing failing state-owned firms to shut down or be displaced by private competition, the approach during the Xi years has been an even greater emphasis on mergers between state-owned firms. As a result, some truly enormous state-owned conglomerates were established in recent times.

The Chinese government has also doubled down on using SOEs as a tool for the implementation of government policy. State-owned firms have been at the forefront of the Chinese government’s drive to develop domestic sources of key technologies, such as semiconductors. SOEs have participated in thousands of projects under the banner of the Belt and Road Initiative. When the spread of Covid-19 in early 2020 forced the Chinese economy into a severe lockdown, SOEs emerged as the economic engine of last resort, spending and investing while private firms pulled back.

Impact on foreign businesses and investors

While SOEs only account for around 25% of the Chinese economy, they occupy many of the commanding heights of the economy. SOEs are dominant in key industries, including energy, aviation, finance, telecoms and transportation.

The ability of foreign businesses to compete within these sectors is either limited formally by law or constrained through the monopolistic position of SOEs. Furthermore, SOEs continue to benefit from implicit guarantees of government support, allowing them access to cheaper financing than would otherwise be available.

SOEs also play a disproportionately large role in China’s equity and bond markets. Listed SOEs account for 40% of the market capitalisation of Chinese companies and have raised more than US$90 billion in new equity from investors since 2015. In the bond market, state-owned issuers account for the majority of total bond issuance. Even if they avoid investing directly in SOEs, foreign investors must contend with the ability of the government to strongly influence the market. The government mobilised state funds – the so-called national team – to stabilise markets during periods of turmoil and several prominent private companies have received large bailouts from state-linked investors.

Getting reform back on track

The lack of transparency around SOEs has contributed to growing levels of distrust, both within and outside of China, about the government’s intentions. Despite declarations by the Chinese government that it is committed to competitive neutrality, private and foreign enterprises in China continue to cite a litany of disadvantages they face relative to SOEs. The government has also trumpeted the injection of private capital into SOEs, the so-called mixed-ownership reforms. However, the SOEs that have undergone this restructuring seem to have changed very little in practical terms.

China’s stated goals for SOE reform are sensible: separating ownership and management, reducing interference in day-to-day operations and allowing SOEs in competitive sectors to restructure and operate along market lines. Unfortunately, the implementation of these reforms has been plagued by poor communication, limited transparency and weak follow-through.

SOEs are here to stay and will continue to generate tensions between China and the rest of the world. However, if China can adopt a more rules-based and transparent approach to managing SOEs, it may mitigate some of these concerns and help its economy in the process.