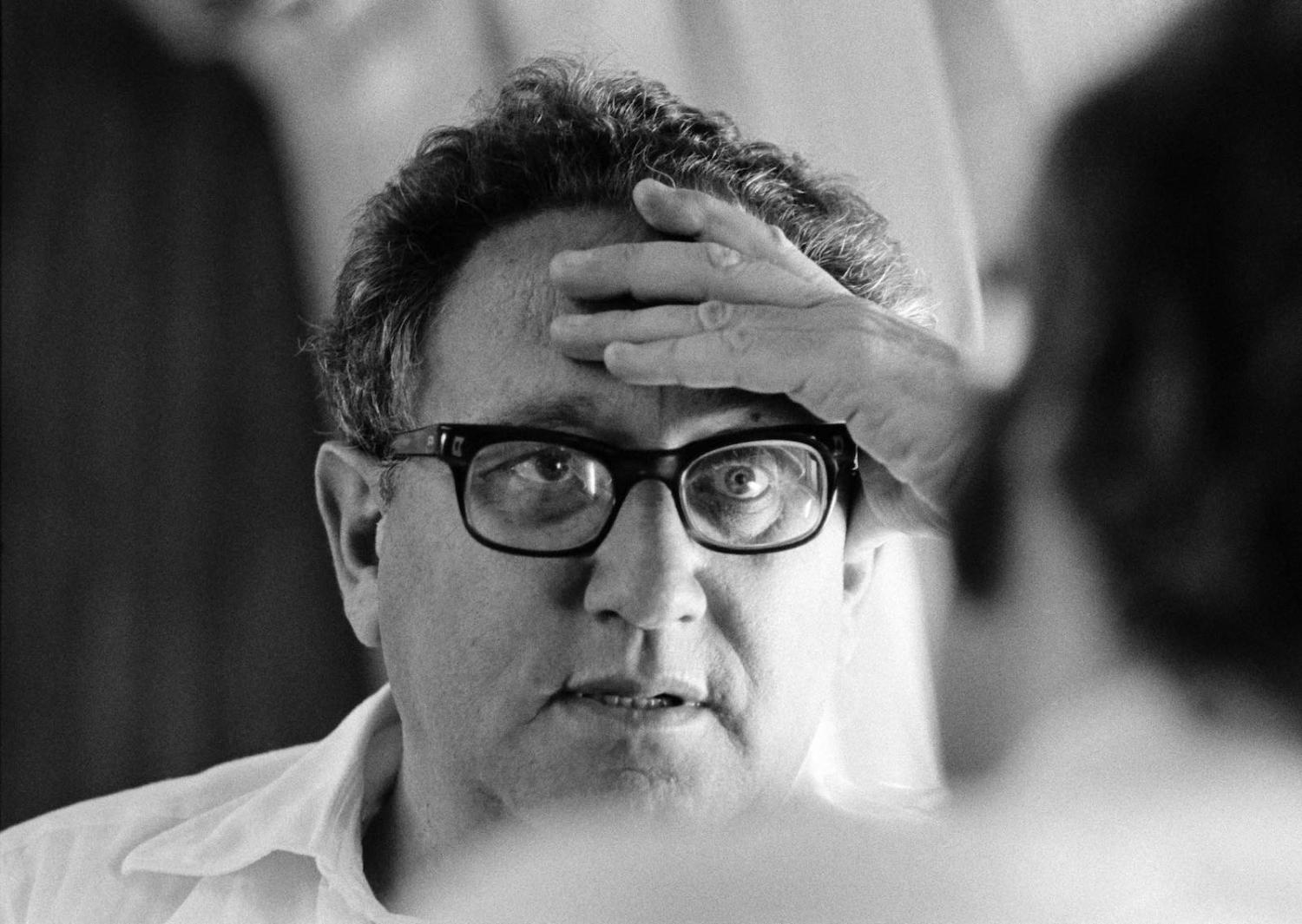

Few people today can recall the time when Henry Kissinger conceived and executed America’s foreign policy as National Security Adviser and Secretary of State between 1969 and 1977. But what he did then – and not his long decades on the sidelines since – is what counts in assessing his career.

So, it’s important, and instructive, to go back and look at that time, following his passing at age 100. I’ve found, a little to my surprise, that the closer one examines Kissinger’s record in office during those years, the better he looks. Indeed, one can argue that he was, in his strange partnership with Richard Nixon, the most effective and important American statesman since the remarkable generation of Wise Men that launched America into the post-war world.

To understand that achievement, we need to recall the circumstances. When Kissinger first went to work for Nixon in 1969, America faced an acute foreign policy crisis. The country’s power seemed to have slumped lower that at any time in the 20th century, and the global order that it had laboured to create appeared to be dissolving.

His perspective was closer to that of traditional European great powers, all too aware of the other great powers that surround and challenge them.

It is easy now to downplay this sense of crisis, because we know how things turned out, but the problems then were very real, and the outcomes far from certain. It is at least arguable that Kissinger’s achievements in office – detente and arms control with the Soviets, withdrawal from Vietnam, the management of Middle East crises, and of course the opening to China, among others – made all the difference.

Kissinger never shared the breezy confidence in American preponderance that has been so characteristic of his adopted country. He focused instead on the limits of America’s power, and the need accordingly to set realistic aims and pursue them economically. His perspective was closer to that of traditional European great powers, all too aware of the other great powers that surround and challenge them.

Perhaps, then, he did more than anyone else at the fulcrum of the Cold War to stabilise the global order and re-establish American power. If so, he laid the foundations for the successes of the 1980s, culminating in the end of the Cold War. And if that is right, he deserves a large share of the credit for what happened a decade and more after he left office.

There are many reasons why this is not generally acknowledged, including, of course, his connection with Nixon. But – perhaps more importantly – he was always an outsider, and this was crucial to his success.

It has often been remarked that Kissinger’s approach to international affairs was deeply rooted in European rather than American ideas of both the purposes and methods of statecraft. But it is worth looking more deeply at what that meant and how it worked when he took high office at such a demanding time.

The best place to start is with A World Restored, the first of two books he published in 1957 and still well worth reading today, especially the first and last chapters. In it, Kissinger used the 1814-1815 Congress of Vienna and the role of Klemens von Metternich as case studies in statecraft, and in particular to argue that the true objective of statecraft should be to establish or preserve order, rather than to seek improvement – to keep things stable, rather than make them better.

Kissinger modelled himself on Metternich, who saved Austria and rebuilt the European order in 1815 by seeing more clearly than others what was needed.

This did not make him a crude Morgenthau realist, because he was concerned with order, rather than with power for its own sake, but it did set him against the Wilsonian tendency to see America committed to making the world a better place. Moreover, his thinking about the problems of order in the post-war world were framed by a European rather than American attitude to power. It was this perspective that made Kissinger so suited to managing the crisis of American power that confronted him in the years after 1969. To a remarkable degree, the times suited him.

In meeting this challenge, Kissinger modelled himself on Metternich, who saved Austria and rebuilt the European order in 1815 by seeing more clearly than others what was needed, and working more artfully to bring it about. It is easy to smile at Kissinger’s heroic ego, and to note how far he himself often fell short of the Metternichian ideal of statesmanship that he describes so vividly in A World Restored.

But it is more striking how far Kissinger succeeded in following Metternich’s example. Like Metternich, Kissinger did see more clearly than many others what was needed in the early 1970s to escape and recover from the disaster of Vietnam, stabilise the Cold War, and redefine a sustainable US global posture.

But he also displayed Metternichian levels of craft and guile, both at home and abroad, in attaining his ends. Sometimes this was admirably adroit and effective, and at other times it was not just brutal but unnecessarily so. He received, and deserved, a lot of criticism for that. Much of it was directed at his polices on issues that were sideshows to the Cold War – Bangladesh, Chile, East Timor and Cyprus, for example. That’s not to say that Kissinger’s policies and their consequences were unimportant, but they loom as large as they do today partly because the Cold War itself was managed towards the remarkably benign outcome of 1989, for which Kissinger deserves a lot of the credit. So there is a lot of good to set against the acknowledged bad in his record. Many of Kissinger’s most vocal critics – Christopher Hitchens for example – have little standing to censure Kissinger’s choices. Hitchens thought invading Iraq was a great idea.

The most serious questions about Kissinger’s judgments relate to his attitudes to the use of force. Like his hero, Kissinger always saw war purely as an instrument of statecraft, and he forever sought to tame war to the demands of diplomacy. In one of his most famous early books, Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy, Kissinger tried to update 18th-century statecraft by explaining how nuclear war could be limited and controlled to fit diplomatic agendas.

Likewise, he viewed the 1970 Cambodian incursion and the 1972 Christmas bombings of North Vietnam as diplomatic manoeuvres. But, of course, they were much more than that. He never quite saw that war always has a logic and dynamic of its own, and is hard to tame. These were very serious mistakes.

Nonetheless, Kissinger’s achievements in office remain impressive. What has American foreign policy achieved in the last 25 years, when American power has supposedly been so great, to compare with what Kissinger managed in his eight years in the White House?

There is, though, no doubt that America today needs someone of Kissinger’s stamp to conceive and create a sustainable relationship with this powerful rival.

Above all, of course, the opening to China – for which Kissinger must share some credit with Nixon – remains one of the most critical policy shifts in modern history, and it is notable that this is the achievement on which his reputation today rests. We currently live with the consequences of that decision, and managing them is the most critical foreign policy choice America has faced since the end of the Cold War, and perhaps the most complex and demanding since Kissinger’s time in office.

Alas in retirement, despite writing a lot about it, he had little useful to say about this challenge. There is, though, no doubt that America today needs someone of Kissinger’s stamp to conceive and create a sustainable relationship with this powerful rival. No such person seems to be available. With US policy currently in the hands of China hawks who are eager to launch a new Cold War but have no idea how it could be won or why it must be fought, the lack of sober, realistic statesmanship is all too obvious.

There may be a simple reason for that lack, which Kissinger himself identified back in 1957. He opened the last chapter of A World Restored with Metternich’s reaction to the death of his great British collaborator, Viscount Castlereagh. “The man is irreplaceable,” he quotes Metternich as saying. “An intelligent man can make up the lack of everything except experience. Castlereagh was the only man in his country who had experience in foreign affairs.”

It is perhaps a little trite, but also I think probably true, to attribute some of Kissinger’s talents and his success to his experiences – as a Jewish child in Nazi Germany, as a soldier during the Second World War and its aftermath in Europe, and as an engaged analyst of the early Cold War. He understood what a really serious, life-and-death strategic contest was like. His successors are less well prepared. They do not even understand that this is what the new Cold War with China will be like.