China’s promise to treat Hong Kong as “one country, two systems” has been in the spotlight ever since the controversial extradition bill proposed by the Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam in June resulted in massive protests, not only against the bill but also over Beijing’s meddling in Hong Kong affairs. While the protests have been largely peaceful despite the huge crowds – one report suggested as many as two million protesters marched on 9 June – there have been scattered cases of violence as protestors and the riot police fought each other.

As the political chaos in Hong Kong in 1967 proved to be an unexpected gain for Singapore, so it looks to be again in 2019.

This continued political chaos in Hong Kong has only served strengthen the image of another of Asia’s island cites as a stable venue for investment – Singapore.

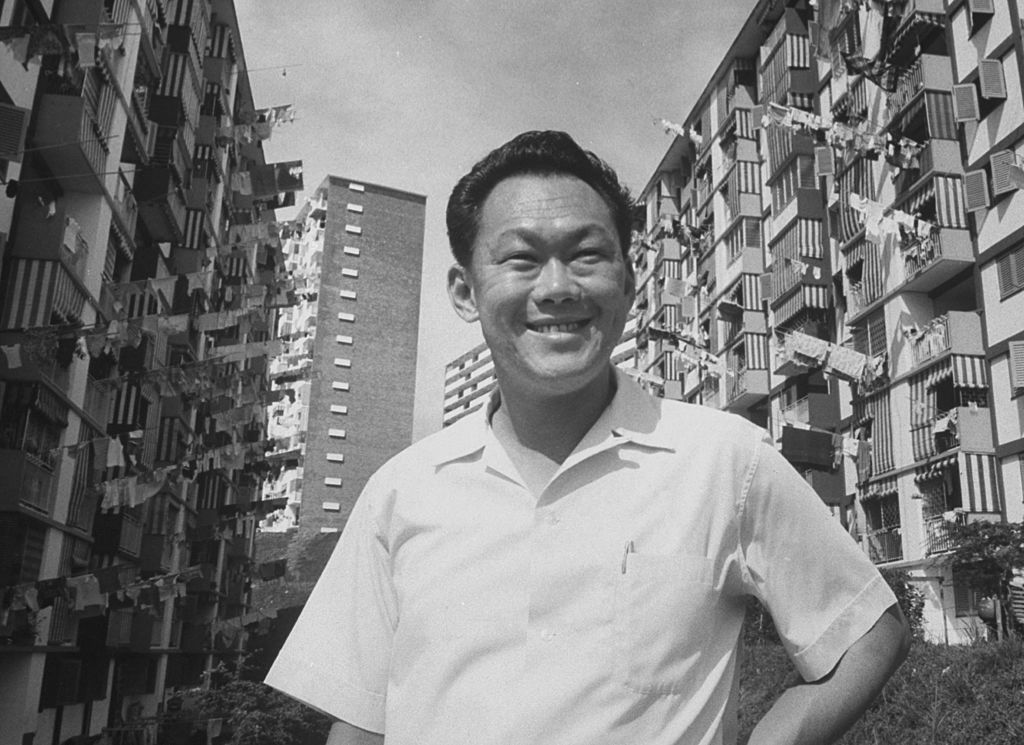

Singapore has benefitted from Hong Kong’s troubles before. Former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew revealed in his autobiography that after seceding from Malaysia in 1965, he made frequent visits to Hong Kong to encourage their manufacturers to establish factories in Singapore.

Lee got his opportunity when riots instigated by pro-communist trade unions occurred in Hong Kong from May to December 1967, resulting in 51 deaths. Students and workers ran through the streets, shouting slogans, assaulting police officers and planting bombs. For the next few months, land values, stock market shares and bank deposits in the then British colony fell sharply. Local entrepreneurs also feared swirling rumours that China would invade Hong Kong. In May of 1967 alone, about HK$800 million was shifted out of Hong Kong by nervous investors.

Only a few years earlier, Singapore had embarked on a rapid industrialisation program. The Economic Development Board (EDB) was formed in 1961 and subsequently worked tirelessly to look for places to build factories for investors from Hong Kong. Then finance minister Goh Keng Swee reported to parliament at the time that in addition to tax incentives and possible citizenship, Hong Kong entrepreneurs saw Singapore as a safer and more stable location in the long term.

Prospective investors from Hong Kong were also impressed with the minimum of bureaucratic red tape since they only had to work with the EDB, which wanted “pioneer industries”. Pioneer certificates were issued to industries that manufactured new products not previously made in Singapore and were exempted from paying the standard 40% tax on company profits for five years or more depending on the size and type of investments. Pioneer industries were also expected to hire at least 200 people in a bid to keep unemployment down. In November 1967, nearly one-third of 44 new companies in Singapore granted “pioneer status” involved Hong Kong capital that had moved to Singapore.

But after the Hong Kong riots ended in December 1967, the drivers for this shift dissipated. By 1970, The Straits Times reported that money flowing to Singapore from Hong Kong “now seems to have steadied down”.

History appeared to be repeating in 2019. The Sun Daily in Malaysia noted the political chaos had hit Hong Kong’s reputation as a stable financial hub, and “its loss might just be Singapore’s gain”. The same paper also noted that Singapore had promoted itself as “a less crowded, more orderly alternative to Hong Kong” with a reputation for a strong rule of law, a criterion in attracting businesses. On 1 July, Channel News Asia reported that some foreign wealth managers were abandoning plans to open offices in Hong Kong in favour of Singapore, and rich Hongkongers had moved funds out of the territory out of fear that their assets might be seized by Beijing.

It wasn’t only the protests over the extradition treaty that was to blame. A survey by Asian Private Banker in 2018 found Singapore was more attractive than Hong Kong because it was “less connected to mainland China from a regulatory, political, and financial perspective”. Economic analysts had also pondered their future in Hong Kong when it was announced in November 2018 that economists in mainland China had to sign a self-discipline agreement to take into account the interests of the Chinese Communist Party when writing their reports. This was said to have had a “chilling effect” on the finance community in Hong Kong as it made analysts’ work more difficult.

As the political chaos in Hong Kong in 1967 proved to be an unexpected gain for Singapore, so it looks to be again in 2019. In 1967, it was the communists in Hong Kong who instigated the riots, leading to an outflow of capital from the colony. In 2019, it was the Chief Executive – long regarded as nothing more than a lackey of the communist government in Beijing – who introduced a bill without public consultation, resulting in mass protests, and potentially another outflow of investment and money from Hong Kong.

While the situation calmed in 1967 after the riots, Hong Kong after 2019 will not be the same again. The Special Administrative Region of China looks ahead gloomily towards the end of “one country, two systems” by 2047 and a future uncertain.