Book review: Indonesia out of Exile: How Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet Killed a Dictatorship, by Max Lane (Penguin, 2023)

Australia’s relationships with Indonesia are usually measured through stories of terror and disaster, aid and trade, rarely anything that’s cerebral.

That’s been corrected by writer Max Lane revealing the richness of Indonesian literature, first through translations and now with fine detail in Indonesia out of Exile – the story of how one persecuted writer killed a dictatorship.

In 1980, Lane was a mid-level diplomat in the Jakarta Embassy with exemplary language skills. These led him to the covertly published Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind) and its three sequels – the Buru Quartet. The books are set when Dutch power was declining and told through the growth of Minke, the son of an elite Javanese family. The character was based on the life of pioneering journalist Tirto Adhi Soerjo (1880–1918)

Lane met the author Pramoedya Ananta Toer (Pram) just out of an island prison and offered to translate.

When Ambassador Rawdon Dalrymple heard a staffer had tapped into Indonesia’s culture, he could have praised the initiative and expanded the project to develop relationships. But diplomacy was driven by fear. Pram’s books were banned. Lane was ordered out.

Shame became gain. “(Dalrymple) did us a great favour,” Lane recalls. Back in Australia, he could negotiate with Penguin to see the book appear in English. Publisher Brian Johns reportedly said it was the best decision he’d ever made.

News of the expulsion promoted the book and Lane’s career as an activist writer. He became founding editor of the Inside Indonesia magazine and later an academic with “a long commitment to trying to familiarise the Australian community with Asia, and especially Indonesia”. He’s currently Visiting Senior Fellow at Singapore’s Yusof Ishak Institute of Southeast Asian Studies and lives in Yogyakarta.

In Indonesia in Exile, Lane now tells the inside story of how – for more than three decades – a repressive regime controlled the way history was learned: ban the books, maltreat authors and teach lies.

Indonesia has never won a Nobel Prize. The closest moment came with the nomination of the novels of Pram, who spent 14 years in jail, first under the Dutch colonialists, then the Orde Baru (New Order) of autocrat General Soeharto, whose regime was supported by Australia and the United States.

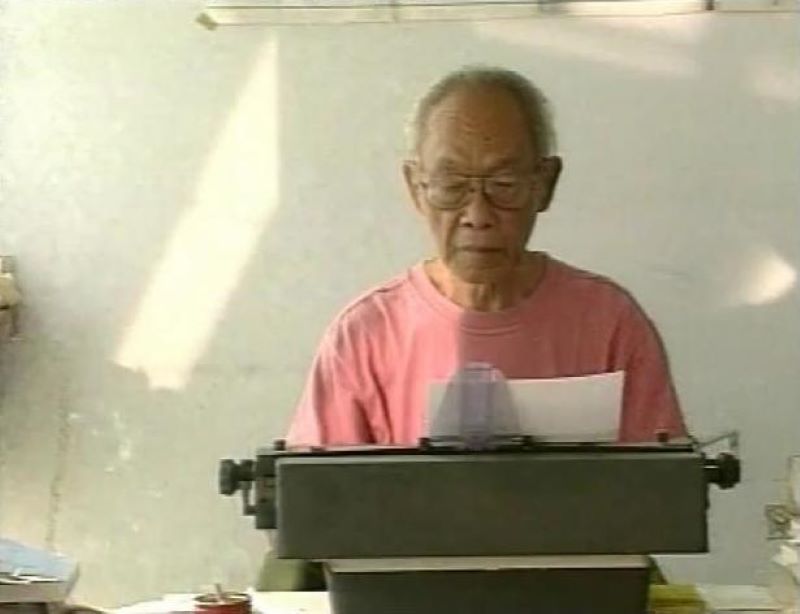

In his youth, Pram (1925–2006) wielded a typewriter in the revolution that created modern Indonesia. After the 1965 coup, his crime was to be a teller of tales about the struggles for national identity divorced from the military version.

The redactors could have countered with stronger stories but flunked the challenge and turned to brutality. Pram and 13,000 other creatives and intellectuals were transported to the wild and remote island of Buru. Here among barbaric guards, disease, hard labour and malnutrition, Pram composed his works, smuggling the pages out to friends in Jakarta, often through church visitors.

Indonesia out of Exile tells of the Hasta Mitra (Hands of Friendship) trio of Pram, publisher Joesoef Isak and journo Hasjim Rachman. Google their names, admire their courage to risk bringing the books into the people’s hands.

When Lane’s translation was in UK, Singapore and Australian bookshops, where it made the Top Ten Bestsellers list, it couldn’t be openly bought in Indonesia, yet 10,000 copies changed hands in two weeks.

Pram was ahead of his time by creating a cast of strong women such as Nyai Ontosoroh, the uneducated concubine of a Dutch planter who runs the business, and their daughter Annelies. She marries Minke in an Islamic ceremony unrecognised by colonial law.

Lane writes that the female characters have “been forged out of their resistance to their oppression as women”. They inspired Lane’s wife Faiza Mardzoeki to take her play They Call Me Nyai Ontosoroh to Holland.

This Earth of Mankind has been published in 33 countries. For most buyers, it’s been their first encounter with Indonesian literature – or the country outside tourist brochures. Overseas readers got to understand the rising emotions and actions of colonised people demanding their rights to live their lives, their way.

Book ban laws were scrapped in 2010. In 2019, a three-hour Indonesian movie Bumi Manusia, excited nationalists and romantics, though not cinephiles.

UNSW Professor David Reeve writes that Lane’s book “explains how and why Indonesia is as it is today and how it might become what Pramoedya hoped”. That was “Indonesian national awakening” yet the word “Indonesia” never appears in 1,500 pages of text across the books. Writes Lane:

(The Hasta Mitra trio’s) love for Indonesia was the love of a generation who saw the new national community being created. The secret of Bumi Manusia is that Indonesia is not present in / on this earth of mankind.

Canberra focuses on Indonesia through the economy, resources and security. But Lane puts his money on the people, the “real internationalisation” of Bumi Manusia and Pram becoming a household name.

Lane doesn’t strut his considerable achievements across half a century. But if his vision proves right, all credit to a reflective Australian for promoting a prophet admired by the world when without official honour in his own land.