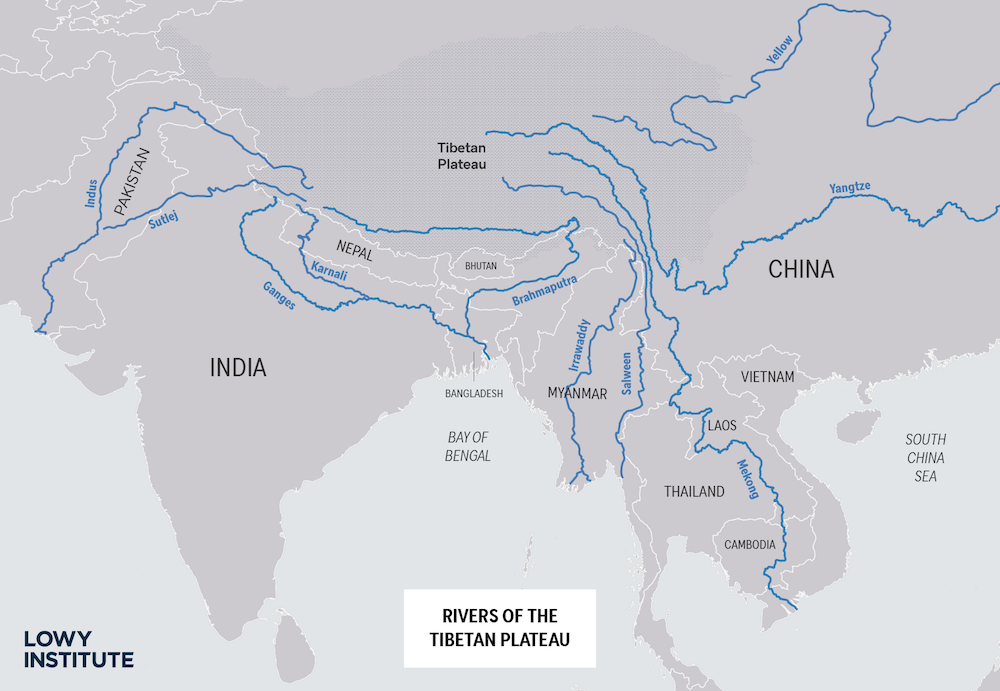

Transboundary river governance has long been a headache for governments in Asia. One of the region’s most complex cases is the bilateral governance of the Yarlung Tsangpo-Brahmaputra by China and India, rival rising powers with enormous populations and competing water demands.

Originating in the Tibetan Plateau in southwest China, the river flows 2,900 kilometres across southern Tibet via the Himalayas, entering India through Assam and Arunachal Pradesh (South Tibet), where it is called the Brahmaputra.

For India and China, the Brahmaputra is essential to socioeconomic development. For India, the river accounts for nearly 30 per cent of the country’s freshwater resources and 40 per cent of its total hydropower potential. For China, the Brahmaputra’s role in the country’s total freshwater supply is limited but plays a significant role in Tibet’s agricultural and energy industries. Despite China’s basin coverage, it only contributes between 7 per cent to 30 per cent of the total basin discharge.

Even though the river is important to both countries, bilateral collaboration remains fragmented and limited, mainly concerned with hydrological data-sharing. In 2002, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed between the two countries to share hydrological data on the Brahmaputra during the flood season. It has been twice renewed (in 2008 and 2013). Another MoU, signed in 2013, aims to strengthen Sino-Indian water governance cooperation on cross-border rivers for issues such as emergency management.

Although these agreements suggest China and India seek to cooperate, bilateral water governance remains largely influenced by broader geopolitics and rivalry. Notably, China refused to share hydrological data with India during the 2017 Doklam standoff between the two militaries in the Himalayas.

One area of Sino-Indian competition that influences bilateral water governance is the construction of competing water infrastructure projects on the shared river. Each country has accused the other of hydro-hegemonic behaviour through hydropower dam construction.

In recent decades, China has built numerous dams on the upstream of transnational rivers in Tibet, including 11 built and/or planned hydropower dams on the Brahmaputra. As dams can affect a river’s flow and course, the construction has unsurprisingly caused alarm in downstream India.

On the one side, it is true that China, as the upper riparian, can make decisions that have a direct impact on the quantity of water available downstream. India’s fears are heightened by the fact that China, Asia’s “upstream superpower”, does not have an independent transboundary river policy. Instead, China manages transnational rivers instead as part of its foreign policy. New Delhi also remains sceptical about Beijing’s insistence that the dams are for hydropower generation.

Yet from the other side, China’s contribution to the total river flow is small, meaning that attempts to alter the flow of the Brahmaputra are unlikely to affect India’s water supply. Others also argue that New Delhi encourages the “Chinese hegemony” narrative to defend its own hydropower development projects on shared rivers, which have received significant criticism. For example, India’s Pakal Dul hydropower facility, is built on the Marusudar river, the largest tributary of the transboundary Chenab River, which crosses from India into Pakistan. Observers note that the hydropower facility will improve India’s energy security at the expense of reducing Pakistan’s ability to build similar facilities on its side of the border.

While China is criticised for refusing to sign an independent transboundary river policy, most of China’s downstream neighbours, including India, have not signed one either. Furthermore, China abides by the 1997 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses (UNWC), even if it is not a signatory.

In contrast, questions remain about India’s adherence to the Convention. India’s water-sharing treaties with neighbours such as Nepal and Pakistan have been criticised for significantly favouring India and disadvantaging the other signatories.

Another factor influencing Sino-Indian relations and water governance is the border demarcation disagreements. Without an official mutually agreed border between the two countries, both assert competing claims to territory – Arunachal Pradesh State/South Tibet – in the Eastern Himalayas. These claims are connected to respective assertions of sovereignty. If China abandons its claim to South Tibet/Arunachal Pradesh State, Beijing’s claim of sovereignty over water-rich Tibet will weaken. India, for its part, is unwilling to cede the land to its rival as the territory is the site of China’s victory against India during the Sino-Indian War in 1962.

Amid an increasingly complex and fractured geopolitical environment, continued Sino-Indian tensions over river governance could become a major driver for broader tensions in the region. As river governance and related issues remain unaddressed, worsening Sino-Indian relations and increased rivalry add challenges to sustainable river basin governance.

To address these concerns and reduce geopolitical tensions and resource conflict fears, Beijing should abide by existing bilateral agreements with New Delhi. Potential for preventative diplomacy that supports mutual trust and joint cooperation between India and China, such as between scientists and researchers, should also be encouraged. This will help avoid further complicating an already tense bilateral relationship.