The threat of wealthy countries hoarding vaccines for themselves and denying access to smaller and poorer countries has become the world’s primary cooperative concern. Yet how vaccine nationalism also attaches itself to pre-existing relationships between countries may become another part of this equation.

As vaccines have become the new diplomatic currency, India’s position as the world’s vaccine superpower is providing it with a foreign policy tool that now exceeds its power by traditional metrics.

India produces about 60% of the world’s vaccine output in normal times, with the Pune-based Serum Institute being the dominant manufacturer. There is no solution to this pandemic that doesn’t have India as a central player. India obviously has an enormous domestic need for vaccines, but despite this it has used its capability wisely to donate doses to neighbouring and Indian Ocean countries: Bangladesh, Mauritius, Myanmar, Nepal and the Seychelles.

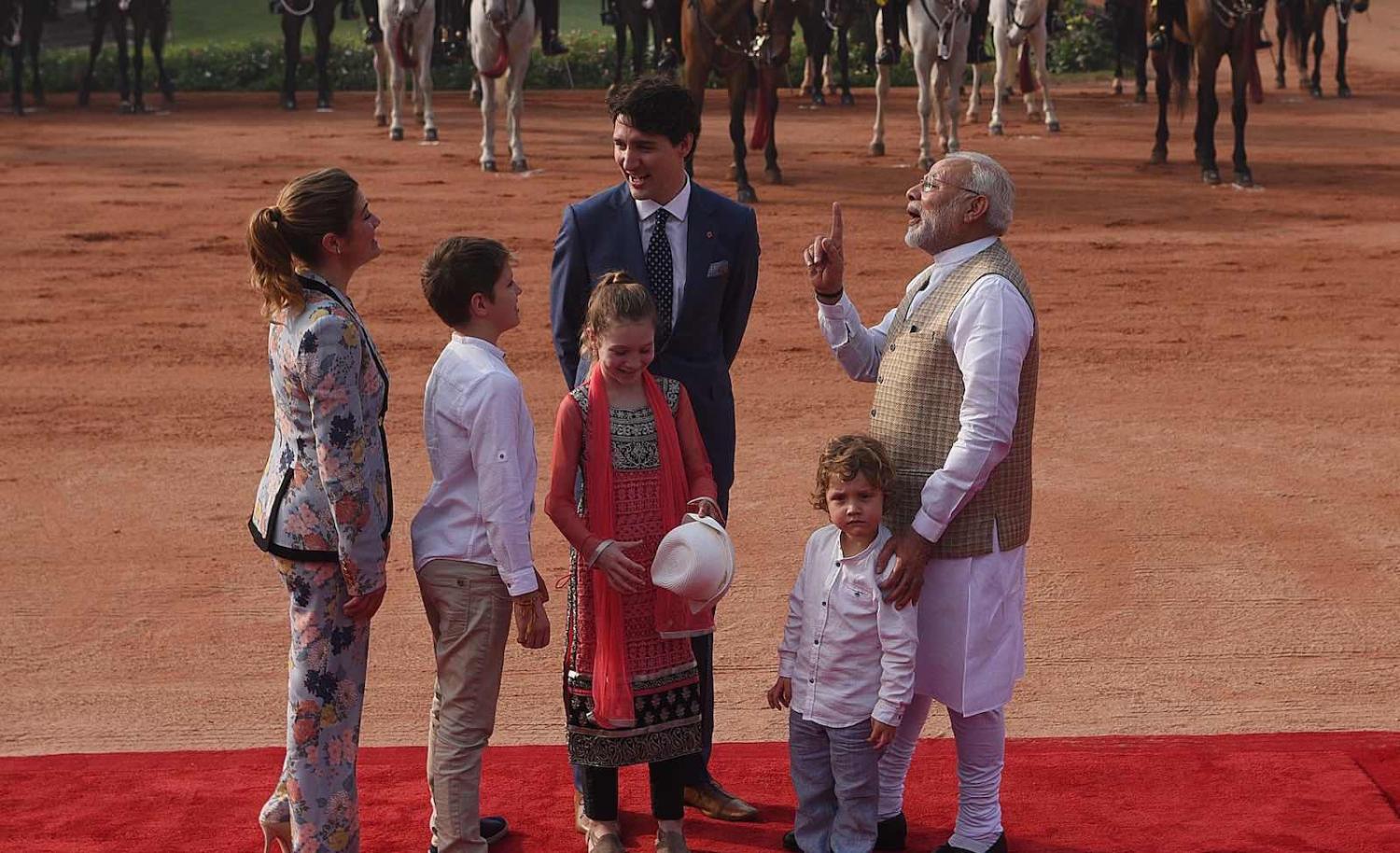

Yet a recent phone call between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau revealed that India’s powerful new instrument also provides it with influence over wealthy Western countries, a striking example of how this other strain of vaccine nationalism might materialise.

Although India and Canada are friendly countries, there is a permanent thorn in the relationship that consistently irritates New Delhi.

Due to a complex web of events, Canada lacks the capabilities to manufacture Covid-19 vaccines itself, leading it to scramble to secure a consistent supply from foreign sources. Initially Ottawa had done well procuring vaccines and administering their rollout, but in recent weeks, supply hit a wall. In terms of vaccines administered per 100 people, after initially being one of the leading countries, Canada has now dropped to 47th in the world. This has led to some embarrassing vaccine sub-nationalism, with Manitoba province circumventing the federal vaccine supply program and securing its own source.

Trudeau sought out Modi to ask if Canada could buy vaccines. Modi responded that India would “do its best” to fulfil Trudeau’s request, language that indicated the leverage India now has, but also left enough wiggle room should Modi choose otherwise. Last week, the Ministry of External Affairs India approved the export of vaccines to 25 countries, as they are subject to export controls. Trudeau’s request came too late to make the list, and while diplomatic calculations will continue to be built into the process, the Serum Institute’s CEO has stated shipments to Canada would be made by the end of the month.

But in the meantime India’s nationalist press have been revelling in the imagery of the phone call, of a desparate Trudeau going cap in hand begging Modi for help. Although India and Canada are friendly countries, there is a permanent thorn in the relationship that consistently irritates New Delhi: India believes that Canada is harbouring Sikh separatists, and Canada cannot stop giving India the impression that this is true.

Issues of national security are, of course, hypersensitive, but there is no longer any serious movement inside India to create a separate Sikh state, known as Khalistan. The idea now only exists within the romanticism of a minority of the Sikh diaspora, and as a tool Pakistani intelligence uses to annoy New Delhi. The Indian government gives outsize weight to these factors.

Working against – or in unison – with this are Canada’s democratic realities. Around 1.5% of the Canadian population is Sikh, but as a publicly engaged and well-organised group, they play a major role in Canada’s domestic politics. There are currently 18 Sikh politicians in the House of Commons, 13 more than in India’s lower house. A number of vital electorates in Toronto and Vancouver simply cannot be won without the support of the Sikh community.

This often leads Canadian politicians to make attempts to engage with the Sikh Canadians, only to aggravate New Delhi. Trudeau himself has been a master of this, whether it has been attending a Khalsa Day parade in Toronto in 2017 where Khalistani flags were waved and images of Sikh militants were put on display, or inviting a man convicted of terrorist charges to receptions in Mumbai and New Delhi on his disastrous trip to India in 2018.

For its part, the Indian government tends to conflate Sikh-specific issues – like those seeking justice for victims of the 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom – with agitation for a separate Sikh state. At present, Modi’s government is trying to paint protesting farmers – the majority being Sikh – as Khalistani separatists or other “anti-nationals”, a favoured term for anyone critical of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

With the protests being watched closely by the Canadian Sikh diaspora, in December Trudeau both infuriated and perplexed New Delhi when he issued a statement in support of the protesting farmers – even though the new agricultural laws would benefit Canadian farmers exporting to India.

Which leads back to last week’s phone call. Due to Canada’s unique pandemic needs and India’s outsize vaccine manufacturing capabilities, a new power balance has emerged between the two countries, one that has the potential to attach itself to these pre-existing issues. This raises two questions about how this form of vaccine nationalism may work: Will the power of access to the vaccine outweigh Canada’s democratic realities? And will the leverage New Delhi now holds be used to make a point to Ottawa that it needs to tread lightly around India’s sensitivities?