Chaos is a ladder, said Littlefinger in Game of Thrones. Crisis is an opportunity, Sun Tzu didn’t say in The Art of War. Either way, in the United States, as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and “infodemic”, political chaos is a clear and present danger, and an opportunity, in the covert and overt information wars between America and China.

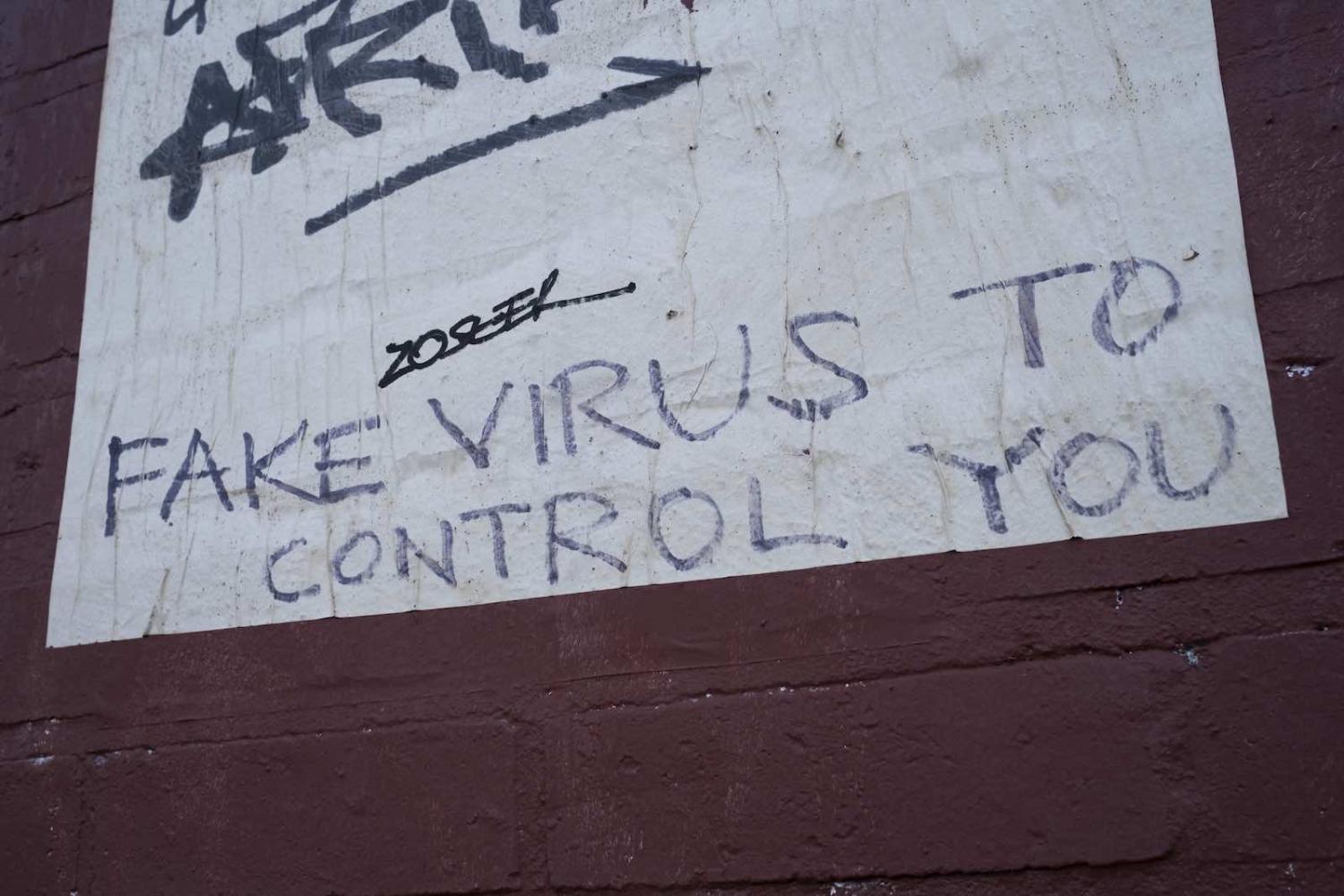

Media reports citing US intelligence sources and think tanks suggest that China has identified the schisms in American politics as openings they can and should exploit. Disinformation campaigns involving Chinese operatives amplified phony news stories, such as an apparently imminent threat that the US government was sending troops onto the streets to support a national shutdown.

The how and why of this is important: they offer lessons in the vulnerabilities of any society to these sorts of online disinformation campaigns, as well as revealing the motivations of who might be running them.

For Australia, the grim lesson is that the online communications environment shares many of same characteristics that make the US vulnerable. There is little prospect of that changing.

Awaiting further proof, it is important to consider these campaigns may be state-directed, or could be the products of a more loosely coordinated network of Chinese online actors, such as identified by ASPI’s Cyber Policy Centre, or something else. But enough is known about the nature of these campaigns to characterise how they work and why they are attempted.

Motivations first. Why might China engage in these types of information wars? For one, it fits with the model of the “three warfares”, which includes public opinion alongside legal and psychological warfare. Information wars were not invented recently, but China has learned the lesson from Russia’s efforts in 2016 in the US and elsewhere and seen how they work.

Information wars serve two purposes for the Chinese military, who, we must remember, firstly serve the Chinese Communist Party, rather than the Chinese nation.

The first purpose is to buttress the CCP from internal pressure. There are significant and legitimate questions being asked about the response of Chinese authorities to the coronavirus outbreak, hence the need to turn up the volume on the standard narratives that both undermine Western (specifically American) systems of politics and present the outside world as antagonistic to China’s rise, sometimes referred to as Chinese “negative soft power”. This is not new.

The second purpose is to support efforts to diminish US influence internationally and thereby reduce American capacity to curtail China’s activities on the global stage. This is accompanied by a more confrontational approach by Chinese diplomats on social media and signals a greater confidence in its position and, perhaps, its national brand.

That is the why. What about the how? Fortunately for disinformation warriors, much of the hard work has been done for them.

Disinformation campaigns work best where several criteria are met.

The first is a large, connected online community of interest, which provides a network effect, spreading disinformation far and fast. As in epidemics, so in viral media. Super spreaders can greatly enhance the virality of a message, so those with significant influence (through network position or cultural and political importance) can exacerbate matters.

The second is a population sufficiently distrustful of authority, especially politicians and mainstream media. American political discourse meets both criteria easily: President Trump and his cheerleaders act as super spreaders and promote distrust in political and media elites (while being elites themselves).

The third relates to what is known as “crisis infomatics”: situations of high anxiety and low certainty which are conducive to the spread of both disinformation (deliberative, by malicious actors) and misinformation (uncoordinated, by well-meaning actors unwittingly spreading false hope). The Covid-19 pandemic is distinct in that uncertainty has been high for much longer than typical of other emergencies, such as a terrorist attack, mass shooting, or large-scale disaster.

Lastly, disinformation content is more spreadable if it is more emotive. Righteous anger is effective. It also helps if it has some level of homespun “truthiness”, as opposed to institutional authority. American nativist populism feeds on anger and rates folksy axioms over science. Such circumstances lead to soaring reproductive rates for viral conspiracy theories.

These factors are well known and have been exploited by foreign actors seeking to disrupt American politics and society since at least 2016. All combined, they demonstrate that the online media environment in the US is ripe for disinformation campaigns and is a product of local conditions, not a creation of foreign actors.

Worse, the limited efforts by tech giants against coordinated inauthentic campaigns are increasingly ineffective, as malicious actors can either amplify community-based campaigns on social media, or they can use encrypted messaging and SMS services. Neither of these are easily tracked.

All this remains the case despite the recent efforts to limit the spread of misleading Covid-19 information. The tech giants remain deeply opposed to similar checks on online political falsehoods.

For Australia, the grim lesson is that the online communications environment shares many of same characteristics that make the US vulnerable. There is little prospect of that changing.

But a happier conclusion arises out of the relatively sensible and sober discussions that have so far characterised Australia’s response to Covid-19. By quarantining misleading rumours to the outer fringes of political discourse, and presenting policy led by medical and scientific expertise, there is less occasion for malicious actors to turn chaos into opportunity.

This hard lesson should be remembered and applied beyond the times of Covid-19.