Australia’s space activities have always been driven by a mix of defence and civilian interests. But what is needed now is a single strategy to guide the various arms of government in the new frontier.

Historically, Australian governments were content with leaving space to individual departments and institutions, seeing it as an arena through which to achieve objectives in other policy areas, not least security. Maintaining relationships was a key part of space activities: Australia’s most famous space contributions – at Woomera, hosting tracking stations in support of the moon landings, and launching its own satellite – were all conducted with other nations.

The still-strong relationship with the United States in space reflects Australia’s approach in space. Here Australia’s geographic position in the Southern Hemisphere, and its strategic, political and cultural alignment with the west made it an attractive place to host tracking and data relay stations. For its part, Australia has always supported American space efforts as a way by which to cement the relationship. While Pine Gap is the clearest example of this, the agreements to support the moon landings and subsequent NASA spaceflights were also entered into because space represented a medium in which Australia had something to offer an ally with which it desired a closer relationship.

Space is vital to Australia’s relationship with the United States, while the United States is in turn central to Australian activities in space, whether via Pine Gap, the prospect for increased cooperation in space under the recently announced AUKUS military arrangements, burden sharing in communications satellites, and scientific and industry cooperation.

At the same time, the question of how much Australia should seek its own sovereign capability in space is increasingly being asked by Defence and industry professionals.

On the civilian side of the ledger, the creation of the Australian Space Agency (ASA) in 2018 came at the end of a decade of slow but steady realisation that space was not just a useful part of Australia’s economy but a vital one. Incidentally, when the United States Congress formally congratulated Australia for the creation of the ASA, it did so by first referencing the two countries’ long military cooperation.

Despite the creation of the ASA, Australia’s approach to space remains disjointed. While having achieved a broader discussion of space through the public-facing ASA and through the construction of space structures in Defence such as the new Space Division, neither the civil nor defence space sectors have comprehensive space policies.

Although a Defence space policy has been mooted for over a decade, it is still in development. While there is a civilian space policy, Advancing Space: Australia’s Civil Space Strategy, 2019–2028, this reflects current government interest in the economy, and is overwhelmingly focused on jobs and economic growth. While an important part of the discussion, it is but one element of Australian space. Science, research, international cooperation and overlap with Defence are all mentioned in the opening sentences, but no further.

In scientific, engineering and social science space research, focused goals in space would help to harness Australia’s scholarly expertise.

Most crucially, why Australia wants a strong space sector is not discussed beyond the possibility of economic benefits.

Compare Australia’s approach to that of the United States. Written under the Trump presidency but accepted by the Biden administration (one of the few such policies), the US National Space Policy recognises that American space activities encompass “three distinct but interdependent sectors: commercial, civil, and national security”, laying down explicitly cross-sector policies alongside sector-specific guidelines. Put simply, the American space policy recognises that a variety of sectors have interest in space, but also that clear government direction is necessary for those areas that overlap. Australia does not.

Bringing together the various arms of government with a single policy offers a launching pad for Australia’s space future. In scientific, engineering and social science space research, focused goals in space would help to harness Australia’s scholarly expertise. At the same time, such a policy would allow for sustainable growth within industry, linking what the Space Industry Association of Australia has called “disjointed space priorities, policy and funding”.

Within the alliance, a clear and focused space policy would allow for the harnessing of local capability to enhance the relationship with the United States, should that be a desirable future. Initiatives such as the development or purchase of satellites, a modest launch capability, or other space or ground-based capabilities represent an opportunity to burden share with alliance partners or to lead the region.

Given the contested and congested nature of space today, the absence of a comprehensive space policy risks continuing Australia’s historically fragmented approach into a new era of space. Equally, there are significant benefits to developing such a policy, including a single national voice on a vital domain of national endeavour, a sustainable space industry and burden-sharing opportunities within the alliance.

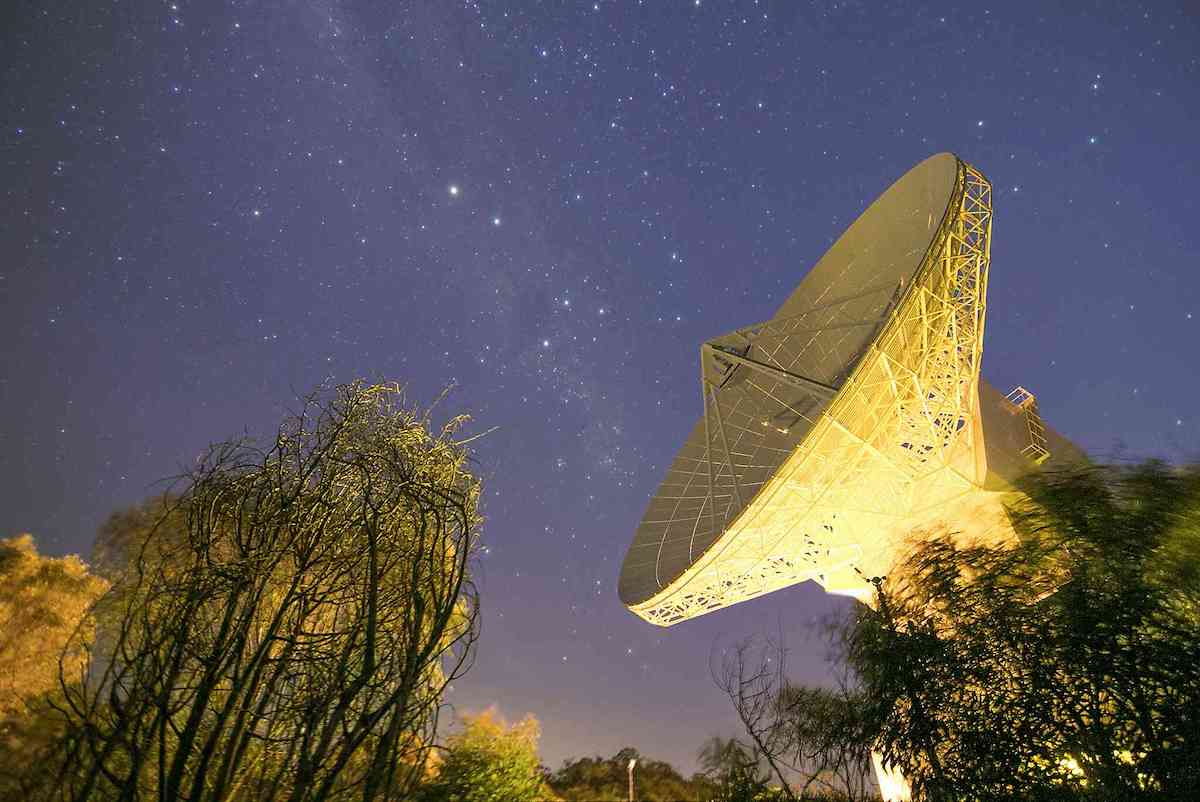

Main photo via Flickr user Trevor Dobson