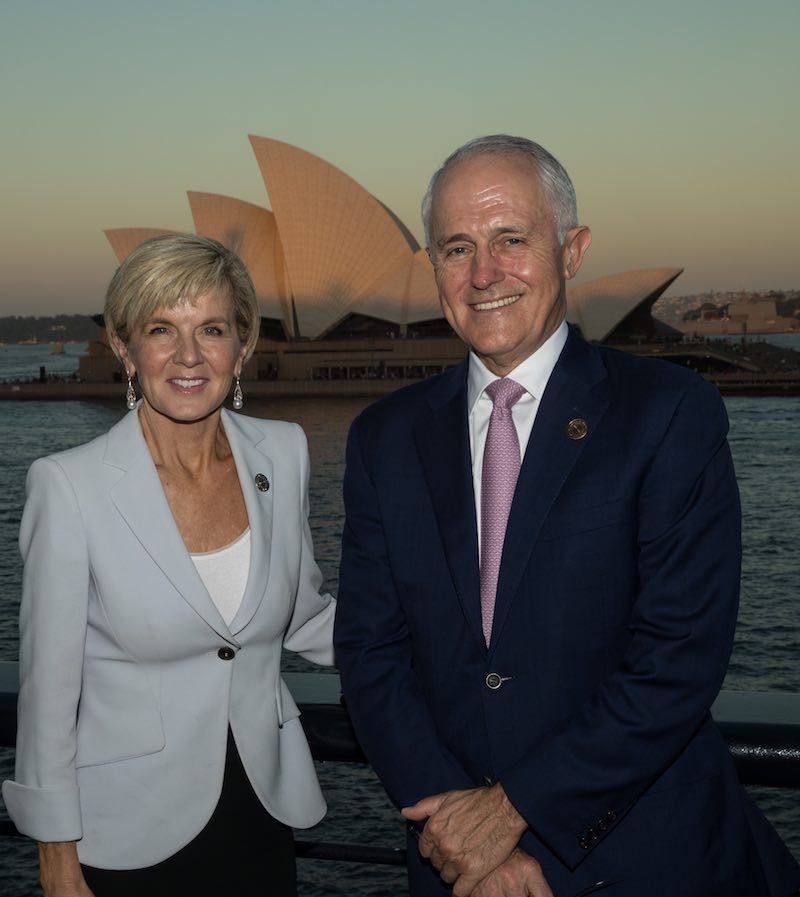

Julie Bishop resigned as Foreign Minister on Sunday, just short of her 20th anniversary as member for Curtin in Western Australia, and her fifth as Foreign Minister. In the coming days, there will no doubt be numerous reflections and dissections of her time as Foreign Minister. Deposed Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull hailed her as Australia’s finest foreign minister. Other international relations experts might offer praise, if somewhat more muted.

I offer a more personal evaluation, based on my own experience of Bishop as a Foreign Minister who made a formidable impression wherever she went, whether local, national or international. From my observations, she is smart, charming, quick and thorough across a brief, immensely hard-working and conscientious. She has carefully developed relationships with leaders across the globe, and her Twitter diplomacy is world class. She makes a mean speech and does it without notes or props (except, on occasion and to great effect, her hair, or steely glare).

For some, Bishop may not have laid out a grand strategy for Australia’s role in the fast-changing geopolitics of the 21st century, but then again, that’s no easy task in these strange times. For me, her achievements lie in the goals she chose to pursue, and which she then pursued with determination and rigour.

She wasted no time after her appointment, launching the “New Colombo Plan” as her first and probably her signature initiative in December 2013. The idea was to promote Asia literacy in Australia by supporting scholarships for Australian students to study and intern in the region. Not wildly original, but effective: from a modest pilot in four countries in 2014, it has grown to fund around 10,000 scholarships for Australian undergrads each year.

The first Abbott-Hockey budget in 2014 was a bad one for Bishop. The axe swung on the aid budget, cutting it by more than $7 billion over the forward estimates. What she managed to achieve, however, was a quarantining of Papua New Guinea and the Pacific from those cuts. Since 2014, Australian aid has dropped by a quarter in real terms, to the lowest proportion of gross national income in our history. At times, Bishop’s frustration with her own government’s approach to aid was evident. However difficult a task, she has managed to maintain aid to the Pacific in real terms, right up to the latest budget.

The second Abbott-Hockey budget in 2015 was a better one for Bishop, and it represented a turning point for the meagre means with which Australia prosecutes its foreign affairs. After years of stagnating budgets for diplomacy and the closure of diplomatic posts, the 2015 budget announced five new posts in priority locations, after years of dithering on the issue during the Rudd and Gillard years. Since then, five further posts have been opened, giving truth to one of Bishop’s favourite claims that this is “the single largest expansion of Australia’s diplomatic network in over 40 years”. While the words of a couple of Lowy Institute papers “ringing in her ears” might have encouraged Bishop to pursue this particular course, that does nothing to lessen the importance of this achievement – although it was a nice moment for me, personally.

In consular affairs, Bishop really dug her heels in. The fact that she failed to save the lives of the two Australians on death row in Indonesia over drug smuggling in Bali says less about her own vigorous diplomacy with Jakarta than it does about Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s determination to enforce a tough line on drugs, let alone the well-documented mis-steps of Bishop's then boss. This combined with a nasty poll result saying that Australians supported the death penalty in such a case, despite later polling from the Lowy Institute which did not validate that macabre view.

That case demonstrated Bishop’s approach to the consular mission of the Australian government: focus on the crucial role of defending Australian lives, as she did following the MH17 disaster, and not on gaining favourable publicity for the government in cases of Australians behaving badly overseas. She presided over the first formal consular strategy for the government, which emphasised the importance of “promoting a culture of responsible travelling”. With more Australians travelling overseas than ever, and consular cases becoming increasingly complex (such as forced marriages, child abductions, custody disputes and mental illness), this was a crucial intervention at the right time.

As Minister, Bishop studiously avoided publicising her interventions in the daily fare of extricating Australians from tricky situations abroad, while supporting her department’s work behind the scenes.

These are just three examples of Bishop articulating a goal and then acting. Whether she is Australia’s “finest foreign minister” is a judgement others can make (and already are). Some have observed that she has been underestimated. Her performance at the United Nations in the aftermath of the MH17 downing has been held up as an example of first-rate diplomacy. She took firm stances on China’s unilateral declaration of an air defence identification zone in the East China Sea in 2013, and again in 2017 on China’s failure to abide by the legal result in the South China Sea arbitration. She has refused to be bullied. She has made a forceful case for the preservation of the rules-based order which has benefited Australia, the West, and developing nations. She has earned friends in the region and beyond.

One thing is certain: she is Australia’s finest female foreign minister, because she is the first. That is no small achievement, at a time when achieving a senior role in diplomacy or national security is a rare feat for a woman.

And how exactly should the performance of a foreign minister be judged, anyway? Should it be by the number of treaties concluded and the grand bargains achieved, or the steady and warm relationships forged both in the near region and further abroad, discipline in the consular function restored, the profile of the ministry lifted and popularised, the hard work of rebuilding a depleted network begun in earnest? Some of these achievements may not make the history books, but Bishop’s place there is assured regardless.