In 2014, the average Indian voter was restless for change. Regular revelations about corruption scandals, frustrating policy paralysis, incessant price hikes and widespread unemployment all coalesced in a virtually stalled economy. In polls that year, the Indian electorate delivered the Bharatiya Janata Party to government with an absolute majority and a mandate to follow through on its policies without restraint, a result not seen in Indian politics for some three decades.

It was as if the Indian electorate voted for a messiah, hoping that in one stroke Narendra Modi would change India’s destiny. And indeed, Modi’s name was made synonymous with reforms and development. He spoke passionately about the need for speed in government decision-making, for bureaucrats to be enablers rather than regulators, reinforced by minimum government and maximum governance.

He came to the top job at a time when macroeconomic indicators were at their worst, the fiscal deficit was high, and with India facing the worst economic slowdown since the 1980s as investment growth hit an 11-year low. A report by credit rating agency Moody’s cautioned that India would not be able to revert to high growth path of 7–8% even if it pursues a strong reforms agenda. Other economists offered similarly dire warnings after the growth rate almost halved in just two years:

India’s current economic woes render it critically ill and in need of intensive care.

All this can be characterised as a kind of “ICU” view of the economy – one where a turnaround would rest on setting the right incentives, with credibility and urgency to drive both policy and implementation.

So, five years on, with another election about to be held, a judgement of Modi’s promises is about to be made. And in one area in particular, that of encouraging foreign direct investment, his record is strong. India has received foreign direct investment worth US $239 billion in the last five years.

Modi’s long experience as chief minister (unusual for an Indian Prime Minister) gave him a different lens. He acknowledged early in his economic agenda that the transformation of India would require a transformation in each of its 29 states. It is state governments that ultimately deliver most public services important for the success of any domestic or foreign business enterprise – whether education, health, roads and power.

Modi’s long experience as chief minister – unusual for an Indian Prime Minister – gave him a different lens.

Under Modi, the states have been encouraged to compete for foreign direct investment. While 15 states have come up with an export policy or strategy, 21 states have also appointed export commissioners. Chief Ministers have also been spruiking for investment from overseas, the past few years seeing these state leaders travel to Singapore, China and Japan, while state specific investor summits have become common, such as in Gujarat and Uttarakhand. The aim of the states has been to create investor-friendly policies, monitor investment applications and follow up with the interested companies. In that context, Gujarat has one of India’s highest implementation to proposed investment ratio. Politics and priorities also explain the state-level divergence in attracting FDI. Not all states have the same flourishing record.

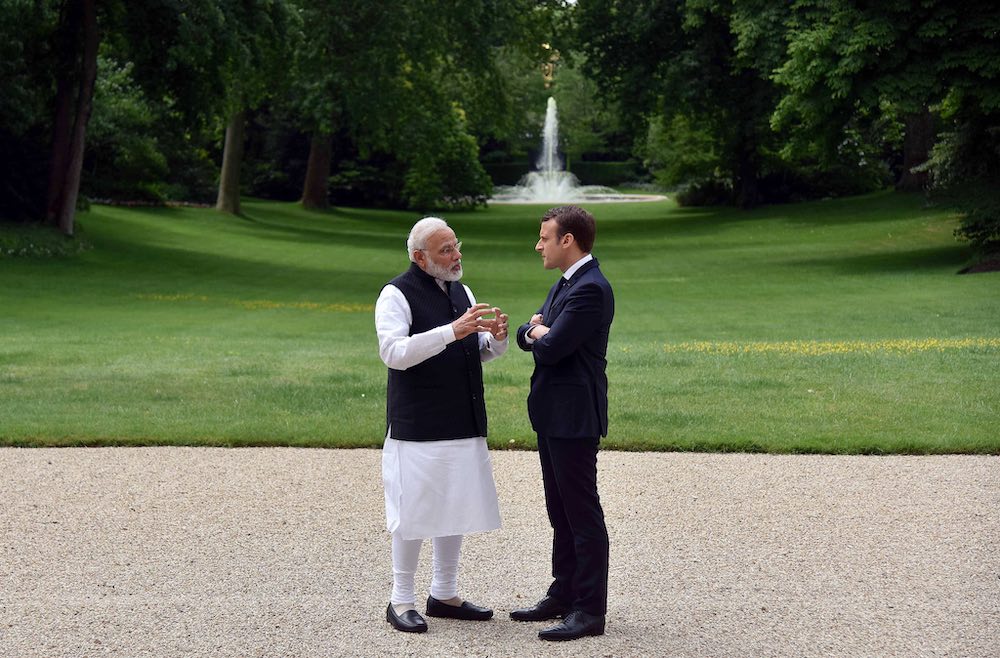

Modi has also made attracting investments his personal mission. A big part of his overseas tours has been a deliberate effort to integrate foreign policy with economic and corporate policies. He meets with CEOs of global business giants to attract foreign direct investment, as well as seeking to engage the 20 million-strong Indian diaspora around the world.

His pitch was clever, as he said early on in his term, “FDI should be understood as ‘First Develop India’ along with ‘Foreign Direct Investment’”. The aim was two-fold, not only to attract foreign investors but also spur domestic players into investing in industry, with his promise to lay out the “red carpet” instead of “red tape” to boost investor confidence. The eventual passage of the Goods and Services Tax also helped, coming after 17 years of debate and delay, along with reforms to the insolvency and bankruptcy code.

The success of this drive to liberalise India’s foreign direct investment regime is clear from the results, particularly in crucial sectors such as defence, e-commerce, civil aviation, construction and development, real estate and pharmaceuticals. The last four years has seen a record average inflow of $52.2 billion in FDI annually.

Among the countries that Modi visited, Japan committed to invest about $35 billion and South Korea about $10 billion. China assured $20 billion, France announced $2.26 billion, and the UAE pledged to contribute to India’s $75-billion infrastructure fund.

The whole exercise is aimed at providing investor friendly climate to foreign players and in turn attract more FDI to boost economic growth and create jobs. Foreign investments are considered crucial for India, which needs around US$ 1 trillion to overhaul its infrastructure such as ports, airports and highways. FDI also helps improve the country's balance of payments situation and strengthen the rupee against other global currencies, especially the US dollar.

Confidence is up. In a marked turn-around from 2013 when Morgan Stanley labelled the country one of the “Fragile Five” emerging market economies, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development now calls India one of the most favoured investment destinations globally.

But substantial progress cannot be the end in liberalising foreign investment policy settings. If India is to attract the capital required to boost productivity, create employment opportunities, and deliver real improvements to living standards, more needs to be done to offer greater certainty to investors.

Chief among the government’s unfulfilled reforms are those related to labour and land acquisition. The world’s fastest-growing large economy can no longer run on 20th century laws. It needs a different legal architecture to face future challenges. Stringent and complex regulatory laws have kept investors out of the manufacturing sector, which can drive jobs growth. Services continues to draw more than 60% of total FDI inflows, and a large part of FDI is in the form of acquisitions, which doesn’t lead to more jobs.

Status quo on land, labour laws won’t help. India needs to think big and deliver innovative policy solutions. The judgement on Modi’s record should ultimately rest on creating jobs.