I suppose Will Hodgman has plenty of experience in charge of a small island state. Because otherwise it’s a bit of a puzzle why the former Liberal premier of Tasmania should be picked as Australia’s next High Commissioner in Singapore, as was announced this week.

Labor was quick to brand Hodgman’s appointment another case of “jobs for mates”, which is standard political sparring whenever a retired politician of either persuasion is handed a diplomatic posting. Foreign Minister Marise Payne defended the decision, saying Hodgman will bring extensive experience in “trade and tourism” and “putting Australia first in everything that he does”.

But beyond the politicking, the choice does underscore a notable shift in Australia’s diplomatic network, one that only becomes clear when tallied alongside other recent political appointments.

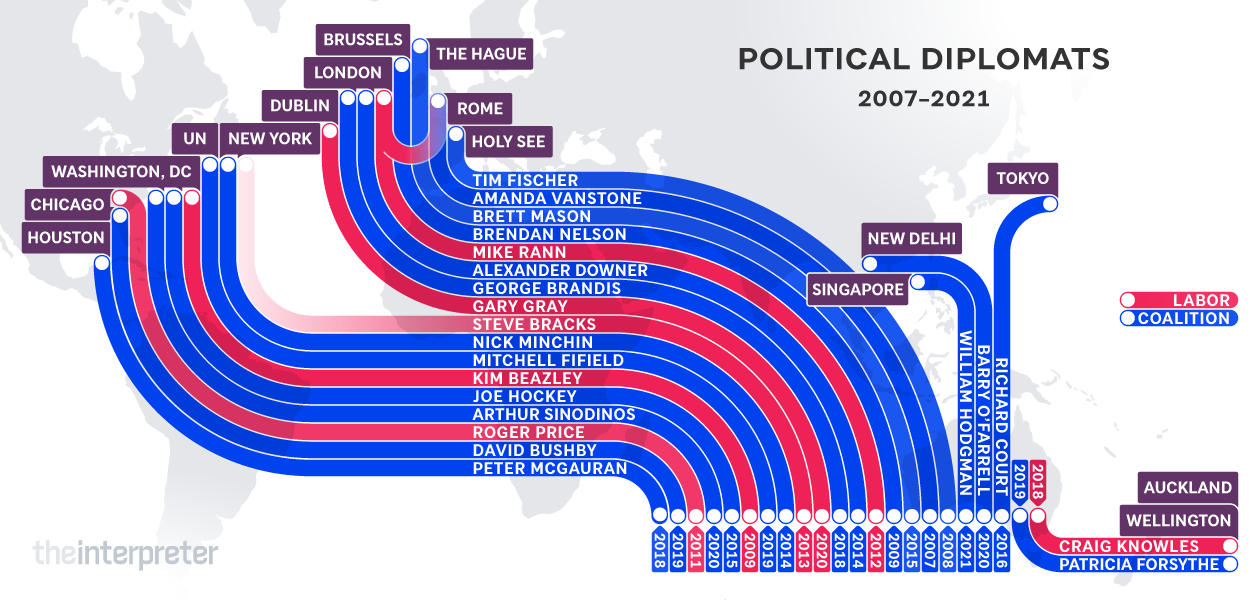

Not only has there been a rise in the number of politicians-turned-envoys, they are being sent to more posts that were once the exclusive domain of career diplomats. This map illustrates.

Dispatching Hodgman to Singapore marks the first time an ex-politician has served in this role. Former NSW Liberal Premier Barry O’Farrell similarly notched up a first in May when he presented his credentials as Australia’s High Commissioner to India.

In 2016, former Western Australian Liberal Premier Richard Court became only the second ex-politician to serve as Australia’s ambassador to Tokyo in the post-war era, the last having been sent in 1970.

While last year, former Victorian Liberal senator Mitch Fifield also became the second ex-politician to be made Australia’s permanent representative to the United Nations in New York, following South Australian Liberal Robert Hill who held the job from 2006. (Labor’s Norman Makin lead Australia’s delegation at the formation of the UN in 1945.)

Wellington had been a more regular haunt for ex-politicians to represent Australia until the 1980s, but the appointment of former NSW Liberal MP Patricia Forsyth last year as High Commissioner to New Zealand broke a long-running streak of senior career diplomats in the role (former Defence minister David Johnson had rejected the Wellington job in 2015). Former Queensland senator Brett Mason was the first former politician in 20 years to become Australia’s ambassador to the Netherlands when he was appointed in 2014.

This shift raises fascinating questions. Does it reflect the changing contours of power in the world, and with it a fresh judgement about the key capitals most important to Australian interest? Or is a creeping suspicion taking hold within the political class about the foreign service – something akin to US President Donald Trump’s railing against the “swamp” in Washington? Independent senator from Tasmania Jacqui Lambie appeared to be alluding to this issue while quizzing Payne in parliament by listing the career credentials of Hodgman’s recent predecessors in the Singapore role and asking why he was better qualified.

If this increased spread of political appointments becomes the norm, at some stage we’ll see an envoy abroad wind up on the wrong side of a change of government back home.

It used to be that ex-politicians went almost exclusively to London or Washington, the justification being that a senior voice was required to ensure Australia’s opinions were heard. Hence Kevin Rudd sent former Labor leader Kim Beazley to Washington in 2009, Malcolm Turnbull replaced him with former treasurer Joe Hockey in 2015, and in turn Scott Morrison this year appointed former NSW senator Arthur Sinodinos.

Or it might be that an ex-politician would be rewarded (some with long memories of former Democratic Labor Party Vincent Gair in the 1970s might say “retired”) with a gig at a relative backwater for Australia, such as Dublin or the Holy See, or perhaps a consul general gig somewhere in the United States. Former Victorian Labor premier Steve Bracks was packing his bags to be Australia’s representative in New York in 2013 only to be sacked just prior to departure following a change of government. Ex-Liberal senator from South Australia Nick Minchin subsequently filled the job.

It was a rare case that a politician would volunteer for a hardship posting, such as former Labor senator Kerry Sibraa serving as Australian High Commissioner to Zimbabwe in the 1990s.

Beyond one-time politicians, the count is also complicated when “non-career” appointments are added, those drawn from outside the diplomatic service but still made by executive fiat. The OECD Paris representative job has oftentimes been filled by a former ministerial adviser, including the incumbent, Alexander Robson. Tony Abbott also sent former Australian Federal Police chief Tony Negus to Ottawa in 2014, as well as former adviser Mark Higgie to Brussels (Higgie had also previously worked for the Foreign Affairs department). Bob Carr sent Sydney barrister John McCarthy to the Vatican and Paul Keating made former adviser Don Russell ambassador to Washington. Years before, Gough Whitlam sent journalist and author Bruce Grant to India and adviser Stephen FitzGerald to China (FitzGerald had earlier worked for the then Department of External Affairs).

More recently, occasional outbreaks of bipartisanship have seen political spears set aside. In June, Payne dispatched former federal parliamentarian and ALP national secretary Gary Gray to Dublin, and in 2018 the Coalition government made NSW Labor MP Craig Knowles consul-general in Auckland. In Rudd’s first stint as prime minister he sent the Liberals’ Brendan Nelson to Brussels and the Nationals’ Tim Fischer to the Holy See.

But if this increased spread of political appointments becomes the norm, at some stage we’ll see an envoy abroad wind up on the wrong side of a change of government back home. Former South Australian premier Mike Rann, appointed to London by Labor in 2012, was pulled out by the Coalition in 2014 to allow Howard-era foreign minister Alexander Downer to take up residence in Australia House. Rann’s consolation prize was to be sent to Rome. A more elegant solution in future might be for Australia to adopt the US tradition of political diplomats offering to resign when a government changes.

At the very least the government should better explain why so many politicians suddenly discover the qualities that make excellent envoys. And who knows – maybe we’ll see one posted to Jakarta or Beijing soon?