Book review: Politics on the Edge: A Memoir from Within, by Rory Stewart (Jonathan Cape, 2023)

To explain away their failures, errors and flaws, many politicians have consoled themselves with the words of Ecclesiastes. “The race is not to the swift … nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill, but time and chance happen to them all.”

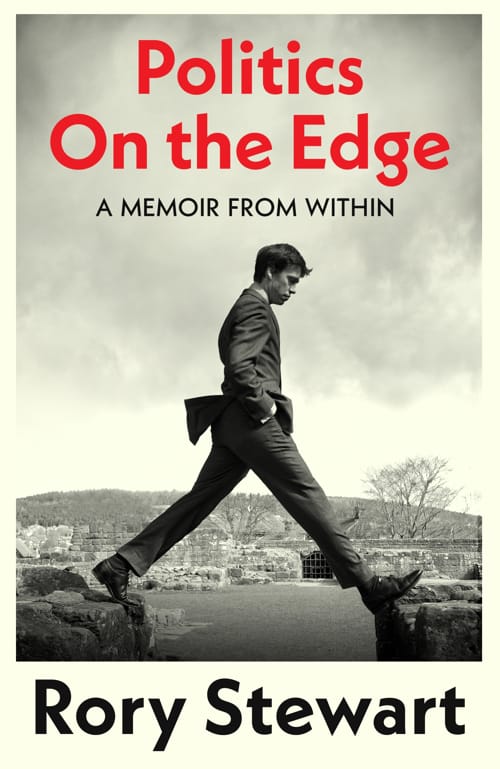

Few men or women, even those few of understanding and skill, have crafted a memoir at once so elegant and so excoriating as Rory Stewart’s Politics on the Edge. Stewart resigned as a British cabinet minister in 2019 on an issue of principle, unavoidably abandoning a constituency that he cherished, a cause to which he had committed himself, and a career in which he had been conspicuously successful.

Time and chance intervened, but so too did Brexit and Boris Johnson. Happily, Stewart could fall back on the capacity for intense observation, wry judgment and self-awareness, first honed in an account of a walk across Afghanistan (The Places in Between).

Stewart’s most pungent criticism of his fellow politicians (among many such) is included amid a description of a leadership debate. “Our brains have become like the phones in our pockets: flashing, titillating, obsequious, insinuating machines, allergic to depth and seriousness …”

For his part, Stewart seems to have built a career in politics (his fourth or fifth) on the old-fashioned but durable virtues of “depth and seriousness”. This book tracks the novice minister as he attempts to do some good with floods, forests, Africa, prisons, the probation system, climate change and development spending.

Stewart is unsparing about his own lack of relevant experience, with the major exception of Britain’s development assistance. Having run aid programs in Iraq and Afghanistan, Stewart could bring an especially informed, inquiring approach to occasional pretensions and illusions from the then Department for International Development.

Senior politicians and officials have long complained that each laughs at the wrong point in Yes, Minister. Having administered provinces and programs, Stewart was well placed to laugh at both sides – while chiding, encouraging and shaming them both.

Although Johnson, “a chaotic and tricky confidence artist”, remains Stewart’s main target, Liz Truss’ “allergy to caution and detail” is roundly deplored, as is David Cameron’s “half-sentences and truncated imperatives, as though he were dictating in the bath”. (Welcome back as Foreign Secretary, Lord Cameron.)

As for public servants, those who resisted any ministerial attempt to wrest control of “the routines of the ship of state, its trim and its daily navigation”, Stewart is sometimes sharply critical, respectful and trusting of others. He does appear to agree with his ministerial colleague, Michael Gove, who he cites as suggesting that the Westminster system leads public servants to treat ministers like “child emperors, to be indulged, praised and manipulated”.

What then to make of policies that, Stewart declares, may reveal “the squalid ineptitude of British government”? Might a once great country be stigmatised, as Stewart does British prisons, on the basis that “the whole system had lost its belief in itself”? Behind and beneath many of the problems with which Stewart wrestled might lie Cameron’s misguided austerity, but Stewart also senses something morally wrong.