At last month’s annual Valdai forum in Russia, President Vladimir Putin said it was “impossible” to deny climate change when disasters had become “almost a norm”.

Acknowledging the reality and hazards of climate change is a big change for Russia’s leader.

But how meaningful is this apparent shift?

Climate change undoubtedly poses risks for Russia, as the upsurge in wildfires and melting permafrost across Siberia in recent years has shown, affecting lives, livelihoods and infrastructure.

Yet Moscow’s interest in climate change has hitherto been desultory. The Kremlin has tended to downplay it – and, if anything, highlight the potential pluses a warming climate might offer Russia. Nor has climate change been a major domestic issue publicly.

Global efforts to reduce emissions and diversify energy supplies away from fossil fuels represent a serious, long-term threat to Russian energy exports, and wider Russian economy.

Russia is the world’s fourth largest emitter of greenhouse gases, pumping out five per cent of the world’s carbon. It is also a significant source of methane emissions, often from creaky gas pipelines. Yet Russia only ratified the Paris Agreement in September 2019, four years after its conclusion. And its Nationally Determined Contribution lodged in November 2020 was a modest effort, rather devoid of ambition. It committed only to reduce carbon emissions by 2030 to 70 per cent of 1990 levels – a soft target, given substantial post-Soviet era de-industrialisation.

Indeed, the government’s Energy Strategy 2035 adopted last year envisaged continued expansion of fossil fuel production, while renewable energy and energy efficiency ambitions don’t go far enough. Unsurprisingly, then, Russia’s climate targets, policies and finance have been deemed “critically insufficient”.

But over the past year, the Kremlin has started taking climate change seriously – at least, rhetorically.

In his annual state-of-nation speech in April, Putin declared that Russia’s total net greenhouse gas emissions should be less than the EU’s over the next 30 years, describing this as a “tough” but “realistic” goal.

A draft climate strategy currently under discussion among Russian government agencies (but yet to be formally adopted) describes plans to cut carbon emissions by 79 per cent by 2050. To meet this target, though, considerable (yet debatable) store is set on the capacity of Russia’s vast reserves of forest and swamplands to act as natural carbon sinks to absorb emissions.

And addressing an energy conference in Moscow in early October, Putin committed Russia to achieving zero net carbon emissions by 2060.

In part, Russia’s shift on climate change mitigation is in response to external economic pressures. Global efforts to reduce emissions and diversify energy supplies away from fossil fuels represent a serious, long-term threat to Russian energy exports, and wider Russian economy. In particular, the European Union’s plan to levy a carbon border tax on imports from states that aren’t doing enough to reduce greenhouse gas emissions jeopardises Russian exports; Europe takes 45 per cent of Russian exports, mainly oil, gas, coal, metals and fertilizer, so this could hit Russia badly.

Russia, then, has some incentive to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy – or at least be seen to be trying.

Yet this will be difficult.

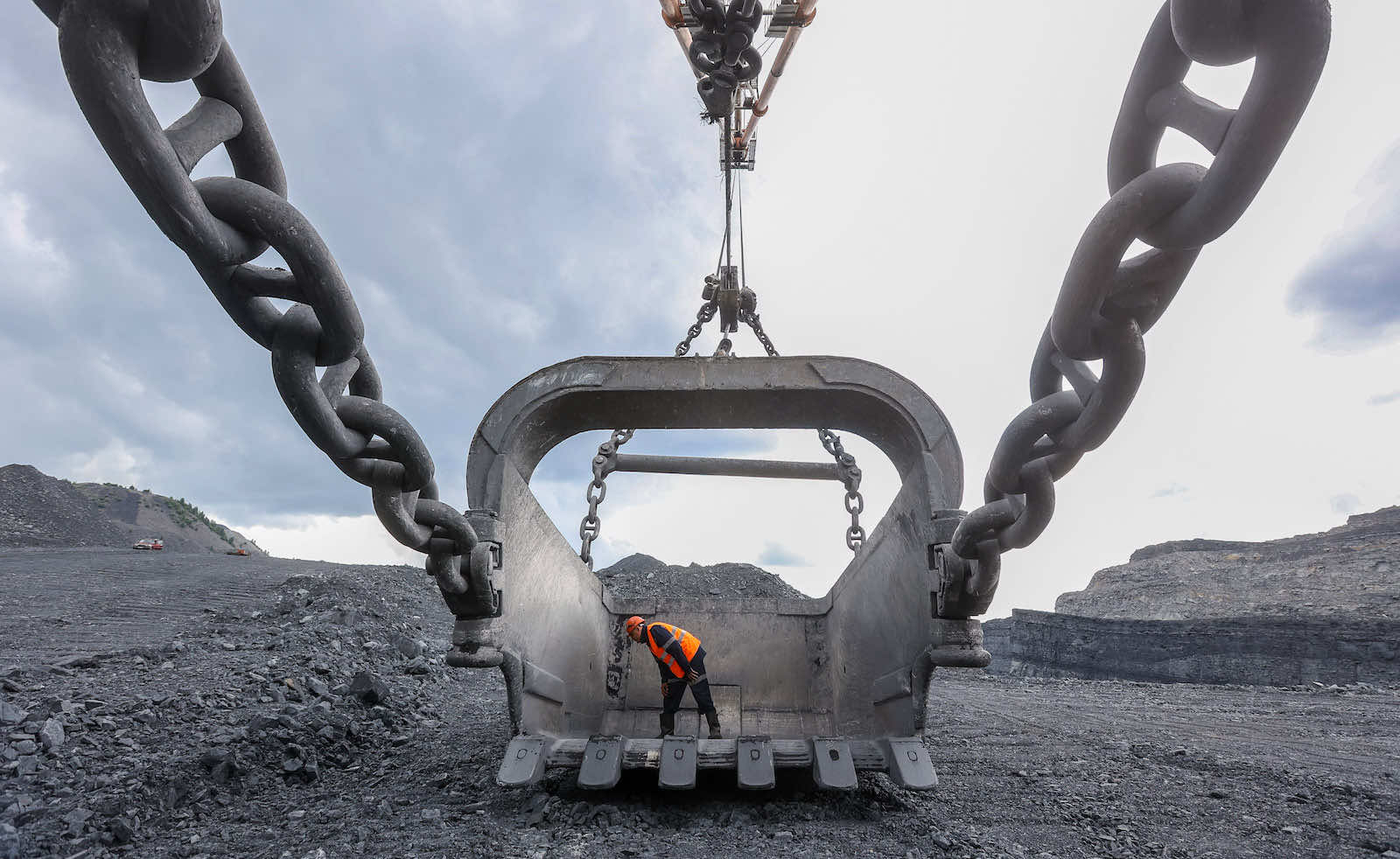

Hydrocarbons – oil, gas and coal – play an outsize role in the Russian economy. Nearly 90 per cent of Russia’s energy comes from carbon-heavy sources, while oil and gas provide over 35 per cent of government revenues. And there is a social dimension: big parts of the country are dependent on oil, gas and coal extraction to provide revenue and jobs.

Russia continues to see opportunities in a warming climate – both economic and geopolitical.

Moreover, Russia’s authoritarian political system relies heavily on the Kremlin’s control over state-run energy giants – and their revenues. And internationally, Russia leverages its leading role in global energy flows to increase its geopolitical influence, as we’re seeing now in Europe’s gas supply crisis.

All this gives some reason to be sceptical of Russian intentions and the credibility of its latest climate pledges. The vital importance of fossil fuels for Russia – politically, economically and geopolitically – arguably gives Moscow an interest in dragging the chain on global climate change mitigation efforts.

Russia continues to see opportunities in a warming climate – both economic and geopolitical. This includes expanding agricultural production in Siberia and the Far East, opening up greater access to energy and mineral resources in Arctic regions of northern Russia, and facilitating expansion of shipping along the Northern Sea Route between Asia and Europe. China figures prominently in Russia’s thinking in all three areas.

Russia’s energy strategy also bets that the world’s transition to a less carbon intensive future will be slow, and that fossil fuels will be needed for longer, especially in countries like China and India.

Yet ironically, Russia has huge potential to expand renewable energy production – solar, wind, geothermal, biofuels, hydrogen – especially given its size, strong scientific base, and sheer variety of climate zones. Using hydrocarbon revenues to build green energy infrastructure would be a smart move by Russia to prepare for energy transition.

Chances are, though, that strong vested interests – political and economic – will resist and slow Russia’s energy transition, ensuring that fossil fuels remain dominant in the country’s energy mix for the foreseeable future, whatever rhetorical stance Moscow adopts at the upcoming COP 26 meeting.