Earlier this month, the Lowy Institute released Being Chinese in Australia, one of the largest surveys of the Chinese Australian community. Around the same time, the Scanlon Foundation published its annual Mapping Social Cohesion report, which also includes a survey on the Chinese population in Australia. Both surveys find significant shares of Chinese Australians reported having been threatened or attacked in past year, and many respondents associated their negative experiences with the debate surrounding Covid-19.

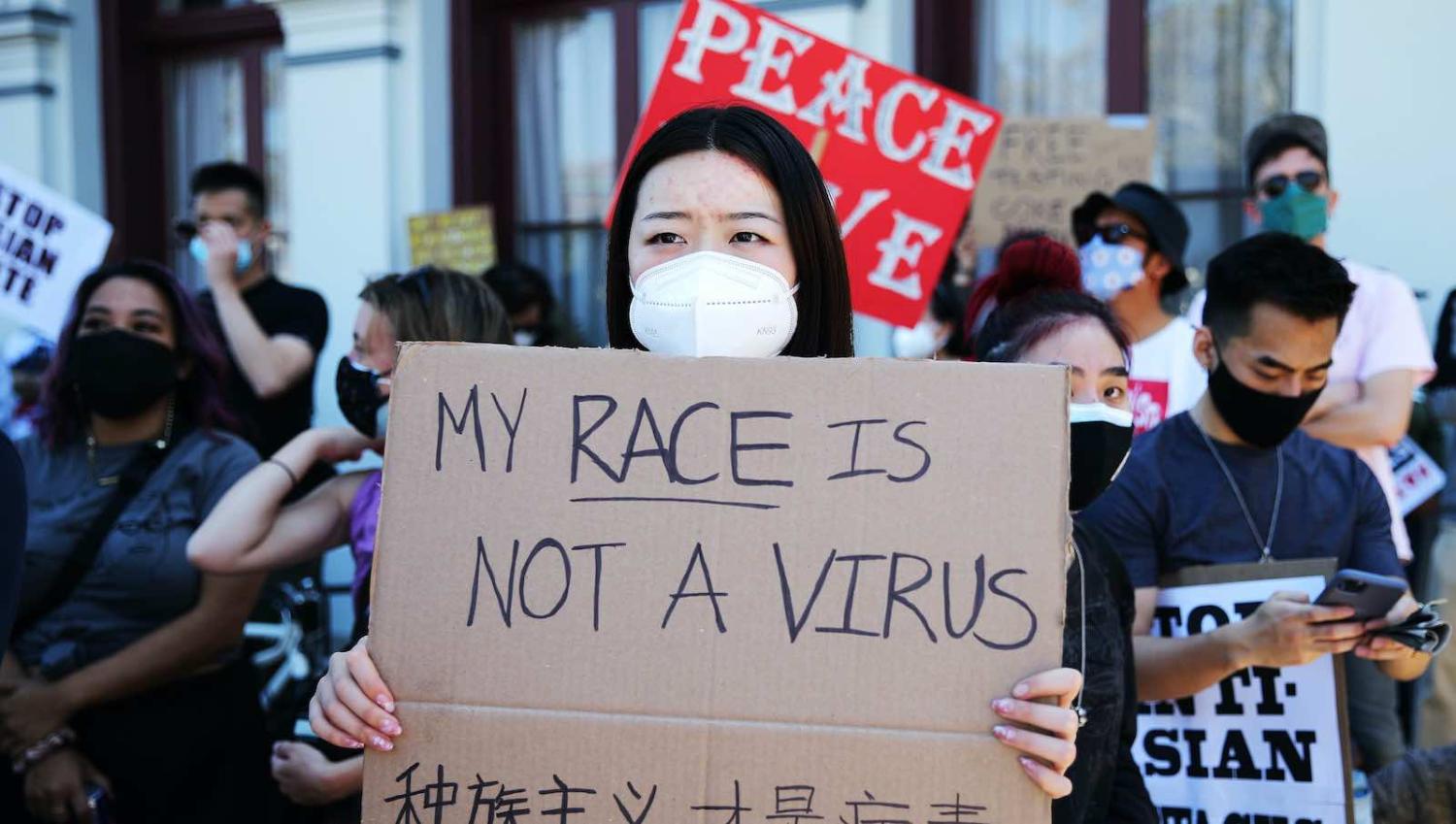

These findings echo a larger narrative about the rise in anti-Chinese and more broadly anti-Asian sentiment in the Covid-19 context. Originating out of Wuhan, China, the Covid-19 pandemic instantly became associated with China and Asia more broadly, and this appears to have led to increasing instances of discrimination against people of Asian descent. Numerous news reports highlighted racist incidents and, in extreme cases, violent attacks against Asians. While stereotypes linking Asians with disease are not new, especially during epidemics, the origin of Covid-19 became deeply politicised, once again bringing about scapegoating of those of Asian descent.

Despite the wide media coverage, however, there is very little data available to provide a more detailed picture of who expresses racial prejudice. This link is crucial to any efforts to stop it from continuing.

To fill this critical gap, we fielded surveys on the YouGov online panels in Australia and the United States in September 2020. The surveys were designed to collect representative samples of 1,375 adults in Australian and 1,060 in the United States.

The central difficulty of exploring racism in academic research is the potential presence of social desirability bias – when asked directly, people may conceal their opinions in order to conform to social norms. In our study, we sought to reduce this potential bias by including direct and indirect (list experiment) questions to ask about respondent’s attitudes towards Asians.

Specifically, using direct questions, we asked respondents to rate how worried they are about catching Covid-19 from Asian Australians/Asian Americans, white Australians/white Americans, and African Australians/African Americans. In the list experiment, we randomly assigned respondents to either a control or treatment group. The control group was presented with four venues: (1) Italian restaurant, (2) nightclub, (3) gym and (4) Indian restaurant, while the treatment group also had a fifth item: (5) Chinese restaurant.

Despite Australia’s much lower infection rate, higher proportion of Asian diasporas and a smaller economic recession, the population shows a slightly greater worry about catching Covid-19 from Asian Australians, compared to their American counterparts and how they view Asian Americans.

Importantly, respondents were not required to say whether they felt concerned about each venue but were asked only how many venues they avoided for fear of Covid-19. In this way, the sensitive question was asked in an indirect manner with the aim to elicit more representative responses. Admittedly, this sensitive item we included in this survey (i.e., Chinese restaurant) may not represent the broad Asian population. However, the political rhetoric around Covid-19 was deeply anti-Chinese and thus, we used this option to capture whether this sentiment was internalised by the broader population.

We then linked these responses to key socioeconomic factors including political affiliation, age, gender, education, employment status, and income, to identify the characteristics of those who are more likely to express racial prejudice.

Our analysis draws several key findings. First, despite the much better control of the disease spread, Australians are slightly more worried about catching Covid-19 from Asian Australians. In direct questions, Australians expressed a higher level of anxiety about catching Covid-19 from Asians averaging 2.74 out of 5, compared to 2.53 among Americans (a statistically significant difference). Similarly, the list experiment suggests that 46% of the Australian respondents would have avoided Chinese restaurants for fear of Covid-19, compared to 39% in the United States (a difference not statistically significant).

Second, in the United States, the most significant predictor of anti-Asian bias is political affiliation. In Australia, the picture is more complex – anti-Asian bias is linked to a wide range of socioeconomic factors including political affiliation, age, gender, employment status, and income.

Finally, while the list experiment largely confirms many findings from direct questions, they also indicate important and interesting differences. When asked directly, we find few differences across age, gender and employment, indicating most Australians do not report racial bias in who may be disease carriers. However, when asked indirectly through our list experiment, we find that younger people, women, and the employed were significantly more likely to avoid Chinese restaurants under Covid-19. The contrast between the two sets of findings points to the potential presence of social desirability bias and suggests some of the anti-Asian bias may be unconsciously internalised.

Our findings demonstrate the complexity involved in anti-Chinese and more broadly anti-Asian sentiment under Covid-19. For Australia, the worrying sign is that despite a much lower infection rate, higher proportion of Asian diasporas and a smaller economic recession, the population shows a slightly greater worry about catching Covid-19 from Asian Australians, compared to their American counterparts.

Anti-Asian sentiment is unevenly shared across different demographic groups. However, many may not choose to express their racial prejudice explicitly. Combined, these findings point to a need for more substantial efforts to document and address the long-held biases from a history of Chinese and Asian exclusion, as many others have advocated.