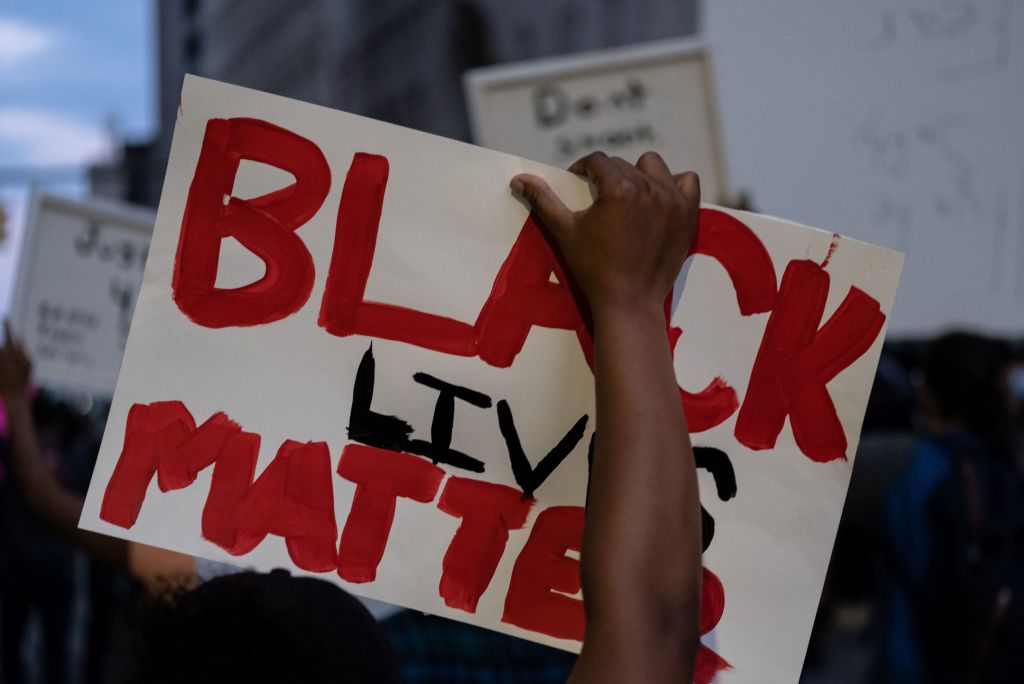

The death of George Floyd during an arrest by a Minneapolis police officer has set off a wave of protests across all 50 states of America. Even during an ongoing pandemic, the protests have been extensive and sustained. But these protests are not unique. Unfortunately, neither is George Floyd’s death. African Americans have been dying at disproportionate rates at the hands of US law enforcement for decades.

So why is it that seven years after the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement do we still have a problem with police misconduct and excessive force within US police departments? Despite sustained public protest, police body cameras and viral mobile-phone footage highlighting instances of abuse that would normally have gone unnoticed, as well as an increasing number of political leaders and police chiefs publicly committed to police reform, including mandating racial sensitivity and de-escalation training, 1252 black people have been shot and killed by police since 2015, according to one estimate.

One underexamined but central reason is the power of police unions. Because police unions are able to negotiate exceptionally protective contracts for their officers, they have become more influential than police commanders. State and local governments allow police officers to collectively bargain over the terms of their employment, so it means that unions are also allowed to bargain the extent and content of internal disciplinary review and procedures. They set the tone for police culture and have been able to strong-arm elected officials and obstruct police reform in the name of labour rights.

What happens when protecting a police officer’s labour conditions becomes a matter of impeding public safety?

Bob Kroll, the Trump-supporting head of the police union in Minneapolis where Floyd was killed, has become the most recent symbol of obstructionist police unions. Kroll has called the protests a “terrorist” movement and wrote a letter to his members defending the actions of Derek Chauvin, the officer charged with Floyd’s death, and the other officers involved in the arrest, confirming that union lawyers are representing the four officers who were fired. Kroll also took the opportunity to criticise the “lack of support at the top”, stating that elected officials were “minimising the size of our police force and diverting funds to community activist with anti-police agenda”.

Former Minneapolis police chief Janee Harteau responded not only by criticising Kroll for standing up for Chauvin, but to detail the many ways that Kroll and the Minneapolis Police Officers’ Federation’s board had obstructed her attempts at reform. Retweeting a news article that revealed that Chauvin had 18 prior complaints of misconduct, Harteau confirmed that the union was her biggest obstacle in making lasting changes within the Minneapolis police department. She said Kroll’s letter was “another example of why unions and arbitrators must be held accountable and support the discipline decisions of police leadership”.

The problem with police unions does not stop in Minneapolis. Police unions across the US have consistently stood in the way of reform efforts and obstructed accountability.

In 2017, a Reuters report examined police union contracts and found that unions play a critical role in “using [their] political might to cement contracts that often provide a shield of protection to officers accused of misdeeds”. The report also detailed how police unions will sustain campaigns against reform minded city officials and police chiefs if they threaten their ability to shield their members. A separate scholarly examination of 178 police union negotiated contracts in the US also demonstrated how unions have frustrated efforts at police accountability and reform.

Advocacy organisations such as “Campaign Zero” have also found many police unions negotiated rigid contracts that restricted the ability of police chiefs and civilian oversight bodies, when they do exist, to investigate police misconduct and crime. Their analysis of 81 union contracts in major US cities identified a number of stipulations that hinder oversight, such as ones where an officer involved in a shooting cannot be interviewed at the scene. Contracts often include clauses that require the city to pay costs related to investigation such as putting officers on paid administrative leave and paying for legal fees. Other contracts stipulate that complaints against an officer are disqualified if they are submitted too many days after an incident or place limits on the interrogations of police officers when investigated.

Many police unions in the United States have also been able to negotiate favourable arbitration agreements in their contracts that have allowed officers found to be guilty of misconduct to be reinstated. Other clauses allow past incidents of misconduct to be erased from an officer’s record in as little as two years after an incident.

Police unions in the US frame this as an issue of protecting labour rights and due process. They argue that if everyone who finds themselves on the wrong side of the law filed a police complaint and it led to the dismissal of that police officer, cops would not be able to do their job.

But what happens when protecting a police officer’s labour conditions becomes a matter of impeding public safety? It’s clear that police officers are able to evade accountability because of the contract stipulations their unions negotiate for them.

Police unions’ negotiating power stems from the fact that have a great deal of political clout – they have a large membership base and are generous campaign donors to both democratic and republican campaigns. Local Democratic-led administrations don’t want to be against a public sector union. Local Republican governments that run on a “law and order” platform are willing to support anything that would strengthen greater police authority.

And while police unions have managed to negotiate pay that makes police one of the highest-paid public sector positions, unions have also traded away additional salary increases and presented them as budget saving concessions to local governments which local politicians can then sell as fiscal management measures. But the unions have demanded greater autonomy and less oversight of police forces in exchange.

Police unions are one of the few unions to buck the international trend. As unions in neoliberal democracies have weakened, police unions have maintained their position and become stronger. But as a result, police unions have constructed the largest barricade to police accountability and reform.