If Australia’s economic future lies in Asia, then managing the risk of financial crises in the region should be a top concern. Especially as any crisis could also have significant geopolitical consequences.

In an analysis for the Lowy Institute, Barry Sterland looks at what Australia can do about this. It raises some interesting issues about how Australia can best pursue such interests in a changing global environment.

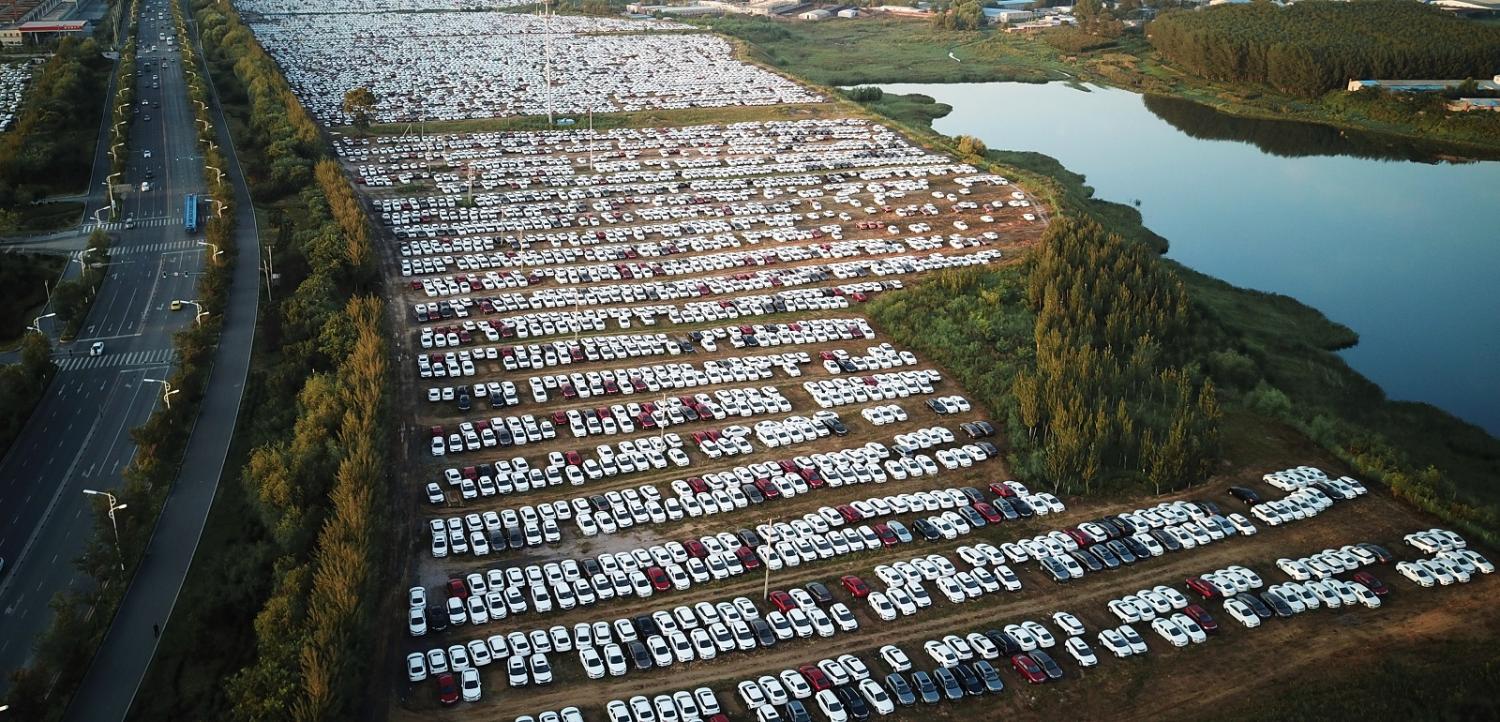

A quick scan across Asia reveals that macroeconomic fundamentals are mostly pretty good. However, China, where risks have been building for some time, is the big exception. A crisis in China is still a tail risk at this point. But even if China’s risks eventually abate, new threats will undoubtedly emerge over time.

A fragmenting financial safety net

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is intended to be the global economy’s financial safety net. But its central role in managing crises is diminishing and the system is becoming more fragmented.

When the global financial crisis struck, it wasn’t the IMF but rather the US Federal Reserve that acted as lender of last resort to the world’s major economies. In Asia, only a few had access to the Fed’s dollar swap lines. But others were able to rely on their own large stockpiles of hard currency reserves as well as ad hoc bilateral arrangements to weather the shock.

In Europe, where deeper crises set in, the IMF did get involved. But even here, within the so-called ‘troika’ it was relegated to junior partner to the European Commission and European Central Bank. This marked an important departure from normal practice where the IMF typically serves as lead crisis manager.

A central issue is the IMF’s legitimacy problems. Larger emerging economies have systematically avoided it since the crises on the late 1990s and continue to search for viable alternatives. This is especially true in Asia where bitter memories of the Asian financial crisis persist. The Greek debt crisis has since only reinforced perceptions of undue political influence in IMF decisions and policy prescriptions.

Since 2008, the scale and number of central bank currency swaps have continued to expand, estimated to have a total value of US$1 trillion (similar to the IMF’s total lending capacity); and that is without including the Fed’s unlimited swap lines with several advanced economy central banks.

Regional financial safety nets have also been further developed. In Asia, the Chiang Mai Initiative was strengthened in important ways, including by multilateralising and substantially increasing its commitments, de-linking more of its financing from the IMF, and establishing the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) to provide support akin to the IMF’s technocratic role.

No going back

Sterland suggests that Australia should, in the first instance, advocate for a more integrated global financial safety net centred around a strong IMF but also plan for operating in a second-best world. Unfortunately, we are more likely to be facing the latter.

Rebuilding the IMF’s legitimacy and ensuring it has adequate lending capacity are essential. However, the incumbent powers are reluctant to give up their dominant positions to make room for emerging economies, notably China, and securing additional financial commitments is always difficult.

Yet, even if these issues are resolved, it is unlikely to reverse the trend towards greater fragmentation. The IMF will remain important, particularly for dealing with deeper crises. But it risks becoming less central and an increasingly last resort.

For instance, while China undoubtedly wants more influence at the IMF, it is also clearly interested in developing alternative mechanisms, preferably ones that give it more influence.

Chinese currency swaps have rapidly expanded, now totalling US$550 billion, and this will likely accelerate. China has also been active in developing alternative multilateral mechanisms, including the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM) and the Contingency Reserve Arrangement amongst the BRICS.

One can draw an instructive parallel here with China’s approach to official development financing, where it focuses heavily on direct bilateral financing, secondarily on China-led multilateral development banks, and lastly on seeking more influence at the World Bank.

Meanwhile, within Asia more broadly there is likely to be a growing desire for alternatives to the IMF. Not only does the region continue to attach a negative stigma to the IMF, but as Asia grows richer it will naturally want, and be able to afford, to have a stronger say over its own affairs, including how crises are managed. To see this, one need only look at how Europe chose to lead its own regional crisis response and establish the European Stability Mechanism.

There are thus likely to be continued calls to further strengthen the CMIM and move it further along the spectrum towards the Asian Monetary Fund idea that Japan initially floated in the late 1990s. The CMIM still has a long way to go and there are important questions about its operational readiness. But the direction of travel seems clear.

The US for its part has closed its swap lines to emerging economies and resisted calls to institutionalise a Fed role as international lender of last resort. Yet, in the event of another major international liquidity crisis, it may well be compelled to step in again.

What should Australia do?

Australia thus increasingly needs to be able to work within a more fragmented architecture. This will require us to be more engaged and proactive. Importantly, despite our limited financial firepower, the marginal value of Australian support during a crisis could be higher in this context, if we can respond flexibly and quickly to unfolding crises.

Sterland’s suggestions to strengthen Australia’s operational readiness and revisit the legal and policy framework guiding Australian crisis support are thus worth considering. Particularly the idea of removing the need for a request from the IMF (or another multilateral) for Australia to provide financial assistance. This could greatly facilitate the ability to provide the kind of early support that can help contain a crisis.

Prevention, through better policies in Asian economies themselves, is of course better than cure. Sterland’s suggestion here is to focus on policy dialogue through various international forums and also bilaterally.

Another tool that could be more actively tapped are technical cooperation programs, of the kind typically funded under the government’s overseas aid program.

Indonesia is a good example, where Australia has been doing this for some time and having good influence – helping Indonesia get through the 2008-09 crisis and the 2013 ‘taper tantrum’ relatively well.

Technical cooperation programs like this could be extended to other countries in the region. Importantly, this needn’t be restricted to those eligible for our aid, but rather based on our interests in maintaining regional economic stability. One option would be to extend such support on a regional basis, perhaps working with AMRO which would allow us to both strengthen an important nascent institution and deal us more into regional stability discussions, without necessarily joining the CMIM.

Such work would need to be closely integrated with the enhanced policy dialogue by economic officials that Sterland suggests to ensure it is as effective as possible and the two are not operating in silos.

Australia’s influence with Asian policymakers will be much higher if we also offer support to actually devise and implement the reforms needed, and also if our own views are informed by an appreciation of the complexities faced in these generally less developed and more difficult institutional environments.

As a small economy with key interests in the region, this could be worth the added investment.