The way incessant talk of China’s rivalry with the United States dominates the present turbulent world, it’s hard to conceive of an earlier time when Australia’s prime ministers devoted hours upon hours to the fate of far-off Zimbabwe. But the death on Friday of African independence hero-turned-tyrant Robert Mugabe was a reminder that in the days before the G20, APEC, or the East Asia Summit, the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting was Australia’s seat at the high table.

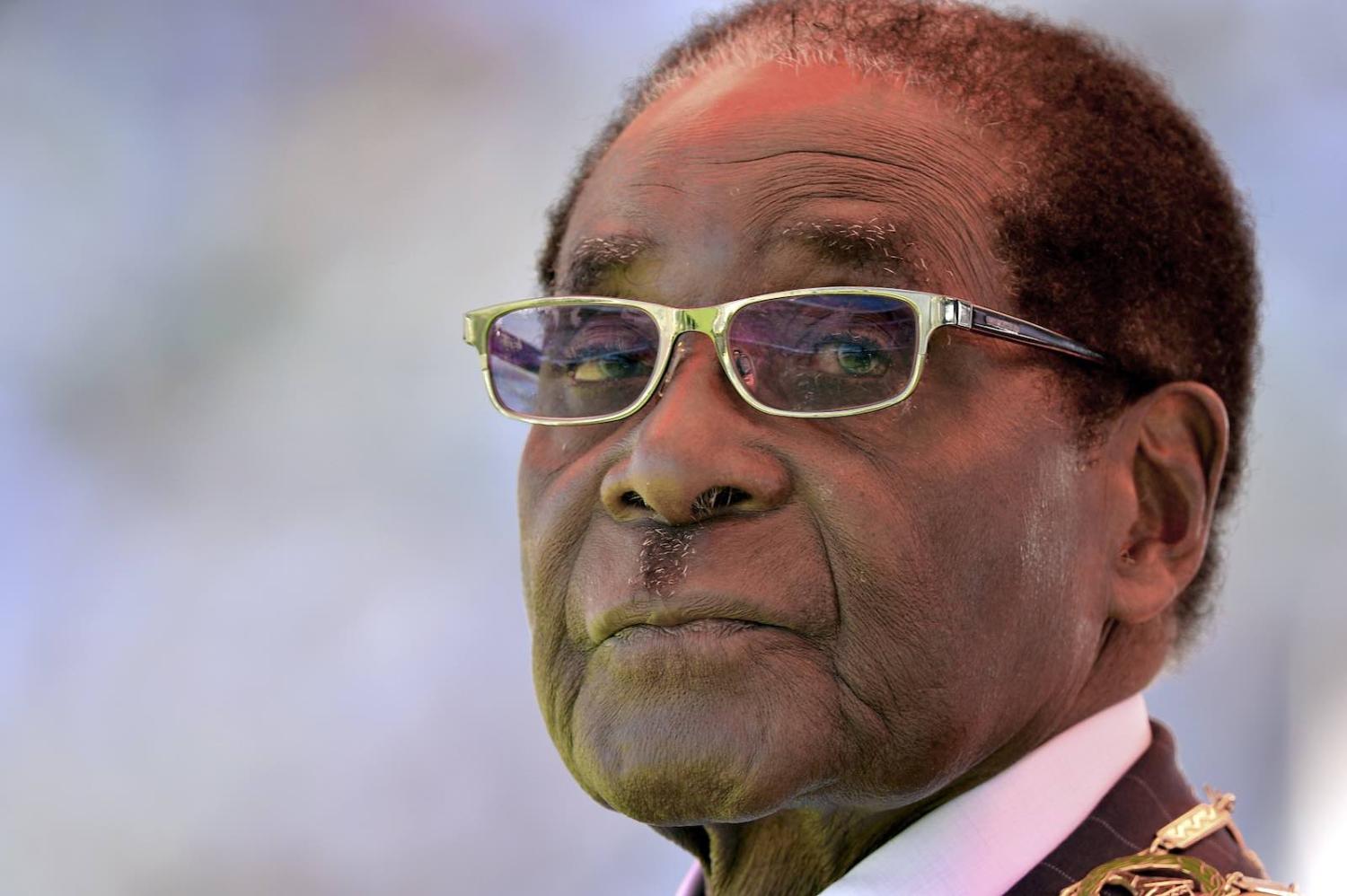

Robert Mugabe died at 95, having ruled Zimbabwe for nearly four decades, a time spanning nine Australian prime ministers.

And it was at CHOGM that debate was so often dominated by Zimbabwe’s painful and bloody transition from white rule as Rhodesia in the late 1970s to the eventual recognition of the Mugabe regime’s vicious character in the early 2000s. Australia’s Malcolm Fraser played a key role in Commonwealth negotiations leading up to the 1979 Lancaster House talks and Zimbabwe’s independence, while John Howard was a member of the so-called “troika” with counterparts from Nigeria and South Africa in 2002 that saw Zimbabwe suspended.

Nelson Mandela once offered the most fitting epitaph for Mugabe – that “he was the star, and then the sun came up”. Yet charting the remarks by successive Australian leaders across the past 40 years via the superb online database PM Transcripts also captures the way hopes for Mugabe’s rule gradually withered and the sorrowful cost to the people of Zimbabwe as he transformed into one of Africa’s longest-reigning despots.

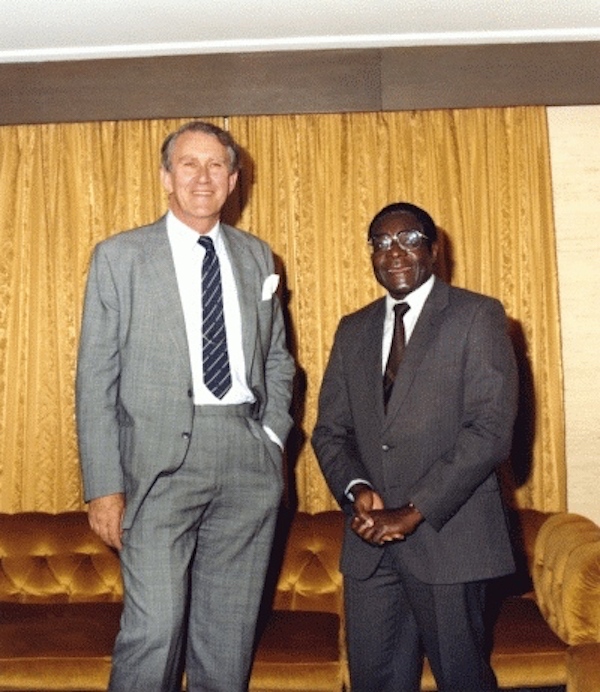

Malcolm Fraser flew into Harare on 18 April 1980 to celebrate Zimbabwe’s independence and issued a statement displaying a faith in democracy that would prove hard to dispell.

During my meeting today with Mr Mugabe, Prime Minister of Zimbabwe, I said that Australia warmly welcomed Zimbabwe’s independence and looked forward to the development of a constructive and many-sided relationship with Zimbabwe … Australia wishes Mr Mugabe every success in the difficult task ahead of him … Australia is pleased to have been able to play some part in Zimbabwe's progress to independence, through consultations with African and other leaders …

I also informed Mr Mugabe of an Australian Government gift of two despatch boxes for the Senate Chamber of the Zimbabwe Parliament. This gift will symbolise the bond between the two countries as constitutional democracies with a common system of institutions which I believe will facilitate co-operation over a wide range of activities.

A year later, Fraser hosted CHOGM in Melbourne, welcoming Mugabe as an honoured guest, praising the independence of Zimbabwe as “one of the Commonwealth’s great successes”, and dismissing the prophets of “gloom and doom” who predicted “that the Commonwealth would break on the rock of the Zimbabwe problem”.

Although in a sign that all was from from settled, Fraser had to bat away questions from press gallery stalwarts Michelle Grattan and Paul Kelly about Zimbabwe’s turn away from the West.

I was speaking to somebody the other day who has got family connections in Zimbabwe and his view was that there is a very high regard for what Robert Mugabe is seeking to do and a high regard for what he has so far achieved in Zimbabwe.

And he was quizzed by a talkback caller on radio on the “Marxist Mugabe” and the protracted race issue:

The assistance he gets he wants to come from English-speaking countries, which is one way of saying he does not want too many Russian communists around. He has done many things to try and make sure that the white people stay in Zimbabwe. When I was there for independence day celebrations, the white people were looking to the future with a sense of confidence and optimism.

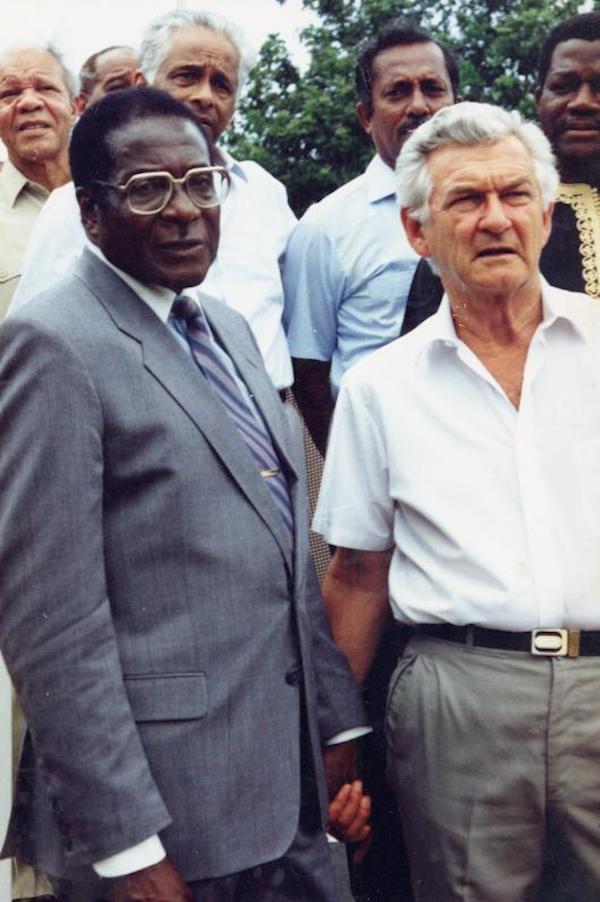

Fraser was hardly a lone optimist. By the time Bob Hawke visited Harare in 1991 when Zimbabwe had its turn hosting CHOGM, there was still hope in Mugabe. As Hawke told parliament on his return:

I was heartened by the commitment to multi-party democracy in Zimbabwe which President Mugabe evinced in our discussions … Zimbabwe offers growing opportunities for Australian trade and investment. I was glad to obtain from President Mugabe his assurance that he would take a personal interest in the negotiations at present underway.

While historians such as Heidi Holland in her excellent Dinner with Mugabe now tell that the West allowed itself to be wilfully ignorant of the early signs of Mugabe’s oppression, even in the mid-1990s the experience with Zimbabwe was still regarded as a success. As Paul Keating put it:

The Commonwealth’s moral authority has been important in Zimbabwe.

Back then, cricket was the most obvious connection for Australia to Zimbabwe, particularly in the early years of self-described cricket tragic John Howard. Yet the forced evictions in Zimbabwe of white farmers from their properties in the late 1990s and the blatant rigging of elections swept away any lingering pretence of Mugabe’s democratic commitment. Zimbabwe had boasted more than five million head of cattle in 1998, yet five years later, only 250,000 remained as the country spiralled into economic ruin. Howard was asked in 2000 whether he would be open to accepting Zimbabwe farmers as migrants:

Of course we are open to considering the position of any group of people who might fall into the category of refugees. We are obviously, like everybody else, disturbed at the apparent breakdown in law and order, the apparent disregard for the authority of the courts that is now occurring in Zimbabwe.

Mugabe avoided a direct showdown with Commonwealth leaders after the 2001 CHOGM to held in Brisbane was delayed until the following year. But after another sham Zimbabwe election in March 2002, Howard joined the troika to pass judgement, which eventually saw the regime suspended from the organisation. The focus was intense. Even as the world reeled from the 11 September 2001 attacks and as momentum gathered for the invasion of Iraq, Howard would be asked about Zimbabwe at least 60 times in press conferences and in public over the coming months, also travelling overseas extensively for consultations.

But frustration built after now-declared President Mugabe quit the Commonwealth in spite and simply ignored international pressure. The contrast with early optimism for independence could hardly have been more stark, as Howard described the situation in a speech to the Commonwealth Round Table in 2003:

Conditions in Zimbabwe have continued to worsen both politically and economically. Human rights are routinely violated as President Mugabe’s regime seeks to silence all opposition. Freedom of expression is suppressed by violence … Inflation is currently running at 455%. The cash economy has virtually halted due to an acute shortage of cash and foreign exchange …

Australia has tried very hard to bring about change in Zimbabwe … But President Mugabe’s regime continues to encourage systematic harassment and torture of the opposition, electoral malpractice and corrupted legal processes …

The regime of President Mugabe is only in power because, through a campaign of violence and rorting, it stole the presidential elections in March 2002.

And that same electoral theft was repeated in 2007, with Howard using a weekly radio message to deplore hyperinflation under Mugabe, which by then had reached 1800%, alongside an unemployment rate of 80%, leaving Zimbabweans with “the lowest life expectancy of any country in the world”.

This dismal assessment of Zimbabwe’s prospects was soon echoed by Howard’s successor, Kevin Rudd:

Mr Mugabe has no political legitimacy at all. What we’ve seen is the destruction of democracy in Zimbabwe. And Mr Mugabe’s legitimacy should be challenged by the entire international community, and not just by Australia.

And repeated by Julia Gillard, attempting to offer some measure of solace to Mugabe’s opponents, who struck an invidious power-sharing deal with the tyrant:

More than 30 years on, Australia remains a firm friend of the Zimbabwean people as they continue their long struggle for peace and democracy.

While in the Abbott-era, Zimbabwe’s then-ambassador to Australia took the extraordinary step of requesting asylum rather than returning home.

But with every tyrant comes the fall, as so in November 2017 Mugabe finally lost his grip on power. Malcolm Turnbull captured what had by then become a resigned sense of disappointment in Mugabe’s brutal rule, and also the way Australia’s priorities had moved elsewhere:

He’s been a dictator that’s committed horrific crimes over a long period of time. You know, again, it’s not for me to engage in what’s going on there in Zimbabwe, but the reality is he was the independence leader, that’s true, all those years ago, but it has been a very oppressive and brutal dictatorship for a long time.

“Better off without him?”, Turnbull was asked.

Well it depends what he’s replaced with, I suppose … it’s a tough part of the world. But he certainly – it is not a model of liberal democracy, put it that way.

Robert Mugabe died at 95, having ruled Zimbabwe for nearly four decades, a time spanning nine Australian prime ministers.