This year, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Committee called for a “paradigm shift” towards the acceleration, innovation, and mobilisation of equal and inclusive leadership in global decision-making. Over four decades after CEDAW came into effect, no state has yet satisfied the fundamental rights guaranteed in Article 7 and Article 8: eliminating discrimination against women in politics and public life and ensuring equal representation of women in government at the international level.

Not only does women and gender minorities’ under-representation on the global stage maintain and deepen inequalities, but there is also evidence that deprioritising gender equality risks perpetuating some of the catastrophic risks we are aiming to prevent. This includes effective climate action, for example, hampering our ability to achieve a range of positive outcomes. It perpetuates a negative feedback loop of systemic discrimination and underrepresentation.

As someone who did their PhD on women’s leadership in international affairs (more on my new book here), I sometimes feel like this is an old conversation we’re having. But the fact that we are still having this conversation is indicative of the pervasive and continued challenges, which are occurring against a background of Covid-19 backsliding, cascading crises, and the rise of anti-rights advocacy that threatens progress on fundamental rights and leadership.

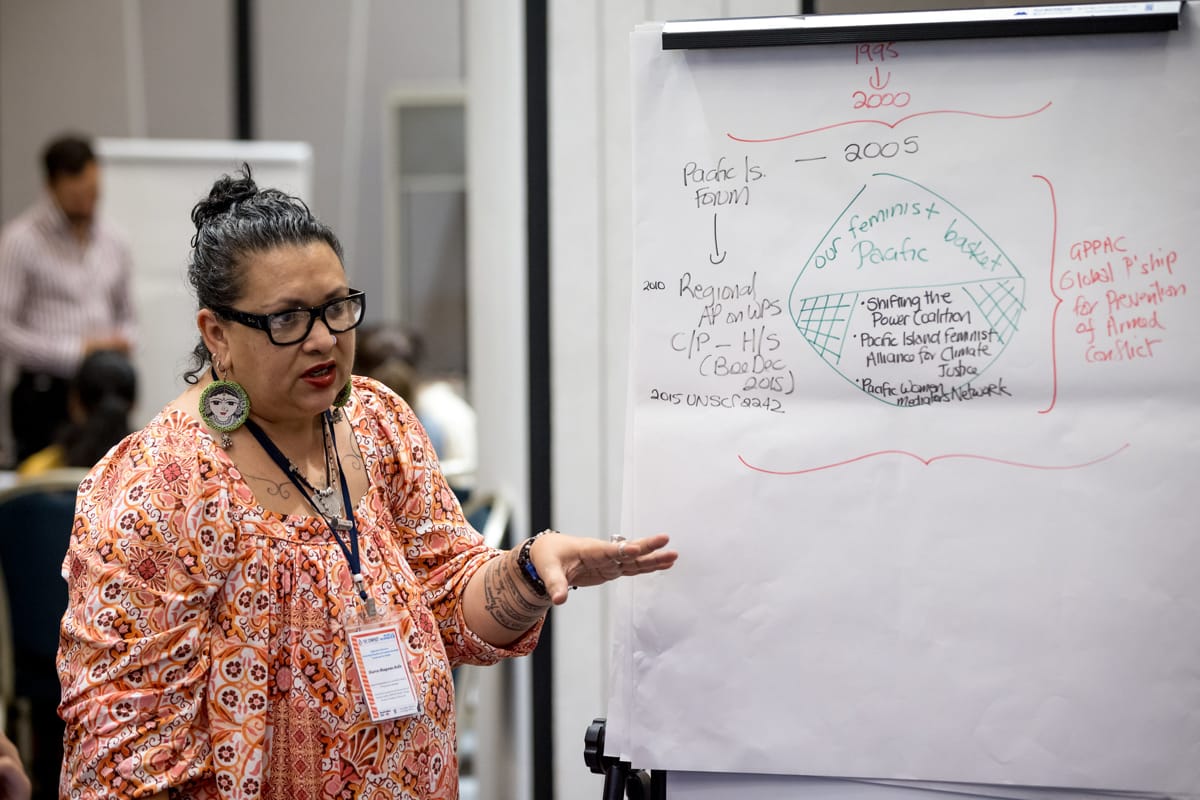

Women’s greater presence within foreign affairs is increasingly in evidence, alongside a wider push within foreign, defence and development policy towards gender equality. This is occurring through mechanisms such as the UN Security Council Resolution on Women, Peace and Security or commitment to feminist foreign policy, for instance.

Yet the campaign for representation of women in international tribunals and monitoring bodies GQUAL finds that women are under-represented across almost all bodies in charge of imparting or affecting international justice and human rights. My study also shows a diplomatic “glass cliff” for Australia, whereby women now have equal or near-equal representation in Australian diplomacy while the institution they represent has been on a shrinking/stagnating trajectory – despite recent funding boosts.

This glass cliff intersects with other trends, such as horizontal segregation whereby women tend to be siloed in “female-dominated”, so called “soft” portfolios (humanitarian affairs, HR), as well as challenges with posting internationally, navigating anti-rights, anti-feminist backlash, and online harassment and trolling.

The over-representation of men in institutions of security, policing, and defence combines with the “glass cushion” (aka “hot jobs”) men have access to in international decision-making. Typically, these “hard” jobs in international affairs are seen as the best qualifications for international peace and security work. The process of international nominations (for instance, to the international courts system) is also highly opaque, presenting issues in understanding the secret processes through which international leaders are cultivated.

I have written about the impact that this lack of transparency has on diversity in the intelligence sector, which goes beyond its impact on women (less jobs, harder to get). It also has implications on institutions’ accountability and social license to operate. If we don’t know how international representatives are chosen, it is unclear how we can ever accurately represent the nation on the world stage.

This is compounded by illiberalism, feminist backlash, and a global anti-rights agenda. Lowy’s Daniel Flitton recently pointed out that the group of leaders presently in power longest globally are men, while most dictators have been men, and dictators often embody and reinforce anti-rights, anti-feminist rhetoric and agenda.

Ultimately, CEDAW’s new paradigm shift isn’t really a new paradigm shift in principle. The goals remain mostly the same: addressing gender inequality. The paradigm shift is really in how to convert the obligations under CEDAW into tangible results for equal representation in decision-making. We are rights rich, but remedies poor. The question remains: what power does CEDAW have if everyone already agrees to the obligations but never achieves them?

To this end, more sophisticated interventions are needed, with more transparent processes and more accountability to obligations. Compliance matters.

There are many reasons why gender equality in leadership matters – moral and strategic reasons among them. For Australia, it helps to fulfil a representative democratic promise and ensure the equitable contribution (and benefit) of all members of society to fields of strategic investment, opportunity, and risk. Gender equality in global decision-making has important ramifications for the health and strength of democracy, as legitimate political and international affairs systems rest on the consent of its citizens.

This “social license to operate” means that public policies and institutions are obligated to represent and make decisions on behalf of citizens, for the benefit of citizens – and gender (in)equality matters. Research demonstrates that gender equality increases social trust. Gender equality is not just a consequence of democracy, but at least theoretically self-evident to democracy: “if this majority (women) doesn’t have full political rights, the society is not democratic”.

Above all, inclusive and representative global decision-making is already a right Australia has already agreed to uphold through CEDAW. In an era of cascading crises and new frontiers, it has never been more important that we finally fulfil obligations to this right.