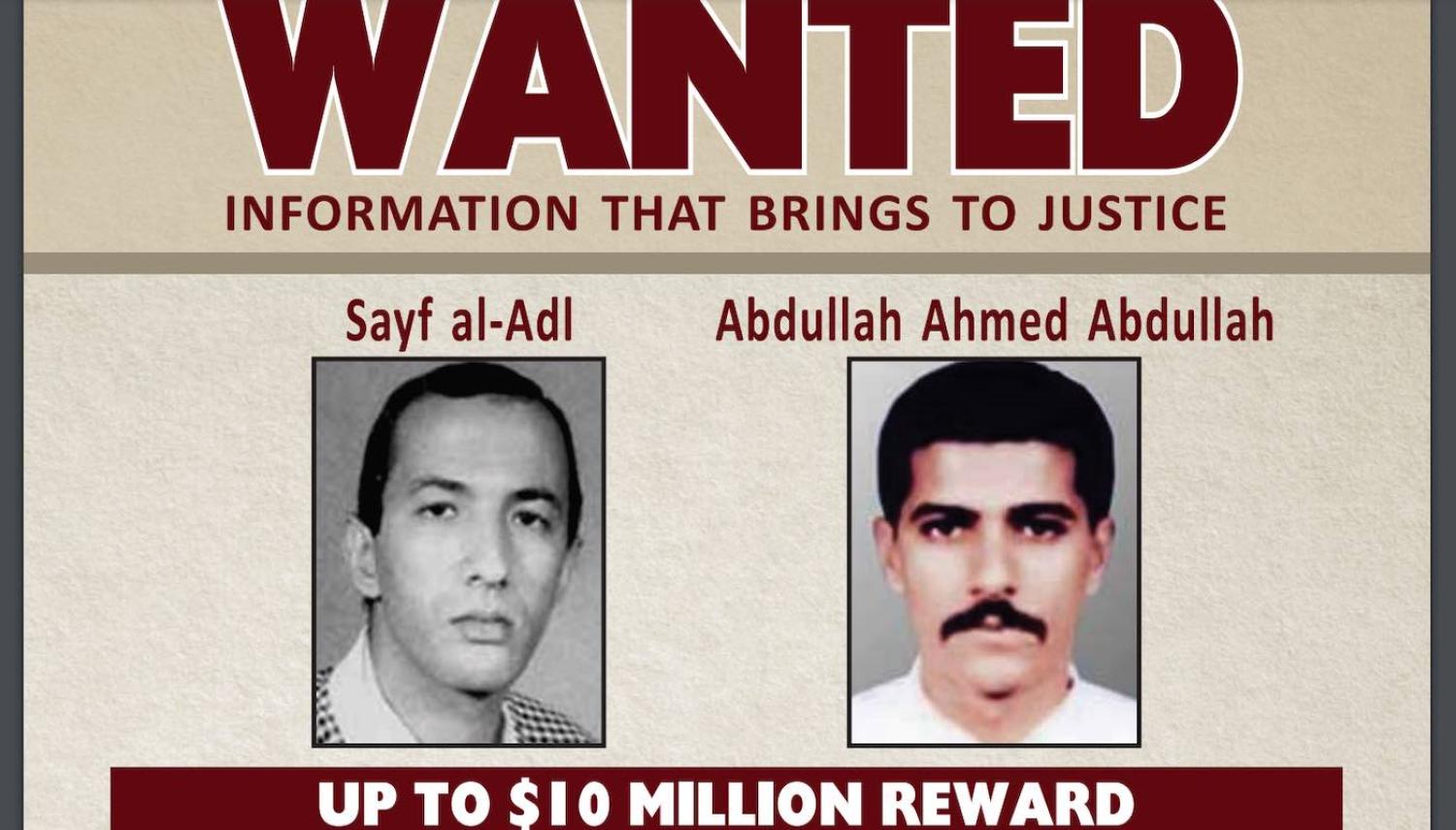

For year after year, the moustached face Abu Mohammed al-Masri has stared blankly from a photo on an FBI most-wanted poster. A founding senior member of al-Qaeda, al-Masri was responsible for the 1998 US embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania that left more than 200 dead. Also known as Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah, he’d been hunted ever since.

Until 7 August, when al-Masri was reportedly killed in Iran, along with his daughter Maryam, on the anniversary of the attacks he orchestrated in East Africa 22 years earlier.

News of his death has taken months to trickle out. The killing was first reported as an Israeli assassination against a man called Habib Dawoud – an academic with ties to Hezbollah. But it didn’t take enterprising regional journalists long to figure out that there was no such Hezbollah associate by that name, and that the man who was killed in a drive-by shooting was in fact the senior al-Qaeda operative. There was an erroneous suggestion the strike had taken place in Afghanistan. Iran still denies the reports of his death, and neither Israel nor the United States has taken responsibility, although al-Qaeda has finally confirmed it.

Iran has played a significant role in keeping al-Qaeda’s fortunes alive by sheltering the al-Qaeda exiles from Afghanistan.

The intrigue around this reported assassination is consistent with the intrigue around al-Qaeda’s association with Iran more broadly. While the presence of senior al-Qaeda operatives and the bin Laden family in Iran has been widely reported, the nature of al-Qaeda–Iran association is still contested.

We do not know for certain whether – as has been previously reported by the United Nations and other government bodies – al-Qaeda members have been directing operations from within Iran and communicating with affiliate groups. Despite their natural antipathy, we also don’t know if al-Qaeda members and Iranian forces are in a “marriage of convenience” to pursue common enemies. And we still don’t know whether the al-Qaeda members are in close custody, curtailed in their activities by Iranian surveillance and control, as documents found in Osama bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound reveal, in a risky yet uncanny move by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps to stop the jihadist group targeting Iran.

Or could elements of each be true?

It is important to understand al-Masri’s death and the relationship that al-Qaeda members and their families have with the Iranian regime. These al-Qaeda members and their families are part of the old guard, the original cohort, “core al-Qaeda”, bin Laden’s immediate associates, who went into exile in Iran from Afghanistan. In turn, the fate of this original cohort – a fate at least partly controlled by Iran – is important to understanding the future of the movement. It is also critical to assess whether they are able to use their relationship with Iran – even given its contradictory nature – to project the authority and capabilities of the movement.

Al-Masri’s death takes on further significance because it is coupled with recent rumours around the death of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Rumours have swirled periodically over the years of Zawahiri’s demise, but this time there may be more to it. If both Zawahiri and al-Masri are dead, it leaves only Saif al-Adel – another long-standing member of the most-wanted list – as one of the few remaining connections to the original al-Qaeda leadership team that is in contention for leadership.

The deaths of the so-called “core” al-Qaeda members will accelerate and increase al-Qaeda’s decentralisation and localisation.

Yet this does not make the core al-Qaeda members who remain in Iran or who have used it as a base irrelevant, not least because they have offspring they have incorporated into the movement and groomed for leadership. Media have reported al-Masri’s daughter was also targeted for her involvement in terrorist plots.

Will this next generation remain in Iran as well? And if they do, will they be constrained by IRGC monitoring? Or will they, like al-Adel, be able to use Iran as a base to travel to other jihadist hotspots (he reportedly travelled to Syria around 2016) so as to revive the dwindling connection of al-Qaeda’s core to affiliates in Syria, as well as Africa and Asia?

Iran has played a significant role in keeping al-Qaeda’s fortunes alive by sheltering the al-Qaeda exiles from Afghanistan. According to analyst Seth Jones, so long as al-Qaeda adhered to a number of red lines – to “refrain from plotting terrorist attacks from Iranian soil, abstain from targeting the Iranian government, and keep a low profile” – al-Qaeda operatives would be able to fundraise, organise, communicate and facilitate travel through Iran. Under pressure from the West through assassinations targeting its own, including IRGC head Qassem Soleimani and more recently chief nuclear scientist Muhsen Fakhrizadeh, punishing sanctions and with the future of the nuclear deal in doubt, Iran has even more incentive to hold on to its al-Qaeda wildcard.

But al-Masri’s assassination demonstrates that the al-Qaeda cohort in Iran does not remain beyond reach.