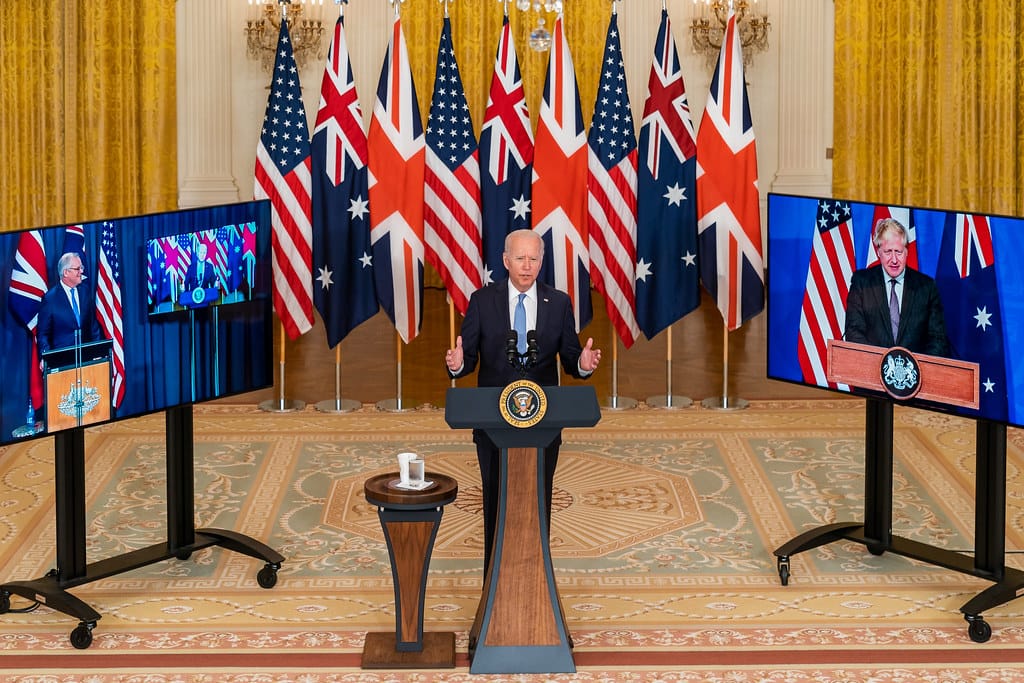

On 15 September 2021, Prime Minister Scott Morrison joined his British counterpart Boris Johnson and US President Joe Biden to announce AUKUS. In so doing, Morrison set Australia’s foreign and defence policies on a profoundly new course, a course now firmly embraced by the new Labor government led by Anthony Albanese.

The ambition of this deal, the outright hubris of it, still shocks. First, there is the implausibility of Australia getting nuclear-powered submarines in time to avoid a gap between the retirement of the existing Collins-class boats and their replacements. Whether Australia buys from a British shipyard or from the Americans, there is still no clarity about how this is going to get done.

There is hubris too in the military strategy implicit in the AUKUS deal. If the submarines are all delivered, Australia will join the high table of the world’s military powers. Nuclear-powered submarines are the apex predators of naval warfare and Australia is proposing to acquire at least eight, more than the UK and France now have, or plan to have. Nuclear power gives these submarines almost infinite range and endurance, and they will carry missiles that can strike targets thousands of kilometres inland. For the first time in its history, Australia will have global strike capability.

Above all, AUKUS is a profound step because of what it says about the Australian government’s attitude to the US alliance. AUKUS is a big bet on America and its commitment to compete with China for leadership in Asia. It ties Australia more closely than ever before to America’s military strategy for the region and makes it harder for Australia to back away if it doesn’t like the direction that the United States is taking.

The Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Coordinator and key US official behind AUKUS, Kurt Campbell, spoke in November 2021 of a “deeper interconnection, almost a melding of our services”. In a speech in Washington in July, Defence Minister Richard Marles used strikingly similar language when he said he wanted US and Australian forces to “move beyond interoperability to interchangeability”.

In that light, is it plausible to think Australia would ever withdraw its submarines from the fight if the US went to war with China? AUKUS ensures that this decision will already have been made.

It’s no wonder Biden embraced Morrison’s plan at the G7 meeting in Cornwall in June 2021. Morrison was proposing to spend what might eventually amount to $171 billion in the US arms and shipbuilding industries. And at the end of it, Australia will get a submarine fleet that will effectively serve as an adjunct to the US Navy. From Biden’s perspective, what was not to like?

And let’s linger for a moment on the date of that G7 meeting – June 2021. We know Morrison’s pitch was preceded by intense diplomacy with senior White House officials, which means the idea was likely first raised with the new administration in March or April. That’s only two or three months after the 6 January riot at the US Capitol. The paint would barely have been dry on the repairs made to the cradle of American democracy, yet here was Australia proposing to double down on the alliance with a deal that will take decades to fully realise. It was as if the Trump administration had never happened and could never happen again.

A year on, it is hard to think of a major defence or foreign policy initiative in living memory with such a stark divergence between what the public knows and what the government and its officials know. Inside the system, there is furious activity. The government has created a Nuclear Powered Submarine Taskforce with participants from ten government agencies. The Prime Minister’s Department has a branch devoted to nuclear-powered submarines and naval shipbuilding. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has an AUKUS taskforce.

But what has the Australian public learned about AUKUS that we didn’t know a year ago? No document has been released detailing the nature of the agreement. Neither this prime minister nor the last has addressed parliament on the issue.

Australians deserve to hear the detail. And more importantly, Australians need to hear from their government about how these submarines fit the nation’s military strategy and identity. Australia has always been a loyal US ally, but it has never before placed itself at the forefront of US planning for a confrontation with a superpower. And it has never before gone so dramatically on the offensive in its weapons acquisition, buying a weapon expressly designed to hem China’s navy in along its coastline and strike targets deep inside Chinese territory.

This is a question not just of military strategy but of how Australia defines itself as an international actor, and as a nation. Australians should be asking themselves: is this really who we are?