Australia’s new defence export strategy to transform the country into a top-10 global arms exporter raises many questions. This indicates that the government does not fully understand – or, at least, is yet to fully explain – the mechanisms behind the international arms industry and export market.

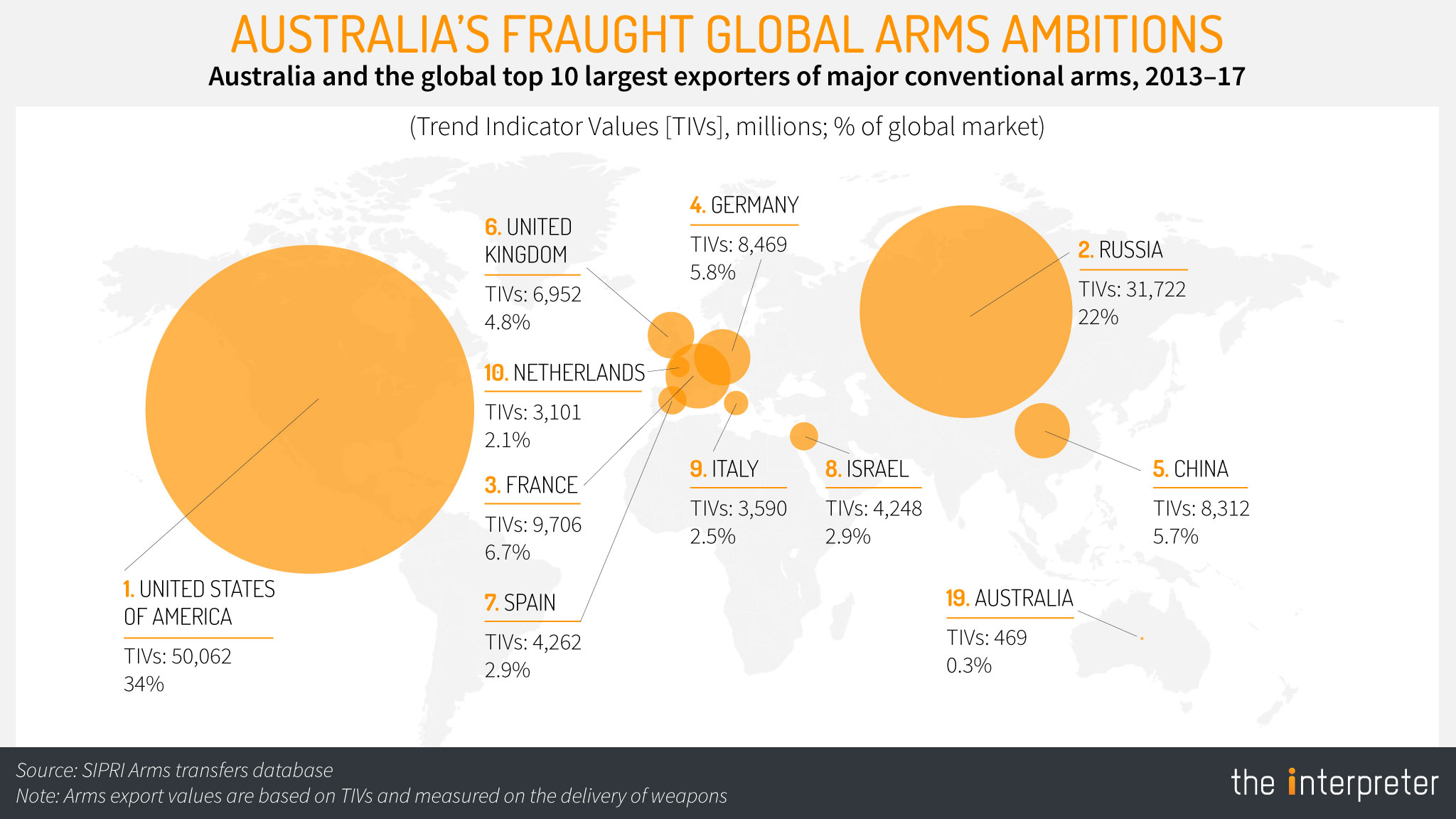

To understand the challenges of this ambitious goal, we need to understand the current standing of Australia’s arms industry, the country’s arms exports, and military expenditure. According to latest data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Australia currently spends $24.6 billion on its military (ranked 12th in the world for defence expenditure). Yet it has only one company in the top 100 international arms-producing companies, and its arms exports account for only 0.3% of global arms exports, ranking it 19th in the world.

The government indends to invest $200-billion in improving defence capabilities. While it is correct to identify that domestic demand is not enough to support the growth of its arms industry, becoming a major weapons exporter is often not in the control of the exporting country, but rather based on competition, demand, and bilateral relationships with other countries.

To become a recognised exporter, one needs a well-established arms industry. The government’s defence strategy report identifies industry success stories, such as the Thales Bushmaster, radars, and sonars.

But the problem is that each of these belongs to companies based in other countries with subsidiaries in Australia, such as BAE systems (UK), Thales (France), and Raytheon (US). These Australian subsidiaries produce under licence (or part of offsets from arms trade deals) to its parent companies, and generate limited technological or skills spillovers that help the development of a domestic arms industry.

The result is a need to develop a substantial locally owned arms industry.

Currently, the only locally owned company in SIPRI’s top 100 arms-producing companies is Austal, ranked 75th in the world, which mainly supplies troop transport ships to the US. However, about 93% of the company’s total arms sales are based in its US subsidiary, hence almost none of the production, skillstransfer, or job creation is in Australia.

Intra-industry innovation and skills spillover from locally owned companies are also very limited. This leaves open the question of how, where, and with whom Australia plans, in a 10-year goal set by the government, to establish arms companies capable of building high-quality conventional weapons.

Assuming that Australia can create a well-functioning local arms industry for export, who are its competitors? The market for armoured personnel carriers (for example, the Bushmaster) is already saturated, with more 40 countries producing and exporting them. As for the radars, the Active Phased Array Radars produced by CEA Technologies have mostly been deployed by the Royal Australian Navy, with limited exports to other countries. These radars, too, face stiff competition from established producers, such as Lockheed Martin (US) and Saab Group (Sweden).

Australia not only lacks a competitive advantage but also a comparative advantage relative to other arms producers and exporters. Countries such as China, Israel, Japan, South Korea, Britain, and the US, which produce cheaper weapon systems than Australia, are formidable current and future competitors. In addition, all these countries already have larger arms exports and industries than Australia. Other likely competitors, such as South Korea, have spent more than 30 years developing a competitive arms industry. Ten years is hardly long enough for Australia to become competitive.

If Australia is to break into the top-10 global arms exporters, it needs an almost sevenfold increase in its exports, and to overtake exporters such as South Korea, Sweden, Turkey, and Ukraine. As it currently stands, the top three importers of Australian arms are the US, Indonesia, and Oman, which together account for almost 90% of all exports. The US imports Expeditionary Fast Transports (EPF) for its Navy that are made almost entirely by Austal’s US subsidiary. Indonesia has been known to buy second-hand C-130 Hercules transport aircrafts made by Lockheed Martin and bought new by Australia. Both examples suggest the majority of Australian arms exports are not based on local production capabilities, but rather on foreign countries’.

Looking into the future, Australian arms companies will be involved in the construction of the wings of the Royal Australian Air Force’s (RAAF) F-35A. While these are built in Australia, it remains to be seen if the companies which contribute towards the development and production of the F-35 can create significant industry spinoffs that can stimulate the creation of a competitive arms industry.

In assessing the feasibility of Australia’s export strategy, an important set of questions must be answered:

- Can foreign and local arms producers create intra-industry spillover effects that can stimulate the sector?

- What weapons should Australia produce and sell?

- Who are Australia’s main international competitors?

- Who will Australia sell to?

- How will Australia create demand for its products?

As we try to answer these questions it becomes clear that Australia is far from being able to create the intra-industry spillover effects required; faces stiff competition from various producers (including allies); does not have a diversified export base; and does not have a wide range of products that can be marketed to the international arms market.

Australia’s goal in becoming a global arms producer and exporter hardly seems feasible. By 2028 the $200 billion of tax payers’ money spent on improving defence capabilities could very well be known as an expensive experiment gone wrong.