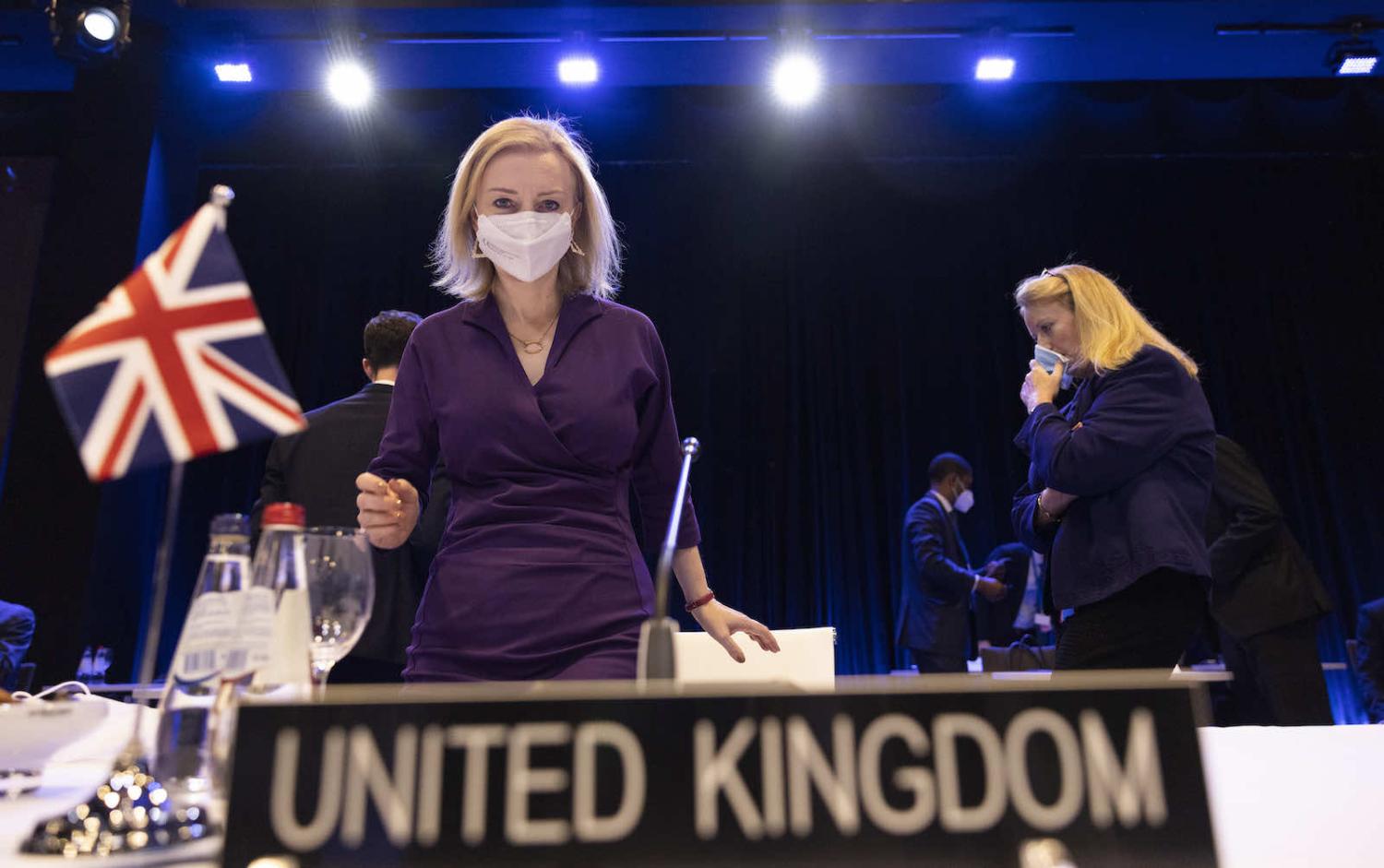

The United Kingdom became ASEAN’s newest dialogue partner in 2021 soon after launching its Indo-Pacific tilt. In the new diplomatic life after Brexit, the UK’s renewed attention to the broader two oceans, and ASEAN in particular, needed reframing. The dialogue partner status presents a chance for the UK to justify its own priorities and distinguish itself from similar Indo-Pacific ideas of the European Union.

So far, Southeast Asia has welcomed external partners, the interest from Europe and elsewhere, and a tradition of cooperation has been well established. Engaging with external actors helps escape the perception of a US-China domination of world politics.

But there is a sense of conflict between “the more the merrier” approach of welcoming, even actively engaging, external partners, and a growing concern about “over-crowdedness” in the region resulting in competition over agency and control. Overcoming this challenge will depend on the implementation and consistency of the EU and the UK’s respective Indo-Pacific strategies. While it’s still early days, such a challenge is worth bearing in mind from the outset.

The question is whether there are too many Indo-Pacific inputs right now from various European actors, individually and collectively? Is it helpful to have ASEAN-UK, ASEAN-EU, ASEAN-[fill-in-the-blank] mechanisms on the same issues? As natural as it may sound in the usual conduct of ASEAN-related diplomacy, it presents as a bureaucratically challenging exercise.

A decline of multilateralism is detrimental to what ASEAN has liked to call “habits of cooperation”.

Nor should it be assumed that Australian collaboration with the United Kingdom in the Southeast Asia region will be automatically welcomed. As the recent example of AUKUS demonstrated with mixed regional reactions as well as expression of outright concern, local political sensitivities need to be considered.

ASEAN itself also encompasses a diverse set of interests and it cannot be assumed that engaging the organisation guarantees that each will be treated equally. The system of a rotational chair for ASEAN will inevitably involve a shift in preferences and emphasis for issues, such as maritime cooperation for example, along with varying levels of eagerness to cooperate with individual external partners.

For the United Kingdom it is a natural fit to focus on maritime issues in engaging ASEAN. Given the UK’s strengths in the maritime domain here are some areas categorised into two separate streams where I see the most difference could be made, allowing that there will always be challenges about prioritisation within resource constraints:

Protecting the old and already committed to, but often violated, or dismissed elements of maritime order

- Investing in capacity training in legal expertise among the Southeast Asians for the maritime order, particularly involving legal issues. The UK, as well as Australia, have been attractive higher education destinations. This mutually beneficial interest can be further leveraged by more scholarships offered in legal, especially maritime law, studies.

- Securing a safe and protected marine commerce environment, particularly given the disturbance of the global supply chain and trade disputes. This objective also applies for offshore resources, including oil and gas. This issue requires reinforcing adherence to the international law and understanding the obligation of the parties.

- Forging a common approach in response to the grey zone tactics and provocations that seriously challenge the peaceful conduct of maritime activities. Establishing such a common approach will be difficult but without the effort the chances for sustaining maritime order are slim.

Innovating in the maritime order for new opportunities and to address renewed challenges

- Support for environmental research and protection, including areas such as fisheries, plastic pollution, climate change and disaster prediction. This can be further facilitated by technology and information sharing, creating research repositories for the development of knowledge and technologies relating to transboundary issues.

- Informing the “blue economy” – something that excites all ASEAN as a new buzzword for post-pandemic recovery. Combined with the opportunities of the digital transformation, helping the region develop common definitions and standards would be of significant benefit.

- Cooperation in capacity building in technology, cybersecurity and maritime-based digital infrastructure. Technology adoption is transformational and will define the future of maritime activities and safety in the Indo-Pacific and affect Southeast Asia’s safety, security, livelihoods and economies.

Most importantly, external partners must strive to sustain and foster an atmosphere of cooperation. A decline of multilateralism in recent years has been detrimental to what ASEAN has liked to call “habits of cooperation”. The nature of the maritime domain as a global common requires a cooperative spirit. That, self-evidently, is in everybody’s best interest.

This article is a part of a series examining regional perspectives on maritime security. This project is led by La Trobe Asia, Kings College London and Griffith Asia Institute with the support of the UK High Commission in Canberra.