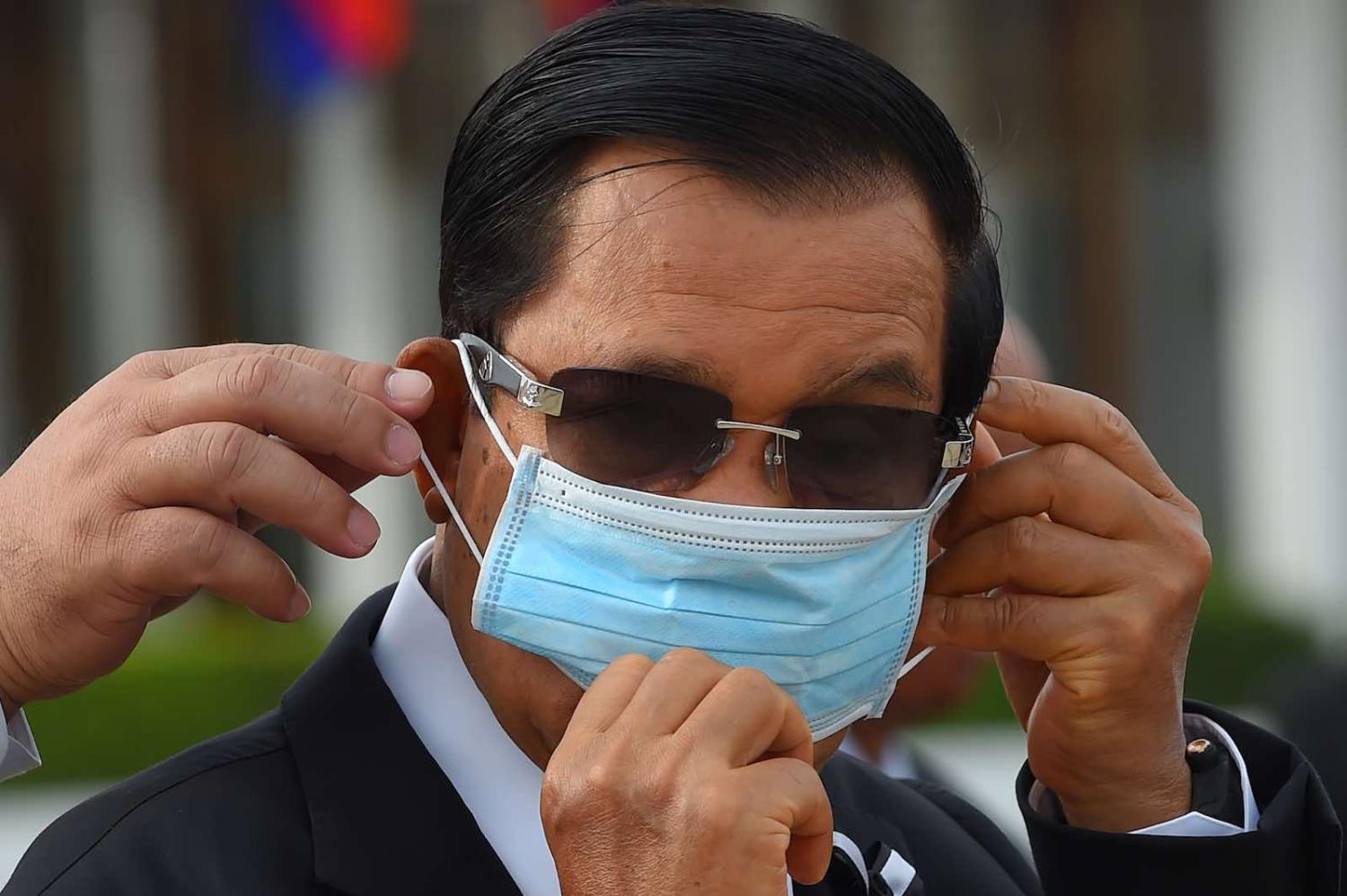

Even as it grapples with the economic fallout of Covid-19, Cambodia has a China problem. The perception of Prime Minister Hun Sen as a stooge for Beijing became entrenched long before the coronavirus outbreak – but it was left unexplained. However, as the virus is gradually brought under control, this idea of Cambodia circling ever more tightly in China’s orbit and descending into dictatorship threatens the country’s economic recovery.

The supposed China connection has been elevated since The Wall Street Journal reported in July 2019 that Cambodia was helping China realise its “string of pearls” strategy by allowing Beijing military access to a naval base in Sihanoukville. It has kept resurfacing, including with speculation that other nearby ports are under construction.

The allegations that Cambodia is likely allowing China to build dual-use ports capable of accommodating Beijing’s military aircraft and warships are not a welcome sign. Such speculations lack concrete evidence and have been vehemently denied by the Cambodian government, but they have serious repercussions for Cambodia.

They not only further undermine Cambodia's image on the regional and international stage, but they also potentially place the country in the centre of strategic competition for dominance in the Asia-Pacific between China and the US.

Tilting towards China – or just appearing to be – at the expense of US relations could spell disaster for the country and its people in the long run.

In recent years, Cambodia and the US have experienced growing mutual strategic mistrust. While the US is suspicious of Cambodia’s increasing friendliness towards China, Cambodia is wary of the US push for regime change in Phnom Penh. However, Hun Sen was assured last year in a letter from US President Trump that “the United States respects the sovereign will of Cambodian people and we do not seek regime change”.

The cost of this strategic mistrust is measurable. Despite relative success in controlling the spread of Covid-19, Cambodia needs effective post-pandemic recovery strategies and policy responses to build back better economically. The World Bank has predicted a sharp decline in Cambodia's 2020 GDP growth, potentially registering a negative growth rate of between -1 and -2.9% – the slowest growth since 1994.

The situation is dire. Cambodia’s main GDP growth drivers such as the garment, tourism and construction industries are faltering. Almost 200 garment factories in the country have suspended operations, and around 170 companies in the tourism industry have been shut down.

Cambodia will need broad international ties to support its recovery. While the pandemic is still severely impairing global supply chains, and the tourism industry still hobbled by international travel bans and other restrictions, such links will need to be re-established.

Thus, Cambodia cannot afford to be branded a China lackey. To address the strategic mistrust between Phnom Penh and Washington, the US needs to engage Cambodia in ways that are neither confrontational nor undermining towards the Kingdom. Although efforts have been made and positive developments have emerged in recent months, relations are still strained.

While Cambodia continues to conduct foreign policy guided by economic pragmatism, it needs to strike a fine balance in its relations with the superpowers. Tilting towards China – or just appearing to be – at the expense of US relations could spell disaster for the country and its people in the long run.

Engaging all partners, the US and its allies in particular, is therefore vital to Cambodia’s foreign policy and sustainable development. Its inclusive foreign policy motto, “Reforming at home and making friends abroad based on the spirit of independence,” is a great strategic vision, but realising it is not so easy.

Meanwhile, Cambodia needs to address domestic challenges such as corruption, human rights violations, social injustice and environmental issues in order to sustain bilateral aid.

One of its post-pandemic priorities will be to resolve its differences with the European Union – Cambodia’s largest export market – over concerns surrounding the partial withdrawal of the “Everything But Arms” (EBA) trade scheme Cambodia has enjoyed since 2001. Although Cambodia can still export to Europe even without the EBA scheme, the loss of trade privileges would have a negative impact on the garment industry, which accounts for over 80% of Cambodia’s exports.

Cambodia also has to recalibrate the trajectory of its political development, widely perceived as edging towards authoritarianism. Although it favours political elites, staunch government supporters and particularly Prime Minister Hun Sen (who has been in power for more than three decades), it may not reflect the interests of around 3 million Cambodians who voted for the opposition party in the commune elections in 2017.

The country’s perceived descent into authoritarianism clearly does not align with international efforts invested since the 1990s to assist Cambodia in upholding democratic values and practices. A reconsideration of the country's overall political trend and increasing repression of dissent are therefore urgently needed.

At the same time, as it works to deal with the many social and economic challenges caused by Covid-19, the country’s strategies for economic recovery need a vision that goes beyond the economic sphere.