Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has always been coated in Teflon: the kinds of policies and actions that would have brought down other leaders have barely left a dent in his impeccably tailored vests.

But as it turns out, there is a chink in his armour: farmers. Specifically, 250 million of them, many of whom continue to take part in a weeks-long protest against new laws, passed in September, that would see the agriculture sector potentially opened up to large, private companies, meaning farmers would lose out.

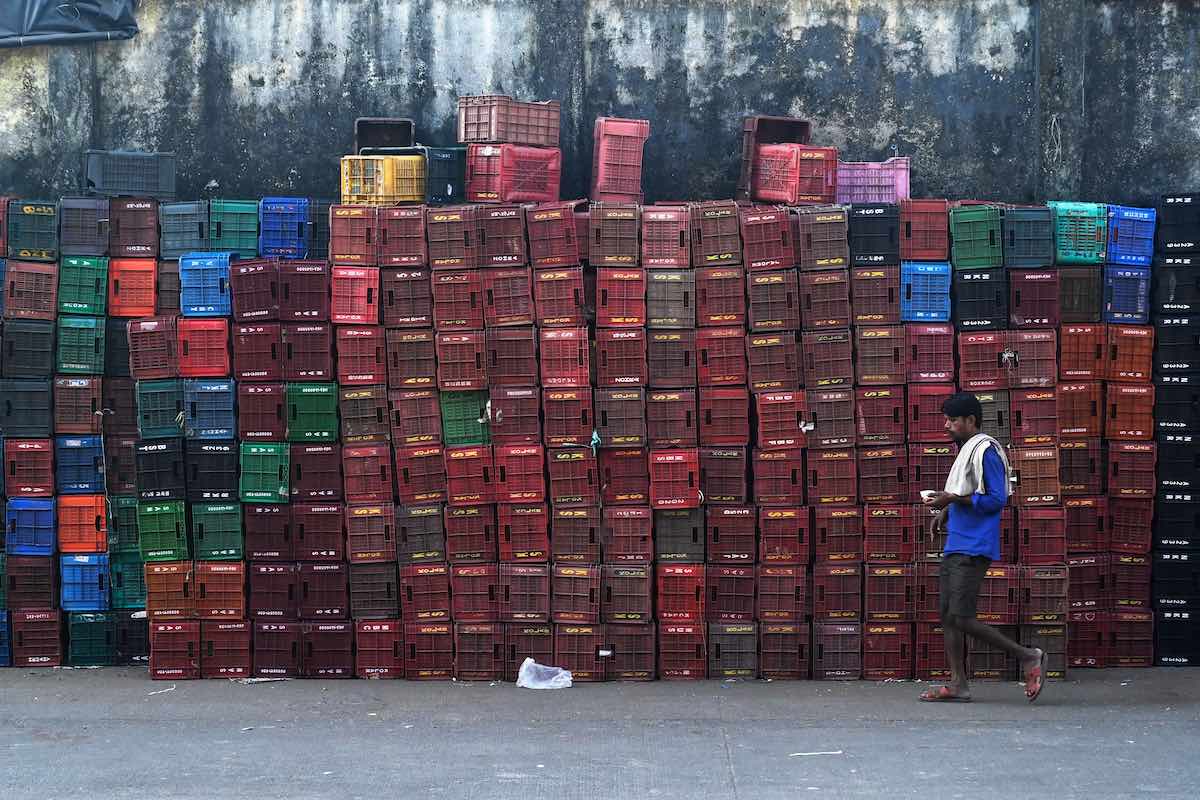

Across India, many millions of farmers are up in arms, while in New Delhi, tens of thousands of farmers from the nearby states of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana have descended on the city, some arriving on tractors, where they blocked roads and set up camps, hunkering down for a long protest.

For Modi’s armies of loud and passionate supporters, as well as his vast base of support in middle India, this is tricky terrain.

India remains largely agricultural: almost half the working population is in the sector, according to census data. Even those not working in farming tend to have strong familial links to the land.

And herein lies the rub: for civil society, to not support the farmers would be tantamount to, say, barracking for Australia in the cricket. But supporting them means tacitly taking part in what amount to anti-government protests. For Modi’s armies of loud and passionate supporters, as well as his vast base of support in middle India, this is tricky terrain.

The diaspora has also been drawn in. From Sydney to Toronto to Birmingham and beyond, protesters have gathered to add their voices to the dissent. It is a far cry from Modi’s infamous “Howdy Modi” moment in Texas, where a stadium-full of supporters turned out for him.

Modi: a man with a mandate

Modi’s 2014 election victory was so comprehensive that to this day the country does not have an official opposition party, since the Indian National Congress has failed to win the required 10% of seats in the country’s lower house of parliament. Five years after that thumping win, he more or less repeated the act at the next election last year. His emphatic electoral success has given Modi wide sway within his Bharatiya Janata Party to govern as he sees fit, and shape policy accordingly.

India has changed dramatically since 2014 – from a country excited by the economic bounties coming their way to one where religious fervour is creeping everywhere and democratic values are being stifled. One of the government’s moves has been to muzzle dissent, targeting human rights NGOs such as Amnesty International and arresting activists.

Modi’s success has also allowed him to weather political storms that would have subsumed other leaders. There are not many who could survive cancelling their country’s legal tender overnight and reissuing new notes without warning, which he did in 2016, throwing the entire country into chaos. Even India’s handling of coronavirus, which has seen almost 10 million cases and close to 145,000 deaths, hasn’t seemed to have had much of an impact on the government’s approval ratings.

And as with populist movements the world over, Modi has amassed a huge army of vociferous supporters who are swift to condemn critics of the government as un-Indian, or worse.

But now the BJP administration might have finally hit a snag in its quest to reform the agriculture sector. For Modi, a man more used to adoring crowds, the scale of the protests – and the demographics of them – is something likely to come as a shock.

And that is exactly what makes these protests so noteworthy: apart from the sight of thousands of mostly Punjabi farmers suddenly thronging the streets of the capital, it is arguably the first time that India’s civil society, en masse, has essentially stood in opposition to the Modi government. Those who couldn’t care less about the issues promoted by Amnesty International, nor the fate of the organisation’s Indian presence, now find themselves on the side of the dissenters, which is a strange place for them to be.

The protests and the elections

This could well mark an inflection point in Modi’s premiership. The next federal election is not due until 2024, buying Modi some time to literally calm the farm before his government faces re-election. Between now and then, however, a number of states will go to the polls, including Kerala, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal in the first half of 2021.

While none are particular strongholds for Modi’s right-wing BJP, the widespread dissent surrounding the farming laws is unlikely to do the party any favours. And should the farm remain restless beyond 2021, early 2022 will see elections in Goa, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, where the BJP enjoys more electoral success but could be vulnerable to a backlash.

Whatever the rights or wrongs of the farming legislation – and there are arguments on both sides of that coin – the issue has been the hard-headed manner in which they were driven though parliament with minimal consultation. To date that “crash or crash through” approach has served Modi well, and the lack of opposition has likely emboldened a belief that he can dispense with the coalition-building that successful reforms typically rely upon.

Now however, in farms and cities across India, and around the world, a coalition is building itself in opposition to Modi and his tactics. Where that coalition goes will be one of the defining elements of Indian politics.