Climate change is one of the world’s most pressing challenges, and one which impacts humanity as a whole. A recent United Nations study indicates that decreasing biodiversity in our food supply is augmenting the peril posed by climate change and a growing population: nearly a quarter of wild food species are in decline according to the report.

Along with Latin America and Africa, the region of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, is one whose food supplies are set to be hardest hit by climate change. Indeed, serious problems have already surfaced. The Philippines are suffering from a massive water shortage due to a severe drop in dam levels, leading to the surreal sight of lines of pail-carrying Manila Water customers waiting to fill at pumps and chasing firetrucks.

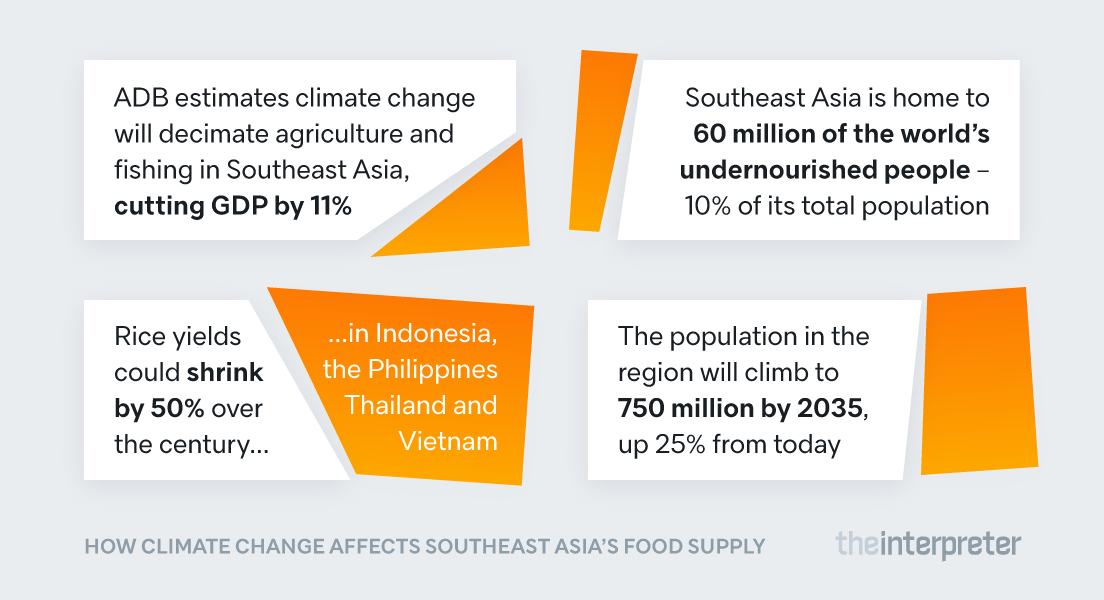

Furthermore, fisheries – a vital source of food for more than half the world’s population – have been significantly impacted by rising sea levels. Southeast Asia with its lengthy coastlines, massive archipelagos and rich river deltas is one of the most severely affected regions. Although the region has experienced rapid development, it is still home to 60 million of the most undernourished people in the world – not surprising given that Asia has more than half the world’s population and yet only 20% of the globe’s agricultural land.

With Southeast Asia’s current population of 600 million expected to climb up to 750 million by 2035, it is clear what devastation could be wrought by rising sea levels, rising average temperatures and increasingly extreme weather patterns. Rice, the most common staple in the region, is particularly vulnerable to these changes. The Asian Development Bank estimates that Southeast Asia’s GDP could be cut by 11% as industries such as agriculture and fishing are decimated by climate change.

Barring significant technological breakthroughs, rice yields in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam could sink by as much as 50% over the course of the 21st century. Critical low-lying delta regions, host to many of the region’s most productive agricultural basins, could all be wiped out. Glaciers on the Tibetan plateau, which feed crucial rivers from the Mekong to the Irrawaddy, are melting. Yields of other staple crops such as wheat and maize have also plateaued in recent decades, making food security amidst a rapidly growing population base a major priority.

Investing in technology to combat the challenge

However, it’s not like ASEAN members are standing idly by as the problems accumulate. On the contrary, several programs exist to alleviate climate-related concerns using high technology and the fourth industrial revolution.

In Singapore, a new 18 hectare agri-food innovation park is taking shape, which the government hopes will become a catalyst for developing a hub of industries in the field of sustainable agro-technology. Pioneering companies are growing multi-level farms on rooftops in an attempt to develop high yield agricultural systems in dense urban areas.

These innovations are in line with the government’s goal of producing 30% of the city state’s nutritional needs by 2030, up from a paltry 10% today. In order to achieve this target, new technologies are focused on dramatically enhancing yields, building climate-resistant growing systems and developing sustainable environmental production – all while using drastically less land, water and resources than current practices. What Singapore’s agricultural industry lacks in space, it makes up for in its access to a highly educated work force, research and development capacity, and immense government support.

Region-wide initiatives

Other ASEAN countries are following Singapore’s lead. Adaptation techniques have been widely adopted in the region, including changes in crop patterns and diversification into less water-intensive crops such as cereals, pulses and millets.

Southeast Asian governments have recognised that one way to mitigate the threat to food security lies in leveraging cutting-edge technologies.

Various initiatives including the ASEAN Cooperation on Agricultural and Bio-systems Engineering (ACABE) and the ASEAN Universities Consortium on Food and Agro-based engineering and technology education (AUCFA) are working to develop a region-wide platform for knowledge and technology sharing for harnessing the power of the fourth industrial revolution – one which is hoped to solve common problems for the region’s agricultural industry. In the run up to the 22nd session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 22) in Marrakech, ANGA (ASEAN Negotiators Group on Agriculture) prepared a joint submission calling for a list of priorities including scaling up finance, improving access to technology, taking more accurate measurements of progress and augmenting regional cooperation.

The hope is that advancement in high-tech fields including GPS, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and connectivity can produce higher yields and stabilise food supply during a period of climate uncertainty.

In Indonesia, companies such as i-Grow have come up with a solution for planting under-utilised land by getting individuals to invest remotely in seeds. A one-time investment of roughly $1200 in peanut seeds, for example, could potentially yield a return of 9-13% in six months.

Other companies, such as Indonesia-based CI Agriculture, aim to use technology to slash loan costs for small-holding farmers by using satellite, drone and sensor data to more accurately calculate a field’s production potential. This same data can also be used to apply fertilizer and pesticides more efficiently, using fewer chemicals to achieve the same yields.

These initiatives show that Southeast Asian governments have recognised that one way to mitigate the threat to food security lies in leveraging cutting-edge technologies. In working to make use of the fourth industrial revolution, the region could become a beacon for the rest of the developing world.

Many developing countries in South Asia, Africa and Latin America share similar climates, latitudes and economies with Southeast Asia. ASEAN – with its population density, geography and industrialisation – is both one of the most climate-vulnerable regions and a place where innovation can potentially be fostered to meet these challenges. ASEAN’s experience could ultimately become a crucial foundation for other states in the developing world and humanity as a whole.