In recent years, China’s digital economy has seemed like a house undergoing full-scale renovation. At this moment, it appears to be in the demolition stage.

In a series of regulatory smackdowns, the magnitude ranging from sledgehammers to wrecking balls, Beijing has appeared willing to lay waste to entire industries and billion-dollar firms in the interest of rebuilding much of the country’s technology and internet sectors to align with its objectives.

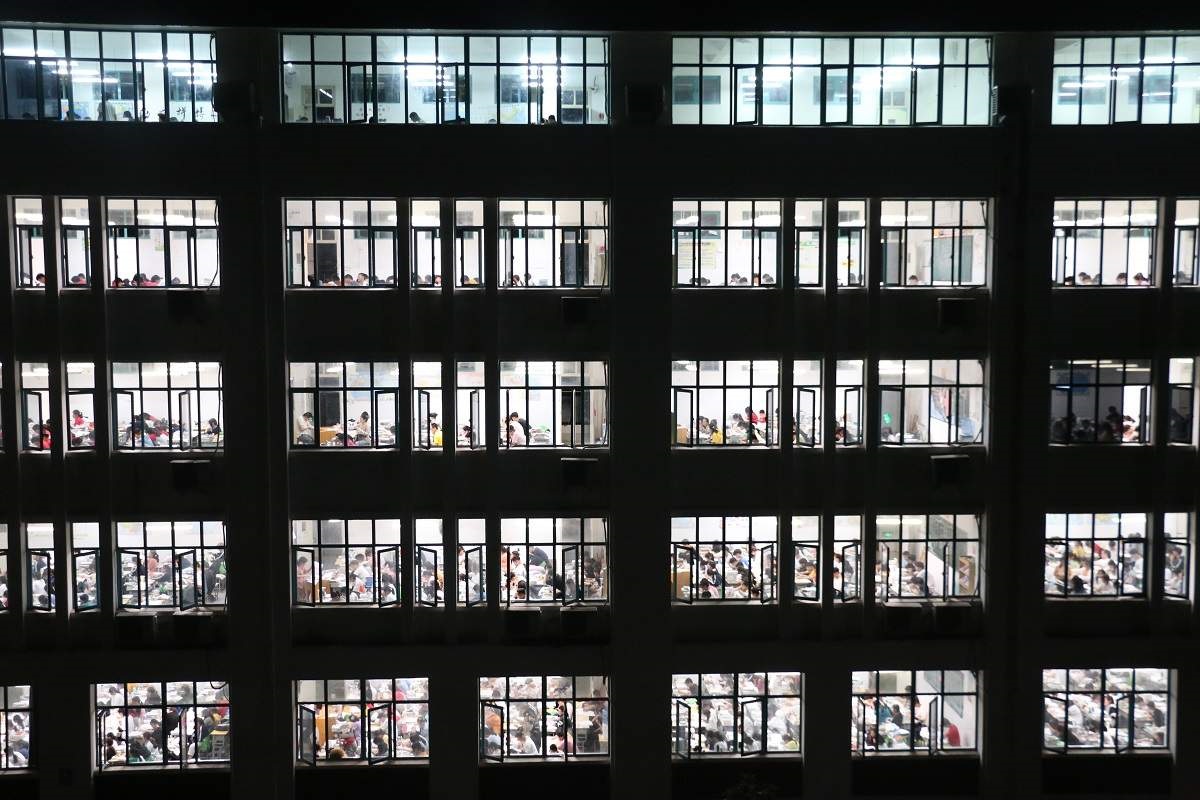

Thus far, casualties have included Ant Group, whose planned initial public offering (IPO) in November 2020 was set to be the largest in history until authorities slammed the brakes and imposed rules forcing the fintech giant to restructure much of its business. After the ride-hailing company DiDi Global reportedly ignored warnings not to go through with its June public offering in the United States, Beijing responded swiftly with a thorough probe of the firm’s data security practices, ordering the removal of DiDi apps and mini-programs by the country’s major internet platforms. Yet, Ant and DiDi seem to be enjoying far more favourable circumstances than China’s private and online education providers, who now face what appears to be a virtual ban on their entire industry. As speculation intensifies as to which sector may be next, investors in healthcare to real estate to gaming are all spooked.

The demolition and potential reconstruction of China’s digital economy is being undertaken through various bureaucratic entities within the apparatus of the state.

Who is doing the demolition, and what do they want to rebuild?

Authorities in Beijing look to be unleashing an all-out barrage on the country’s largest digital and private-sector players. And the current manoeuvres are not without method. The demolition and potential reconstruction of China’s digital economy is being undertaken through various bureaucratic entities within the apparatus of the state, yet the interests of those entities are known to both align and conflict with one another.

Consequentially, there is now a rapidly expanding list of state regulatory agencies that find themselves with expanding budgets, scale and power to accomplish their aims. Some of the most prominent include:

- Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC)

Founded in 2011, China’s internet watchdog has largely served the role of policing the country’s heavily censored online content. However, as the internet has grown in prominence, so has the CAC. With what appears to be an expanding mandate in overseeing data and network security, the CAC’s role in DiDi’s IPO debacle may have set a new precedent, ensuring that any of the country’s tech firms hoping to go public can only do so with the CAC’s approval.

According to industry observers, the CAC’s data crackdown is part of a long-term process of establishing a secure quasi-public infrastructure system for controlling China’s data that limits monopolistic behaviour by tech giants, making room for innovation and competitive disruption.

- State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR)

As China’s top market regulator, SAMR has demonstrated its ability to wield wide-ranging authority over the country’s private sector through an expansive interpretation of anti-trust law. Founded in 2018 through the merger of three existing agencies, Beijing’s new super-regulator is perhaps most famous for fining online commerce company Alibaba US$2.8 billion for its anti-competitive “forced exclusivity” practices and for blocking the merger of Huya and DouYu, two US-listed gaming platforms.

- People’s Bank of China (PBoC)

For much of the last decade, China experienced a historic flowering of its fintech industry. As Alibaba and Tencent’s online platforms facilitated cashless transactions and digital lending with ease, the country’s startup ecosystem boomed with seemingly countless ventures in areas such as peer-to-peer lending and blockchain technology.

Yet as such explosive growth often circumvented China’s notoriously sluggish state banks, it posed a challenge to the PBoC’s control over the country’s financial and monetary systems. Partly spurred on by a series of scandals in the later years of China’s fintech bubble, the PBoC has spent much of the past few years regaining control over the economy from the tech sector. Its highly-publicised investigation of Ant Group following the firm’s cancelled IPO is one of a number of recent actions that send a clear signal about who in fact is the master of the RMB.

More regulators getting in on the action

Though much of Beijing’s beefed-up regulatory enforcement has been targeted at the tech sector, emphasising data security, anti-trust and fintech, there are signs that this may be merely the beginning of widespread regulatory scrutiny and restructuring across the private sector and economy as a whole.

President Xi Jinping appears to be envisioning a stage in China’s development that some observers have compared to America’s progressive era under Theodore Roosevelt: a period of wealth redistribution to correct the excesses of a “gilded age”. In a highly-publicised 17 August meeting, Xi spoke of a need to restrain “unreasonable income”, hike wages and grow the middle class, signalling that an expanded taxation regime and further curbs on corporate power (and expansion of regulatory power) are likely to come.

“Wolf Warrior” diplomacy has wiped out much of the goodwill that China had built over decades among the international community.

The long-term stated objectives of Xi and his regulatory forces are ambitious and admirable. However, as in the case of any home renovation, to demolish requires a very different set of skills and tools than to rebuild. For the near-decade he has spent in charge, Xi has used the tools of state power to demolish many of the components of China’s reform and opening-up policy.

The vibrant yet chaotic economic environment that prioritised growth has become a casualty of Xi’s anti-corruption campaigns, replacing a culture of greed with one of fear. The flexible approach that allowed Hong Kong to be one of the most socially and economically dynamic regions on the planet is now a thing of the past, initiating an era of brutal repression on one of the world’s great cosmopolitan cities. “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy has wiped out much of the goodwill that China had built over decades among the international community.

There have been numerous leaders throughout history who have taken power over flawed systems and torn down their institutions with the promise of building something better in their place. What many have found is that it is much more difficult to rebuild functional systems than it is to control or demolish those which already exist, and that the regulatory organs of an authoritarian state are far better suited to the latter.

It appears, from evidence including the recent crackdown on China’s tech and education firms, that Xi Jinping is more than willing to lay waste to the institutions and dynamics that have powered the country’s success. We have yet to see if he can rebuild them, or if he is just killing the golden geese of China’s economic miracle.