Last year Papua New Guinea’s High Commissioner to Australia, H. E. Charles Lepani — who was one of the first Papua New Guinean heads of a government department at independence — observed in Reflections: 39 years of Sovereign Statehood in Papua New Guinea that, despite the two countries’ closeness and successive leaders ‘tireless efforts … to build our relations',

Australia remains substantially ignorant of Papua New Guinea. You cannot dig any deeper than the ongoing Manus issue to see the vitriol and vilification borne out of ignorance by Australians of Papua New Guineans and our country.

As Sean Dorney makes clear in The Embarrassed Colonialist, the situation remains much the same a year later: Australians are mostly ignorant and indifferent in regard to Papua New Guinea.

When Don Aitkin and I analysed Australian public opinion polls from the mid-1940s to the lead-up to Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975, our conclusion was remarkably similar. As we wrote in Australian Outlook at the time: 'During the last thirty years, the Australian public has had little knowledge of the New Guinea area, and cared little about it'.

Studies of British and Dutch public opinion concerning their countries’ colonies, including Dutch New Guinea, reached much the same conclusions.

Some 40 years after Papua New Guinea became independent, the 2015 Lowy Institute Poll suggested that Australians are beginning to adopt increasingly positive attitudes to the need to address global warming, an issue of particular concern to Papua New Guinea, though support for Australia’s foreign aid programme remains weak. The overwhelming majority of Australians believed that stability in Papua New Guinea is important to Australia (82%), and that Australia has a moral obligation to our former colony (77%).

Public support for Australian aid and for Papua New Guinea’s economic prospects was much weaker. And, while just under a quarter of Australians surveyed admired Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, just over 60% did not even know who he was. However, as fewer still could identify India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, these figures might suggest less about Australians’ interest in PNG than their awareness of other countries more generally. The feelings barometer, which is intended to measure Australians’ over-all feelings towards 18 other countries, ranks PNG at number 8, quite some distance below Fiji and roughly equal with China and Malaysia.

In the case of the Manus Island detention centre, sending, processing and resettling asylum-seekers in Papua New Guinea is widely depicted as a strong disincentive to people from other countries trying to make their way to Australia without proper documentation

When it comes to the question of Australia’s colonialist embarrassment, Gough Whitlam was, surely, concerned with the likely diplomatic and wider international embarrassment of continuing Australian rule when he expressed support for an early transition to independence for Papua New Guinea at a time (in the late 1960s and early 1970s) when formal decolonisation was becoming a global norm.

According to the Australian Government-sponsored history of Australia’s role in Papua New Guinea from 1945 until independence, a few former senior officials who returned there for the independence ceremonies in 1975 were embarrassed by the colonial style of the arrangements, the VIP enclosures, the evidence of privilege, and the unfamiliar gulf between officials and the people.

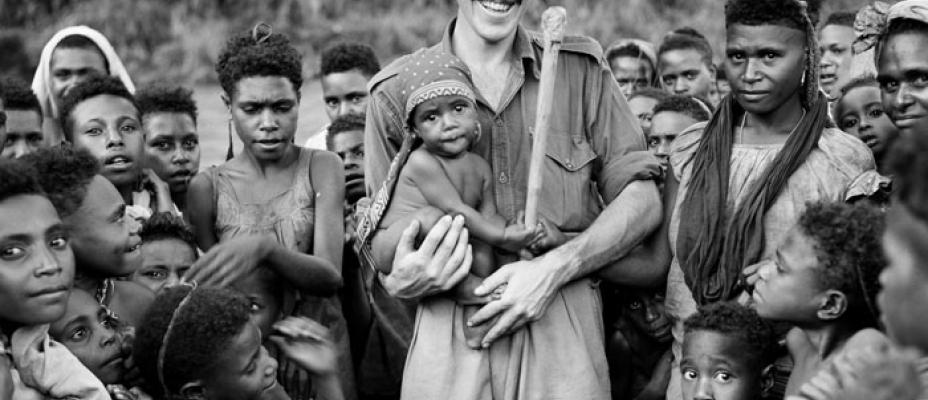

However, the Australian former kiaps who pressed for a medal in recognition of their efforts in Papua New Guinea were clearly not embarrassed by a past in which they had played such a pivotal role (they were eventually made eligible for the Australian Police Overseas Service Medal in 2013).

A noteworthy feature — really a gap — in Australia’s colonial legacy is the relative lack of a Papua New Guinean presence in Australia. According to the 2011 national census, there were then only some 26,787 persons born in PNG known to be living here (though there are likely to be others who have crossed the border without being officially registered or who, having entered lawfully, have overstayed). Of the Australian residents shown as Papua New Guinea-born, only some 8,752 were recorded as being of Papua New Guinean ancestry (the two next largest groups were of Australian and then English ancestry). Compare that with the obvious presence — and impact on cuisine and other aspects of culture — of people of indigenous descent from former colonies resident in other former colonising countries.

While a number of Australian artists and writers have drawn on Papua New Guinea in paintings, films, poems and books, both non-fiction and fiction, what impact has PNG really had on Australia? [fold]

Papua New Guinea is home to a rich array of staple foods — sweet potato, taro, cooking bananas, yams, cassava, sago, various greens, and other vegetables —and diverse ways of preparing them. But where is there a restaurant serving any form of Papua New Guinean food anywhere in Australia? Or even a readily accessible cookery book? While there is now a café serving Papua New Guinean coffee in Sydney, how easy is it to find and then buy even the small range of products — coffee, chocolate, and organic virgin coconut oil — sometimes available in some Australian stores? Compare this with the impact that other former colonies, particularly in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, have had on the cultures, including the cuisines, of former colonising countries in Europe and North America (and, dare one add, Australia).

Thus does the ongoing legacy of the White Australia policy (which applied even to Papuans, who were formally Australian citizens but without right of entry to Australia) continue to haunt relations between Australia and Papua New Guinea.

Both countries have been fortunate in the professionalism, commitment to observe, determination to understand, and willingness to do more than just report events of some of the Australian journalists who have written about PNG. Those who have written books about Papua New Guinea include both Australian-based visitors such as Gavin Souter, Osmar White, Keith Willey and Peter Hastings, as well as residents in Papua New Guinea such as Don Woolford and Don Hogg. Sean Dorney is apparently unique in being a member of both groups at different stages in his career.

The number of journalists now reporting on PNG for an Australian audience has reached a new low (only one, employed by the ABC). This means that stories emanating from Papua New Guinea are less diverse, both in coverage and viewpoint, than previously. It also means that many events worthy of being reported are less readily accessible than before as there is no longer a group of otherwise competing journalists able to share the costs involved in chartering an aircraft or boat in order to access places where interesting stories await.

Australian-based media — television, short-wave radio, and certain newspapers — are readily accessible in, at least, some places in Papua New Guinea. Rugby League State of Origin matches seem to attract even greater public interest in PNG than they do at home. Might there not be a strong case — quite apart from advocating an enhanced Australian journalistic presence in Papua New Guinea — for media organisations, even governments and non-government organisations in both countries, to work together to establish a Papua New Guinean journalistic presence in Australia? This could both provide audiences in Papua New Guinea with stories and supply a Papua New Guinean perspective on Australian news. Both would enhance a mutual understanding.

Photo courtesy of National Archives of Australia

This ‘tribe’ constitutes a significant Australian constituency for PNG. It includes the thousands of Australians engaging with the country today; those working on resource projects and in commerce, NGO professionals and volunteers, and others who keep returning for one more project, one more posting. Many visit to try to appreciate their forebears' wartime experience of the country.

This ‘tribe’ constitutes a significant Australian constituency for PNG. It includes the thousands of Australians engaging with the country today; those working on resource projects and in commerce, NGO professionals and volunteers, and others who keep returning for one more project, one more posting. Many visit to try to appreciate their forebears' wartime experience of the country.