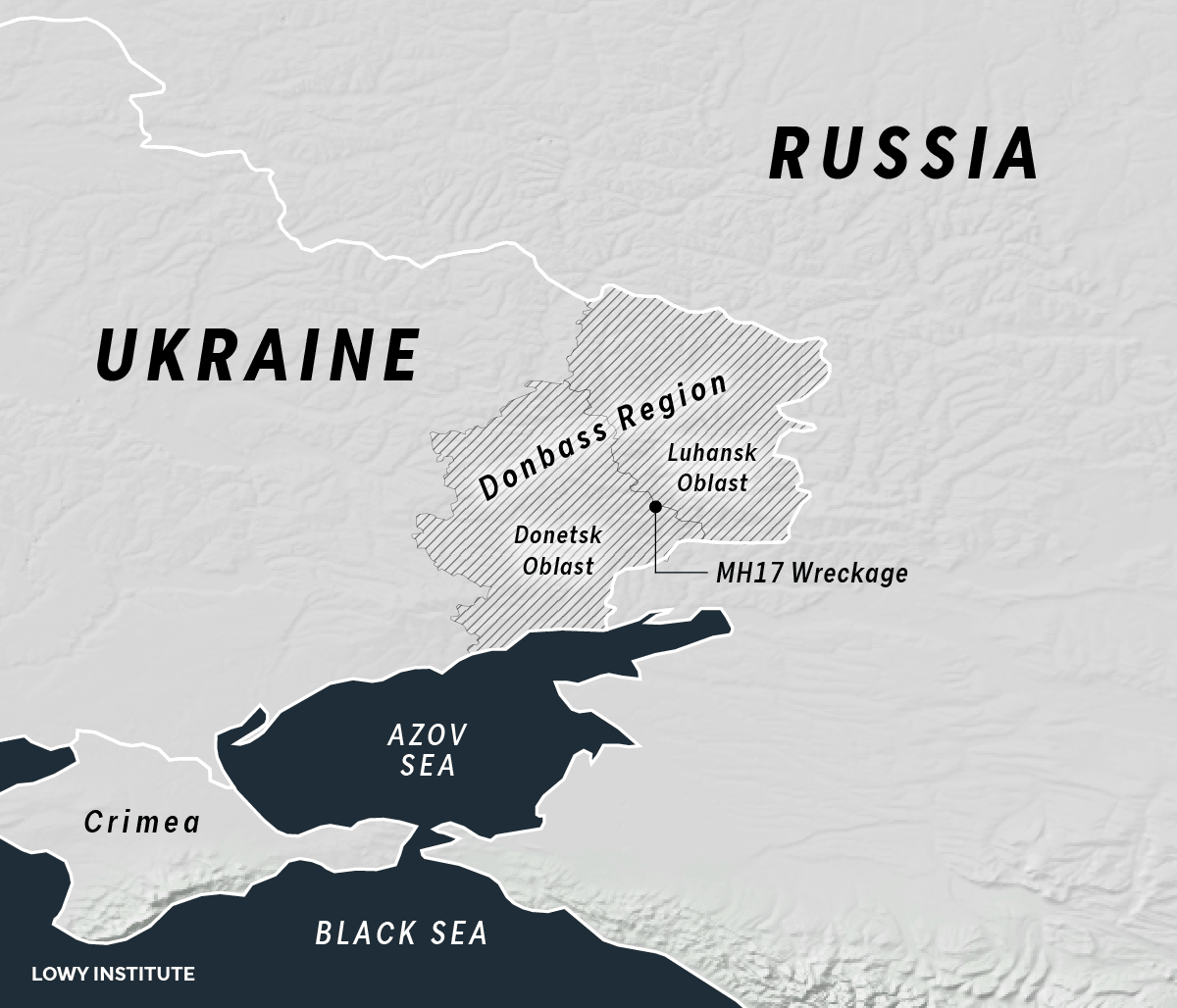

Europe’s “forgotten war” between the Western-backed Ukraine and the Russian-sponsored, self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic and Lugansk People’s Republic over the energy-rich Donbass region of eastern Ukraine has been “on hold” for six years. Despite the formal truce declared in 2015, shelling and sporadic firing have been an everyday reality for the local population, and there are indications that both Kiev and Moscow are preparing for a potential escalation of the conflict that erupted in 2013.

Ukraine is actively modernising its military. According to reports, the Eastern European country is set to purchase five Turkish-made Bayraktar Tactical Block 2 (TB2) unmanned aerial vehicles this year, while in 2019, Kiev tested and purchased 12 Bayraktar drones, which proved to be a game changer in recent Azerbaijan-Armenia war over Nagorno-Karabakh. Also, in 2017 the Trump administration approved military aid to Ukraine, selling 210 Javelin anti-tank missiles and 37 launchers to the former Soviet republic. The US is also expected to soon provide further lethal weapons to Ukraine, another possible sign of preparation for the resumption of hostilities in the region.

Moscow insists that Ukraine should negotiate directly with the Donbass republics, which is something that Kiev resolutely opposes.

The Kremlin, on the other hand, has sharpened its rhetoric regarding the future of the Donbass. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov declared last month that Russia has no plans to absorb the Donbass, and that Moscow is solely focused on protecting Russians and the Russian-speaking population of the region. He also noted that the Donbass has “always been Russian-speaking” and that Moscow intends to stand up for its residents. On the other hand, several other Ukrainian regions in the east and south of the country are also Russian-speaking, but the Kremlin never stood up for their residents as actively as in the Donbass. Given that energy plays a crucial role in Russia’s politics, it is not surprising that Moscow is interested in preserving its de facto control over the coal-rich Donbass basin.

Other voices are more direct. “People from Donbass want to be part of our great homeland. Russia, mother, take the Donbass home,” said Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of Russia’s state television RT on 28 January in Donetsk, where she took part in the “Russian Donbass” Forum. At the summit, leaders of the self-proclaimed Donbass republics reportedly adopted a doctrine of “Russian Donbass”. The main goal of the document is said to be to “strengthen the statehood of the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics as Russian-nation states”.

That, however, does not mean that Russia will incorporate the region into the Russian Federation the same way it absorbed Crimea in 2014.

For various reasons, “the Crimean scenario” in the Donbass was not implemented. Instead, the Kremlin created two unrecognised proxy states that are heavily dependent on Russia economically, politically and militarily. Igor Strelkov, Russian military veteran and an ex-KGB officer, who is also a former defence minister of the Donetsk People’s Republic, repeated on several occasions that it was Moscow that formed army corps of the Donbass proxy states. Yet he still refuses to talk about the downing of the Malaysian Airlines flight MH17, even though he was charged, along with two Russians and one Ukrainian. Strelkov, a critic of the Kremlin, has been claiming for years that a large-scale war between Russia and Ukraine is “imminent”.

It is worth noting that before the Russo-Georgian War in 2008, the Kremlin’s policy towards Georgia’s breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia was eerily similar to Russian actions in the Donbass, where 441,000 residents already have Russian passports. Georgia’s attack on South Ossetia in August 2008 led to Russian military intervention and also to the recognition of these entities (which for a time extended to the Pacific). Unless Ukraine, backed by the West, starts a military offensive against Russia’s proxies in the Donbass, it is not likely that Moscow will recognise the Donetsk People’s Republic and Lugansk People’s Republic, although they will be closely integrated with Russia as unrecognised subjects.

In the meantime, both Moscow and Kiev will likely keep simulating the implementation of the so-called Minsk II accord signed in Belarus in February 2015 by Russian, Ukrainian and European officials, as well as representatives of the self-proclaimed Donbass republics. The first Minsk protocol (Minsk-1) was signed in September 2014. According to both documents, an immediate and comprehensive ceasefire has to be established, and all foreign armed formations and military equipment, as well as mercenaries, should be withdrawn. Besides that, Ukraine has to reinstate full control of its state border with Russia. None of these points has been implemented to this day.

Russia insists that Ukraine should negotiate directly with the Donbass republics, which is something that Kiev resolutely opposes, since it is aware that that would mean the de facto recognition of those entities. Given that the Unites States, as Ukraine’s main backer, is not officially involved in the peace talks, the chance of a sustained peace in the Donbass is very slim. Thus, the future of the region will likely be determined as part of a wider deal between Moscow and Washington.