Worker vs worker vs student

Almost five million Kiwis have always been at least cousins. And Scott Morrison’s distinctive contribution to regional security has been his embrace of about 10 million other islanders as “our Pacific family”.

But in a week of rhetoric about international relationships from the G7 to British lamb buyers, agriculture minister David Littleproud’s description of 600 million Southeast Asians as Australia’s “ASEAN family” is really something else.

Littleproud used the term throughout his media appearances on Wednesday celebrating the way existing Pacific worker recruitment has suddenly been extended to Southeast Asia in a political fix to win the British trade deal. As he put it on ABC radio:

One of the concessions that the Prime Minister was able to negotiate with myself and [Deputy PM] Michael McCormack, was that we were to have an agricultural visa that would be extended to our ASEAN family to be able to give them the opportunity to come and fill that [rural labour] void.

Claiming a big win for the Nationals – the junior partners in the ruling Coalition government – when farmers might be wary about waiting 15 years to get full access to British meat buyers while immediately losing access to them as cheap workers is understandable.

Extending the usual trade deal hyperbole to calling such diverse countries “family” only runs the risk of adding to Australia’s perceived reputation for running hot-and-cold on these close neighbours.

But the hastily proposed ASEAN visa appears set to be less regulated than the existing two Pacific worker visas, which means it could well undermine the very schemes which are at the heart of helping the original Pacific family. Having even more different visa arrangement under which visitors can work in rural areas is hardly going to make the system easier to manage or expand to other sectors, as the government is now considering (see below).

Depending on how it is managed, recruiting Southeast Asian workers into agriculture might make a useful addition to Australia’s recent increased focus on these countries in response to China’s assertiveness.

But extending the usual trade deal hyperbole to calling such diverse countries “family” only runs the risk of adding to Australia’s perceived reputation for running hot-and-cold on these close neighbours. These countries would no doubt welcome perhaps 10,000 of their workers getting jobs and training in Australia. But their ambassadors have been asking questions of the government for a year about the future of many more of their citizens whose education in Australia has been disrupted by pandemic lock downs.

And those students will likely be much more important to longer term bilateral economic and security relations than seasonal farm workers.

Back to the future

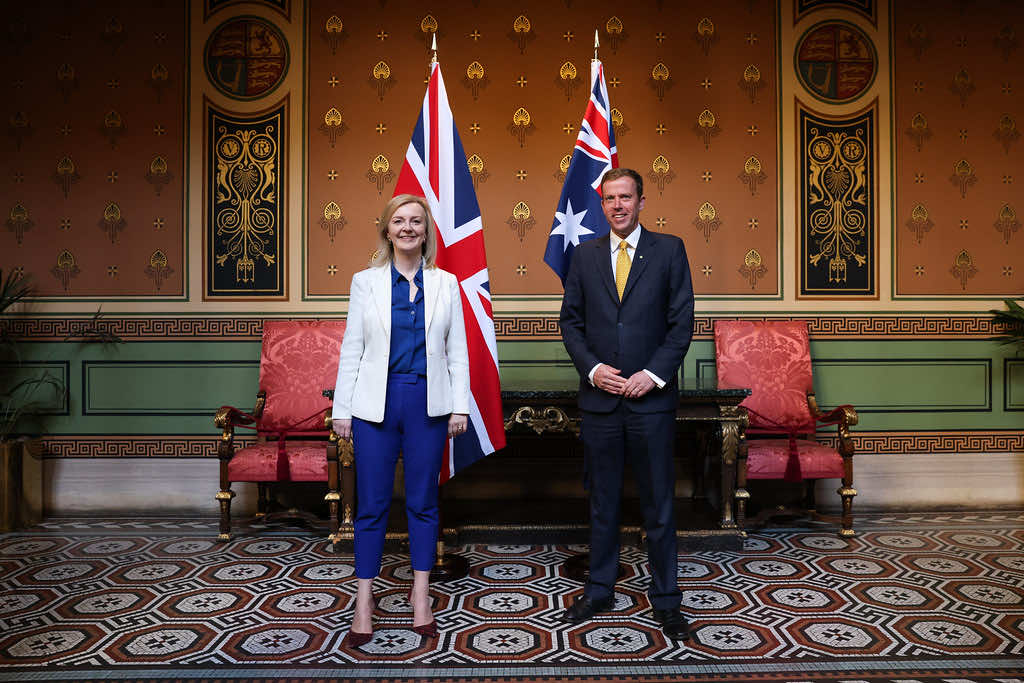

While the Agriculture Minister has perhaps appropriately been growing the family, Trade Minister Dan Tehan sounds more like he has been in relationship counselling fixing old parental grievances.

Tehan says the British trade deal “rights an historic wrong of 50 years ago where the UK turned to Europe and left, especially Australian farmers, standing, looking for other markets.”

While the agreement is more important to Britain as it recovers from the Brexit turmoil, unlike Australia it has at least had the honesty to publish figures showing how little it will replace lost European access. It is forecast to increase GDP over 15 years by only up to 0.02 per cent, or £500 million.

Nevertheless, it sets the benchmark for what Britain will trade off in likely tougher negotiations with the US and others under a new independent trade policy. So, it is interesting to see it has triggered the same debate that has occurred in Australia which sees elements of the left and right calling for more information on trade deal negotiations to make them more palatable to the voters.

For example, the Financial Times argues in an editorial:

Negotiations require a country to present a united front and speak with one voice. Yet parliamentary buy-in as well as improved transparency and wider political support are vital to see deals over the line.

Despite Tehan’s lachrymatory, the British economic connection has overall stayed quite strong through the decades of European Union imposed separation. It remains Australia’s seventh largest trading partner, although that is strikingly dependent on Australian gold exports.

And while all the attention has been focussed on trade this year, investment has been the real sustained economic sinew with overall British investment rising steadily in recent years and growing faster than US investment. It is much the same story going the other way, with Australian investment into Britain rising faster over the past five years than into the US.

While some government ministers have overlooked New Zealand in their zeal to claim the mantle for this agreement as Australia’s best trade deal, this is probably as good a deal as could be expected in the current global trading environment.

The big issue will be whether all the celebration about righting Tehan’s historic wrong will distract Australian business from the longer-term challenge of locking themselves into the still much higher growth in Asia than Britain.

Helping hands

It is no surprise that Littleproud resorted to “family” ties to sell the ASEAN work visa when the term is now official government language judging by the new Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade discussion paper on an expansion of both the Seasonal Workers Program and the Pacific Labour Scheme. It says:

Pacific labour mobility fosters links between people, businesses, and communities, creating deeper connections between Australia and our Pacific family.

These short-term labour arrangements and their associated training have really become the sweet spot in the Pacific Step-up as Australia has tried to make its aid go further in the regional battle for hearts and minds in the Pacific with China by using non-cash initiatives.

The value of a less regulated ASEAN visa will need to come under scrutiny.

That is because they both support conservative aid-sceptic Australian rural communities with labour and channel cash remittances back into the Pacific communities that might have lost grassroots aid in the battle to outbid Chinese infrastructure building. And the formalised people movement in and out of Australia might well lay the groundwork for more significant migration caused by climate change.

But these schemes are not without their sensitivity as was demonstrated by the Australian Workers Union secretary Daniel Walton’s response to the new ASEAN visa:

Scott Morrison and Boris Johnson have decided it's wrong for Brits to be exposed to exploitation and abuse on Australian farms, but apparently it’s okay for Southeast Asians.

The DFAT discussion paper is remarkably frank about the potential for expanding these still relatively new schemes into other industries with labour shortages in effect expanding the sweet spot for Australian business and the Pacific (and now potentially Southeast Asian) workers. It says:

The projected shortage of workers in the aged care sector is predicted to reach 180,000 by 2050, while the National Disability Insurance Scheme has estimated that up to 90,000 new full-time positions will need to be created.

The big challenge here will be the quality and flexibility of the training so that these short-term workers will be able to move with shifting demand in Australia and be skilled up in ways that are useful back home where they are ultimately supposed to return. And that is where the value of a less regulated ASEAN visa will need to come under scrutiny.

Another piece of the labour movement jigsaw puzzle fell into place this month with the Commonwealth Bank cutting the cost of remittance payments to five South Pacific countries in one of the few supportive moves by Australian banks in this part of the world since they sold off their longstanding operations on the cusp of the Pacific Step-up.

This is all certainly extending the boundaries of development aid but will require some good management to prevent a brain drain of skills away from small countries which will struggle to recover quickly from the pandemic.