The decision by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations not to invite Myanmar’s military leader to two related summits in Brunei on 26–28 October raises an intriguing question: if pushed far enough, would the junta in Naypyidaw take Myanmar out of the regional grouping?

Myanmar’s military rulers thought long and hard before joining ASEAN in 1997. To do so was seen as a break with the country’s long-held and deeply-felt attachment to independence and strict neutrality in foreign affairs. ASEAN was not allied with any major power bloc, and undertook not to interfere in its members’ internal affairs, but even so membership would compromise Myanmar’s traditional stance.

At the time, a conservative faction of the ruling military council claimed that ASEAN membership offered nothing of significant value, and would expose Myanmar to foreign pressures. However, a more progressive faction successfully argued that ASEAN could provide a buffer between the regime and its foreign critics. It would also help Myanmar to balance its problematical relationship with China.

Myanmar’s military mindset has always been difficult to understand, but the generals have always held firmly to the principle that the country must remain independent.

For its part, ASEAN was under pressure from its US and European dialogue partners not to expand, but it felt that Myanmar’s membership would strengthen the grouping’s influence. It was also keen to woo Myanmar away from China’s embrace, which had been strengthened by Western sanctions. Besides, Myanmar was relatively undeveloped, was rich in natural resources and offered a potential market for technology and consumer goods.

Up until recently, the decision to join ASEAN seemed to have paid off. Membership had helped successive governments in Myanmar offset China’s influence and resist foreign pressures. It also helped to attract foreign investment and probably encouraged Barack Obama’s policy of “pragmatic engagement”. ASEAN criticism of human rights abuses by Myanmar’s security forces, for example against the Muslim Rohingyas, had been relatively muted.

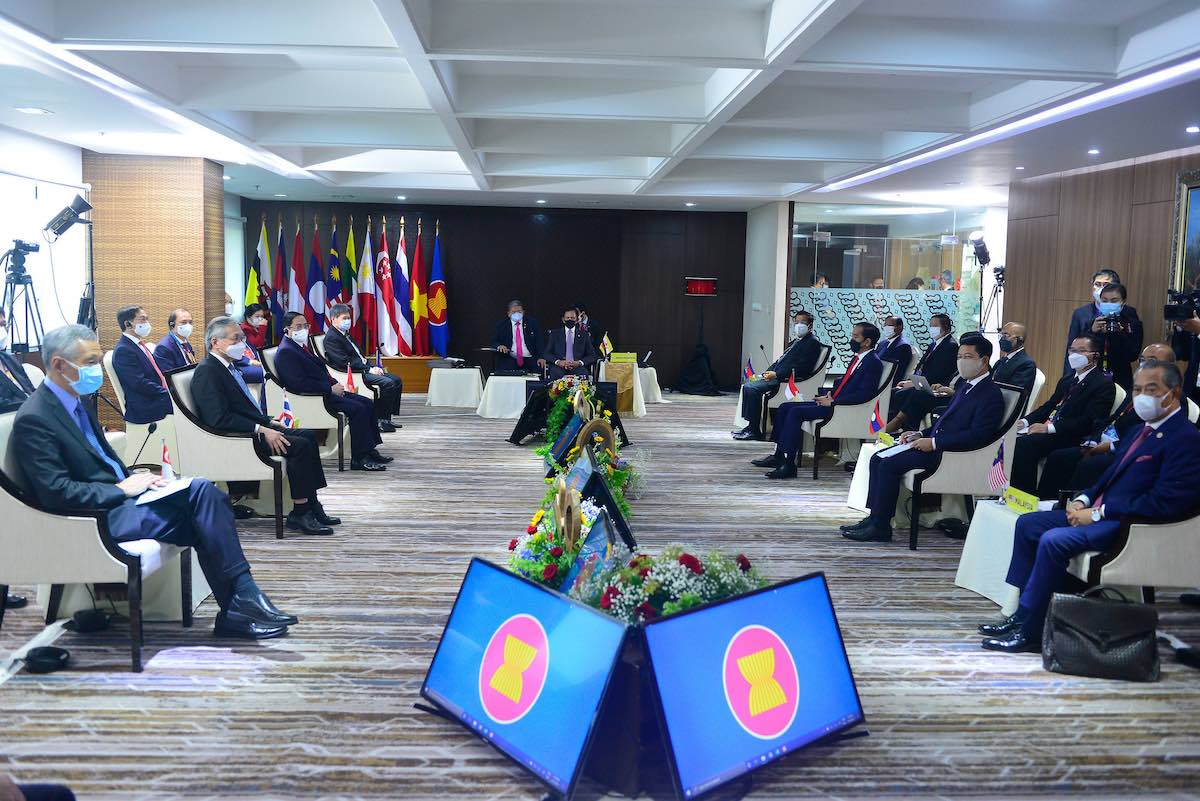

The coup on 1 February shocked ASEAN, which soon met to formulate a response. Junta leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing was invited to attend. However, the resulting “Five Point Consensus” lacked teeth. The junta has since refused permission for the ASEAN envoy agreed upon at that meeting to speak to ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi. This seems to have prompted the decision not to invite Min Aung Hlaing to the ASEAN summits later this month.

According to a statement issued by the ASEAN chairman, “the situation in Myanmar was having an impact on regional security as well as the unity, credibility and centrality of ASEAN as a rules-based organisation”. A “non-political” representative from Myanmar would be permitted to attend the coming summits, but this effectively ruled out anyone of significance from either the junta or the shadow National Unity Government.

Given the membership of ASEAN, which includes few genuine democracies, and the association’s repeated failure to speak up for Myanmar’s oppressed population, the chairman’s statement reeks of double standards. As commentator Bertil Linter has written, it was probably prompted more by ASEAN’s declining influence and fear of popular opinion, than by any real concern for developments in Myanmar.

The junta has accused the association of ignoring the principles enshrined in its founding charter and interfering in Myanmar’s internal affairs. Indeed, some generals believe that ASEAN has deliberately sided with their enemies, foreign and domestic. In these circumstances, it would not be surprising if they considered pulling Myanmar out of ASEAN.

Myanmar has a long record of going it alone. For example, it was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961, but left the grouping in 1979 when it started leaning towards the Eastern bloc. That spirit lives on. The 2008 constitution, which was drafted by a former military regime, specified that Myanmar should pursue an “active, independent and non-aligned foreign policy”. It was an approach embraced by both military and quasi-civilian administrations.

Myanmar’s military mindset has always been difficult to understand, but the generals have always held firmly to the principle that the country must remain independent. They are also convinced that only they know what is best for its survival as a unified, sovereign state. With this in mind, successive military regimes have strongly resisted external pressures, and been determined to go their own way, regardless of the costs, human and otherwise.

As I have argued in a recent study for the Griffith Asia Institute, this pattern has been repeated since the February coup. Public criticism, sanctions, travel bans and arms embargoes have all seemed to roll off the backs of the generals, who appear prepared once again to hunker down in “Fortress Myanmar” and, with the help of friends such as China and Russia, endure whatever history throws at them.

ASEAN membership still offers benefits for Myanmar, which under the previous government became more integrated into international politics and commerce. Also, the junta needs all the friends it can get. However, if the association appears to have turned against it, then it is possible that the generals will come to the conclusion that they can live without it.

Also, the junta knows that, whether or not Myanmar is a member of ASEAN, regional countries will still need to treat and trade with it, if only out of self-interest. Internal developments in Myanmar will still have the potential to affect the regional security environment. There will still be strategic reasons for trying to balance China’s influence in Myanmar.

All these factors may encourage the generals to dig in and threaten Myanmar's withdrawal from the association, if the junta is not recognised by ASEAN as the country's government.