For the first time since the Geneva Agreements of 1954, France has turned its eyes towards what is now termed the Indo-Pacific. The renewal of Paris’s interest in the region not only reflects a desire to tap on the wealth of rising Asia, but also Emmanuel Macron’s desire to restore France’s great power status. Yet in attempting to break into a crowded diplomatic space with diminished geopolitical and economic influence, it is questionable if French attempts to restore its grandeur will prove a sustainable venture.

A strong and successful foreign policy would not only serve Emmanuel Marcon as a welcome diversion to policy failures at home, but also as a powerful rallying symbol to unite a divided nation.

Contemporary French interest in the Indo-Pacific has largely been pursued with the objective of jumpstarting France’s stagnant economy through trade and economic relations. As early as the Nicolas Sarkozy presidency, Paris has sought to tap the increased economic opportunities of Asia by opening up regional markets to French products, especially in the area of arms trade. Macron’s predecessor François Hollande, in particular, sought to develop a more systematic form of engagement with a wider range of regional states, making a record number of visits to Asian nations during his administration.

France itself is technically in the Indo-Pacific. It possesses several overseas territories in the region – 1.5 million French citizens and 90% of France’s maritime Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) are found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans (including those stretching out from New Caledonia, French Polynesia and Réunion Island, among others). Serving as “aircraft carriers” that allow France to project power into the region, these islands feature a strong French military presence consisting of around 8000 troops. Pacific EEZs, moreover, provide France with access to valuable resources such as fishing stocks and hydrocarbons.

Paris has been concerned, however, with China’s growing Indo-Pacific ambitions. Not only does France share the European Union’s concerns with Beijing’s record in trade and human rights, it also sees Beijing’s assertiveness in the South China Sea as a threat to freedom of navigation. Indeed, Macron warned a European Council meeting in March that “the time of European naivete [towards China] is over”, signalling a harder China policy in the near future.

Macron has thus proposed a new strategic alliance with Australia and India during a 2018 speech in Sydney and sought out security ties with Japan in an attempt to check Beijing’s regional ambitions. He has also deployed France’s sole carrier group into the South China Sea to conduct freedom of navigation operations – a move likely seen by Beijing as an attempt to “contain” China’s rise.

Such moves reflects Macron’s attempt to revive former president Charles de Gaulle’s policy of grandeur, which sought to restore France’s status as a great power through an independent foreign policy. Believing that France must be “ambitious in the wider world” and become “a great power again”, Macron has sought to assert European (and by extension, French) strategic autonomy vis-à-vis an increasingly unreliable US while taking leadership on global issues such as climate change.

Echoing de Gaulle’s independent and exceptionalist foreign policy would also help Macron reassert his strongman image to restore the faith of an increasingly disillusioned population in light of low approval ratings and the gilet jaunes protests. A strong and successful foreign policy would not only serve as a welcome diversion to policy failures at home, but also as a powerful rallying symbol to unite a divided nation.

France faces numerous obstacles, however, in its attempts to expand its regional influence, not least being the increasingly crowded Indo-Pacific strategic environment. As the Indo-Pacific grows in economic and strategic importance, great and middle powers such as Russia and South Korea are increasingly vying for regional influence. For a long-absent middle power like France to regain its relevance in this competitive region, it must provide regional states with international public goods (i.e. free trade) or diplomatic largesse (foreign aid) to strengthen its regional leverage and recognition as a great power.

Paris may find it difficult, however, to sustain its Indo-Pacific presence. Not only have years of weak economic growth meant that France experiences weak government finances and low competitiveness, there exists a significant gulf in military capabilities between the French armed forces and that of other regional powers – especially with regards to naval capabilities crucial for maritime power projection. With existing security commitments in Africa (though resources have increasingly been redirected to Asia), one questions if France has the economic and military resources to sustain an Indo-Pacific presence.

While working with the EU could amplify French diplomatic clout, the need for consensus in deciding EU foreign policy may restrict France’s room for manoeuvre vis-à-vis economic diplomacy. The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy – which covers trade and commercial policy – requires ratification from all member states for foreign policy decisions to pass. France is therefore unable to quickly dispense economic largesse such as Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) to developing countries in the region, making it a less attractive regional partner.

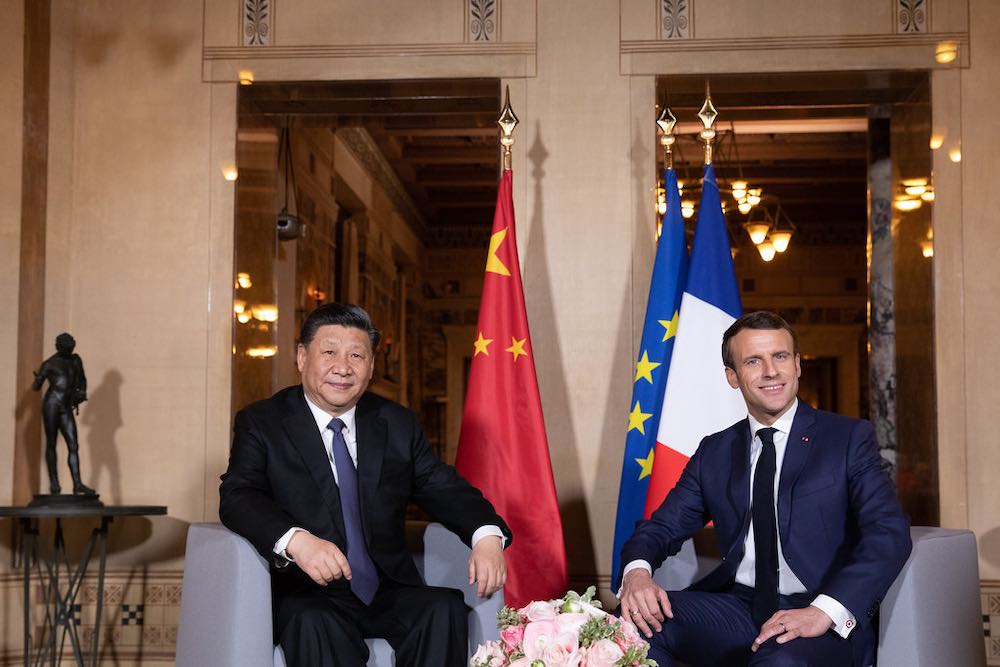

France’s ability to balance China is moreover constrained by the economic imperative of maintaining working ties with Beijing. Macron met China’s President Xi Jinping in Paris where both called for a “sound and stable” and “strong Europe-China partnership”, concluding 15 business deals that included a larger than expected deal on Boeing aircraft. France needs Chinese markets and foreign direct investment to jumpstart its economy; the risk of losing these to Chinese retaliation may constrain France’s ability to balance Beijing.

It is ironic that the policy of grandeur that Macron seeks to emulate was in fact more a sign of weakness than strength – a form of political theatre designed to rescue the pride of a declining power. In spite of Macron’s ambitions, significant structural realities hinder the expansion of French Indo-pacific influence. Whether France still possesses the wherewithal to sustain an Indo-Pacific presence is, therefore, debatable.