In January, the Chinese government released its third white paper on foreign aid, entitled “China’s International Development Cooperation in the New Era”. It is worth taking a closer look at the Chinese-language original, which is more detailed in content than the English-language version, to see what has changed in some aspects of China’s foreign aid program, and what has not. Hopefully the findings can bring a better understanding of the prospects of Chinese aid and its potential impact on the international aid system.

China is the world’s largest emerging donor, and Chinese foreign aid is going to be more instrumental in Chinese external relations. In particular, as the white paper emphasises, the government has used and will continue to use its foreign aid to support the concept of “global community of shared future” and the Belt and Road Initiative. As major components of the “Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy”, these two strategies will guide the Chinese aid program and also make strategic considerations more important factors in aid allocation.

What has changed

China has become increasingly active in supporting policy planning of recipient governments, covering a wide range of sectors, such as national economic development, infrastructure, electricity, customs, taxation, agriculture, environmental protection and water resources. This is a new development. By “exporting” its expertise, China aims to expand its influence in the global South.

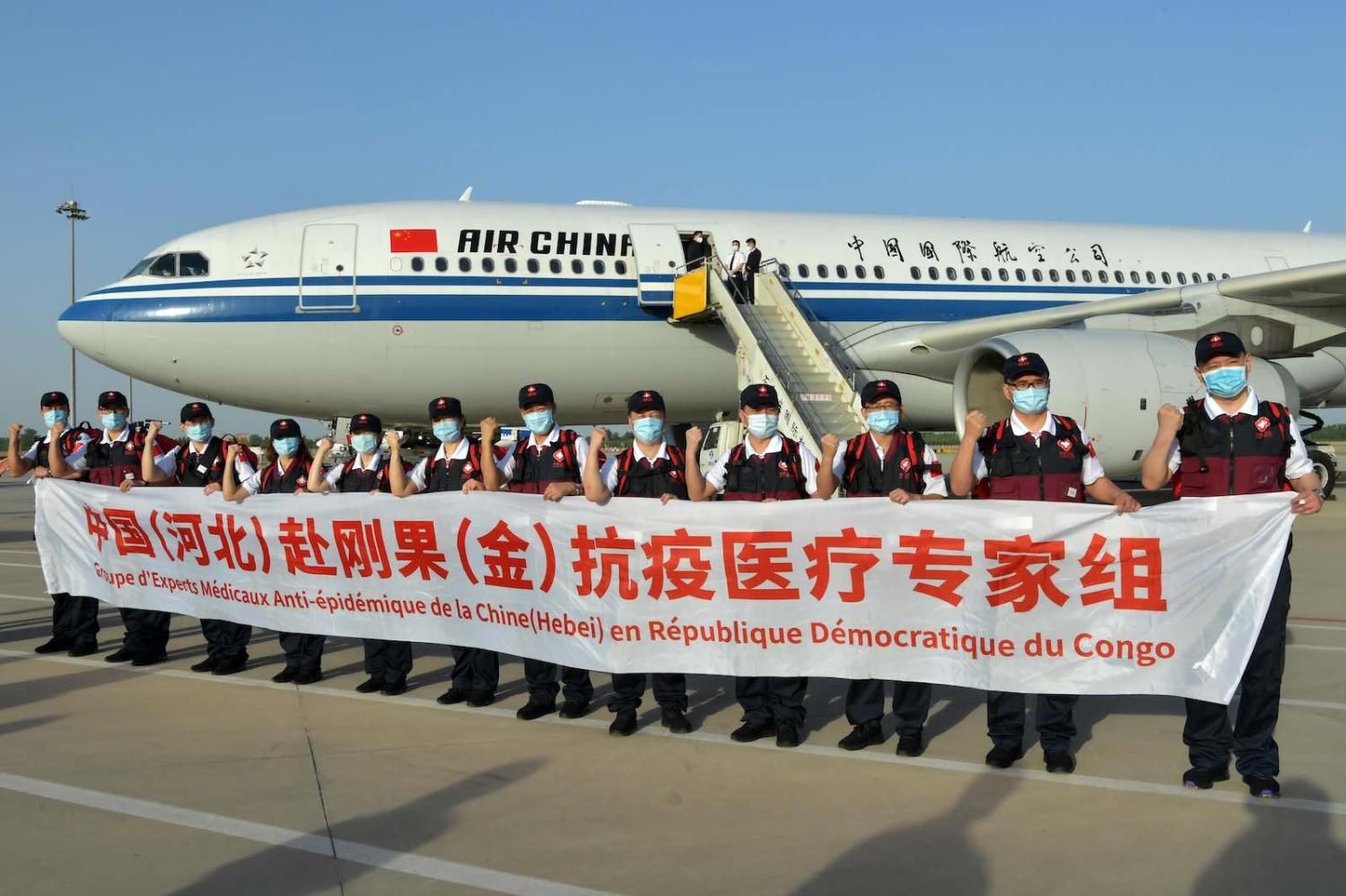

There is also more focus on humanitarian aid, with a whole chapter on the sector reaffirming China’s commitment to supporting countries responding to disasters and public health emergencies, post-disaster reconstruction, disaster prevention and risk reduction. It extols China’s Covid-19 assistance operations overseas as the “most intensive and largest-scale emergency humanitarian assistance mission” in China’s history since 1949.

The white paper pledges to provide US$2 billion to countries most affected by the pandemic over the next two years and supply Covid-19 vaccines, when ready, as public goods. Little wonder that in the near future, Covid-19 diplomacy, with its focus on medical assistance, vaccines and post-crisis recovery, will prevail in China’s foreign aid program.

Support for the World Health Organisation is clearly stated:

The WHO has made a significant contribution to the fight against the pandemic by leading and encouraging global cooperation. To support the WHO is to support global cooperation in the fight against the pandemic and support the effort to save lives.

Throwing its weight behind the WHO is consistent with China’s policy of visibly supporting the UN-centric international system, which China believes serves its best interests.

Another whole chapter is devoted to international exchanges and trilateral cooperation, with the mention of pilot projects with Switzerland, Portugal, the UK, the US, Australia and New Zealand over the period 2013–18. The message is that China is willing to cooperate with traditional donors in the aid sector, but such partnerships must follow certain rules, such as: trilateral aid projects need to “be proposed, agreed and led by recipient countries”; they should be promoted on a gradual basis; and all sides need to focus on mutual respect, trust and learning. It is expected that China will expand trilateral aid experimentation with UN organisations and selected traditional donor states.

What hasn’t changed

The white paper begins with the statement that “China is the largest developing country in the world”. It also emphasises that the South-South cooperation is the “fundamental positioning” (ding wei) of China’s foreign aid program which “falls into the category of South-South cooperation and therefore is essentially different from North-South cooperation”.

These points demonstrate that although China is the world’s largest emerging donor and the second-largest economy, it will continue to cling to its identity as a developing country and a South-South cooperation partner.

Siding with the global South rests on China’s diplomatic and strategic considerations: trust of Western countries is limited due to deep-rooted suspicions, China puts more trust in the global South than the West, and developing countries can provide China valuable support (diplomatically and strategically) in times of need, such as the current Covid-19 crisis.

Not interfering in recipient countries’ internal affairs, not attaching political strings to its foreign aid,and respecting the development paths chosen by recipient countries – these tenets are entrenched in Chinese aid.

The developing-country identity can also help China fend off pressure from traditional donors to provide more aid. As the white paper says, China “will continue to shoulder the international responsibilities commensurate with its development level and capacity”.

Furthermore, emphasising that South-South cooperation is a supplement to North-South cooperation, and not a replacement to it, provides more ammunition for China to resist pressure from traditional donors. And it assures traditional donors that China is not aiming to create a parallel international aid system.

Not interfering in recipient countries’ internal affairs, not attaching political strings to its foreign aid and respecting the development paths chosen by recipient countries – these tenets are entrenched in Chinese aid, and reiterating them in the white paper suggests that Beijing has been satisfied with these basic principles. As such, China can be expected to continue to circumvent “sensitive” issues such as democracy and good governance in its aid program.

Similar to the first two white papers on foreign aid released in 2011 and 2014, the 2021 white paper includes debt relief in its list of achievements. What remains unchanged is that debt relief has targeted interest-free loans, rather than concessional loans. For example, over the period 2013–18, China wrote off 98 interest-free loans owed by recipient countries, totalling RMB4.18 billion (US$640 million). As concessional loans (and commercial loans) comprise the majority of debts in recipient countries, loans will remain an outstanding concern.

The Chinese government has realised the gravity of the debt issue. The white paper emphasises that China and recipient countries should rely on bilateral consultations to solve the debt problem. Therefore, more such consultations can be expected in the future. Past experience suggests that in the case of debts related to concessional loans, repayment extension is more likely than forgiveness.