Mongolia, sandwiched as it is between China and Russia, the world’s two most powerful authoritarian states, is unlucky. Its rich solar and wind potential may prove to be a curse, not a blessing, as Beijing might be tempted to infringe on Mongolian sovereignty.

Mongolia will, over time, become a much more sensitive issue in Sino-Russian relations.

The numbers show why. Mongolia’s renewable resources are – potentially – transformative for Northeast Asian energy. The Asian Development Bank estimates renewables-rich Mongolia has the potential to generate 5,457 terawatt-hours of clean electricity via wind and solar electricity, or about 63 per cent of China’s total electricity generation in 2022. Mongolia also seems like a natural destination for Chinese solar exports, which are projected to exceed China’s domestic demand by more than 500 per cent by 2030.

If Mongolia exports even a tenth of its renewables potential, the implications for Chinese energy will be immense. Mongolian-generated electricity from renewables could displace or even replace Russian energy exports to China, including from the long-planned Power of Siberia 2 natural gas pipeline. Beijing is already taking initial steps to develop renewables in climatologically-similar regions adjoining Mongolia.

China’s policy towards Mongolian renewables development will have significant implications for its relationship with Russia. Beijing’s economic footprint in Mongolia easily outpaces Moscow’s. China already accounts for the overwhelming majority of Mongolia’s exports, while bilateral trade is rising amid a new cross-border rail linkage.

It is difficult to overstate Beijing’s ability to dictate political and security terms in its landlocked neighbour. The power gap between China and Mongolia is vast. China’s population and GDP are, respectively, 408 and 1,075 times larger than Mongolia’s; Beijing’s claimed military expenditures are nearly 3,000 times greater than its neighbour’s.

To date, two factors have constrained Chinese interventions in Mongolia: a lack of material benefit, and Beijing’s fear of upsetting ties with Moscow. Conditions are changing.

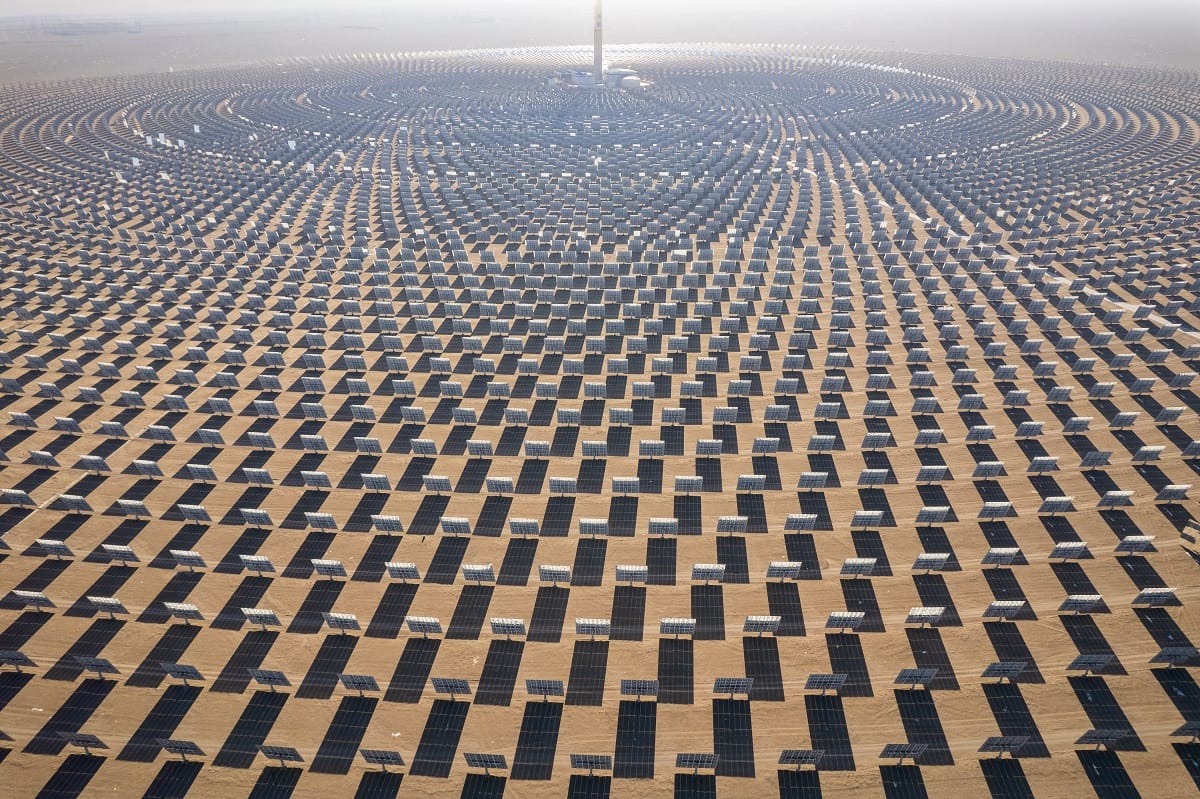

Amid the improving techno-economics of solar, wind and batteries, China is building renewables in its portion of the Gobi Desert, including a US$12 billion solar project for 13 Gigawatts (GW) of solar capacity; it ultimately aims to build 450 GW in arid regions. Since the Gobi extends across both China and Mongolia, the constraint to renewables construction in Mongolia is ultimately political, not technical. If trial projects on its side of the Gobi prove successful, China may seek to deploy solar, wind, batteries, and transmission lines across the border.

While Beijing has trodden lightly in Mongolia in the post-Cold War period to placate Moscow, its posture may be shifting. In May 2021, Mongolia publicly arrested two of its intelligence officers, reportedly for spying for Russian security services. Chinese security services, with one eye on Beijing’s long-term energy interests, may have nudged their Mongolian counterparts to disrupt Russian networks. Mongolian and Chinese security services also cooperated in Ulaanbaatar’s arrest of a Mongolian-language anti-China activist who fled China’s province of Inner Mongolia.

Transforming Mongolia into a renewables exporter won’t be easy: dramatic infrastructure overhauls to site enormous wind turbines and solar farms and connect them to Chinese demand centres will require years and massive injections of capital and labour.

The politics of Mongolian renewables development would also be fraught. Beijing will likely seek to absorb Mongolia’s renewables potential peacefully, without provoking a sanctions response from the West, but even a non-coercive buildout of renewables would see tens of thousands of Chinese workers enter a tiny country.

China could soon make major moves in Mongolia, despite these constraints.

Given its reluctance to upset political ties with Moscow or its economic relationships with Washington and Brussels, Beijing will likely move slowly in Mongolia, attempt to use non-coercive instruments whenever possible, and downplay any threats to Russia’s energy exports. Beijing’s posture could change, however, as the techno-economics of Mongolia’s wind and solar potential become more alluring. Indeed, the recent China–Mongolia rail network expansion could be repurposed for mass shipment of solar panels and may be an initial sign of Beijing’s interest in Mongolian renewables.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has utterly renounced the West, ensuring Russia has become China’s junior partner. This equilibrium is unstable, however, as Russia’s declining economic and military power slowly renders it less useful to China. Over the long term, Mongolian renewables could further reduce Russia’s value in Chinese energy security. Russia and China are close today, but Moscow may be about to learn a hard lesson.

This article represents the author’s own personal opinion.